BY SHILLA COLLECTIVE

شلة

yellow the manifesto

SHILLA ART COLLECTIVE, MANIFSTO (0) 26/7/2025

In the heart of Nairobi, beneath an unnamed sky, a group of Sudanese artists found themselves exiled by the war of April 15th. Out of the ashes of that catastrophe, “Shilla” emerged — a form compelled into existence, nourished by artistic urgency, and grown into the seed of a new Sudanese artistic experiment: one that is free, curious, and collaborative.

“Shilla” is not a passing formation; it is a fervent and sincere attempt to reimagine modes of artistic organization under exceptional circumstances. It is an act of resistance, an open house, and a shared space animated by dialogue, driven by the thrill of discovery, and attuned to the boundless possibilities of art.

On Context

In the context of exile, far from Khartoum, and within an unfamiliar artistic landscape, “Shilla” found itself confronted with an unknown space — one that stirred its instincts and compelled it to question itself and its creative process, through openness to the experiences and approaches of others in art and cultural work.

Nairobi’s artistic scene, despite its diversity, is marked by clear organizational structures rooted in collaborative practice — especially through what is globally known as “art collectives.”

Yet when this term is translated into Arabic, it is often rendered as “tajammu‘ fanī(تجمع فني )” (art group) — a descriptive phrase that fails to capture the structural, functional, and relational weight of the original concept. “Tajammu‘” merely implies the numerical presence of three or more individuals, without reflecting the nature of the relationships between them, their organizational fabric, or their shared objectives.

It is also a static term — devoid of the connotations of action, historical accumulation, and the dynamic qualities that are meant to define the essence of an art collective.

One might suggest instead the term “ta‘āwuniyya fanīya)” (artistic cooperative), which aligns more closely with the functional reality of the concept. It suggests a productive relationship, with temporal continuity and mutual investment in a long-term artistic endeavor.

However, even this term remains burdened by economic overtones — particularly in the Sudanese context, where “cooperatives” have historically been understood as materially driven entities. In this way, the term loses its ability to express the emotional and human dimensions that distinguish an art collective, and fails to capture the social and cultural ties that bind its members together.

It is out of this semantic gap that the term “Shilla” is proposed — a cultural and artistic alternative that carries emotional and conceptual weight. Linguistically, the word refers to a circle of close friends, which immediately affirms the affective and social nature of this artistic formation.

“Shilla” is not merely a numerical label; it is a linguistic and philosophical proposal that reflects the quality of relational ties between members.

In everyday usage, “Shilla” describes a group of emotionally bonded individuals whose connection is not based solely on a shared goal or fixed project, but rather on a meshwork of cultural, artistic, and intellectual relationships — nourished by a collective desire for change or for exploring new possibilities.

The selection of this word reflects not only the actual conditions that gave rise to the group, but also a vision of artistic practice as an extension of human relation — as something rooted in trust, mutual care, and unconditional belonging.

Metaphorically, the word evokes the image of “a bundle of entangled threads” — a symbol of interweaving, integration, and cohesion, achieved despite difference and variation among its members.

Within Sudanese cultural memory, “Shilla” also bears a strong emotional resonance: it expresses solidarity, affection, and a sense of belonging — all of which form the emotional and social infrastructure of this collaborative project.

Thus, “Shilla” is not a linguistic workaround or poetic evasion of failed translation. It is both a linguistic and existential critique, a means by which the founding group seeks to carve out a space that bears their voice, memory, and form — without severing ties with global artistic practices.

The term resists pre-packaged definitions and attempts instead to generate a concept imbued with poetic, social, and historical charge.

At the same time, “Shilla” serves as a platform for collective artistic production. It does not negate the individual experience, but reframes it within a horizontal network of relations — grounded in dialogue, curiosity, and shared making.

On Collaboration

Organized collaboration has never been a foreign concept to Sudanese public life; rather, it has long been a cornerstone of resistance — politically, socially, and culturally — against colonialism and oppressive regimes.

It is this deeply rooted spirit of cooperation that animates “Shilla” from within. Collaboration, for Shilla, is not a fleeting organizational choice but a continuation of a long historical trajectory of popular action and cultural resistance.

Sudan’s cultural history is dense with artistic and intellectual movements grounded in collective labor: from artists’ unions, to literary and visual art circles, to contemporary grassroots initiatives.“Shilla,” growing out of this lineage, does not seek to break from the past. Instead, it builds upon it — reinterpreting it within a contemporary context, a new exile, and among new comrades and companions.

Nairobi’s artistic landscape, with its diversity and cooperative ethos, has reawakened in Shilla a deep conviction: that collaborative work is not a circumstantial tool, but a necessary condition for the continuity and evolution of artistic creation — especially in a time where political repression coincides with cultural stagnation, and the need for art becomes more vital than ever.

On Isolation

At its core, artistic work is bound to the individuality of the artist — it is they who dream, who judge, who shape the nuances of their human experience into a form of artistic expression.

Yet modern Sudanese artistic practice has long been marked — due to complex historical, political, and cultural forces — by an entrenched individualism that has diminished the collaborative dimension of the artistic process.

This individualism has led to social isolation and institutional marginalization of the artist, rendering the artistic process confined to the self, closed off to the individual experience as the sole path of production.

Such individualism was not merely a rejection of the external world, but often a reaction to a reality in which the support structures of art had deteriorated: exhibition spaces, critical institutions, traditions of artistic dialogue.

In this context, individualism ceased to be a free choice and became instead a coercive condition of production.

Still, “Shilla” does not deny the value of the artist’s individual experience. Rather, it insists on recognizing and deepening that experience — not through withdrawal, but through sustained critical dialogue.

Art does not exist in isolation from its context. The artistic self does not arise in a vacuum, but is refined through interaction with others and through the questions posed by the work itself.

“Shilla” views artistic production as a dialogical path — one that begins from the self and returns to it, mediated by cycles of interaction, discussion, and reflection.

In this way, the individuality of the artist is not threatened but enriched — illuminated from multiple angles through shared looking, mutual interpretation, and artistic exchange.

On Practice

Once the foundational concepts of Shilla’s vision are established, it becomes essential that this vision be reflected in artistic practice itself.

This cooperative does not view the creative process as an isolated act, but as an organic extension of human experience — one that cannot be fulfilled in solitude, nor produced outside relationships of dialogue and exchange.

From this perspective, artistic practice within Shilla is shaped by guiding principles rooted in the artist’s subjective experience and cultural-emotional commitments — producing works that express their existence.

Yet this expression is not concluded with the production of the artwork; rather, it opens into conversations and dialogues that interrogate the work, reframe its meaning, and shift it from a personal space into a collective social and cultural impact.

Shilla sees the creative process as one that does not end at the studio’s threshold. It continues as a reciprocal relationship between the artist and others.

Within this extension, the role of artistic coordination emerges as a fundamental component of the creative process — not as a detached technical function, but as part of a collaborative fabric managed by the group in a spirit of participation.

Although artistic coordination may appear, especially in the Sudanese context, as a separate stage — due to long-standing institutional marginalization — this separation has weakened the social and productive dimensions of art, diminishing its cultural impact and rendering artistic work, in many cases, a closed-off experience.

Shilla rejects this separation, instead reclaiming coordination as a democratic and collaborative practice, inseparable from the broader act of creation.

In doing so, it resists rigid structural divisions and reimagines artistic production as an ongoing dialogue between the individuality of the artist and the surrounding cultural and social environment.

Shilla regards this shared practice as a deeply emotional act — rooted in human collaboration, openness, and the desire to form a collective artistic experience that does not erase individual differences, but illuminates them through exchange, interaction, and dialogue.

In this way, artistic production is realized as a holistic relationship between human beings, society, memory, and the desire to say something honest, shared, and free.

Members

Amani Azhari

Heraa hassan

Hozaifa Elsiddig

Mohamed Wraag

Sannad Shreef

Waleed Mohammed

Yathrip Hassan

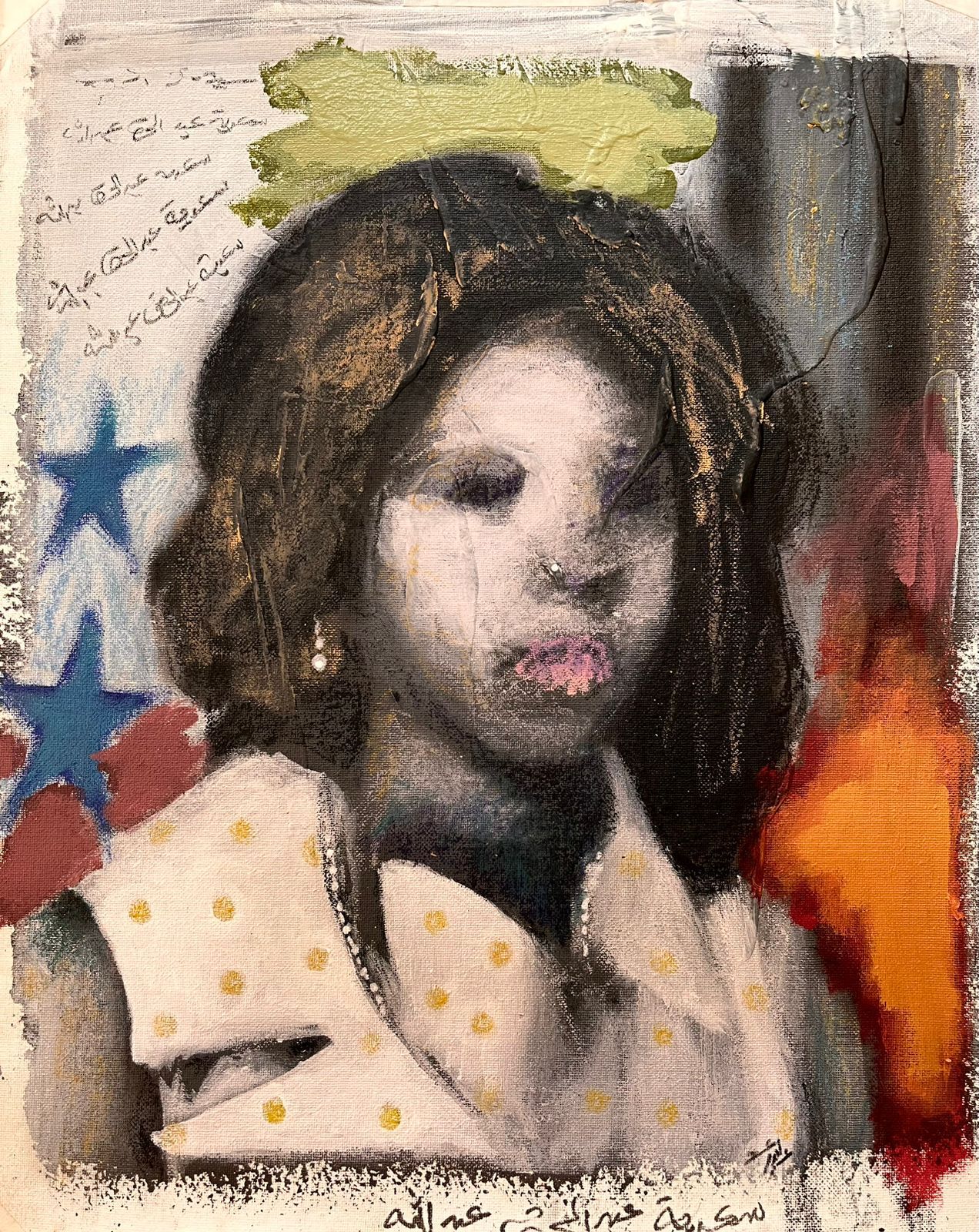

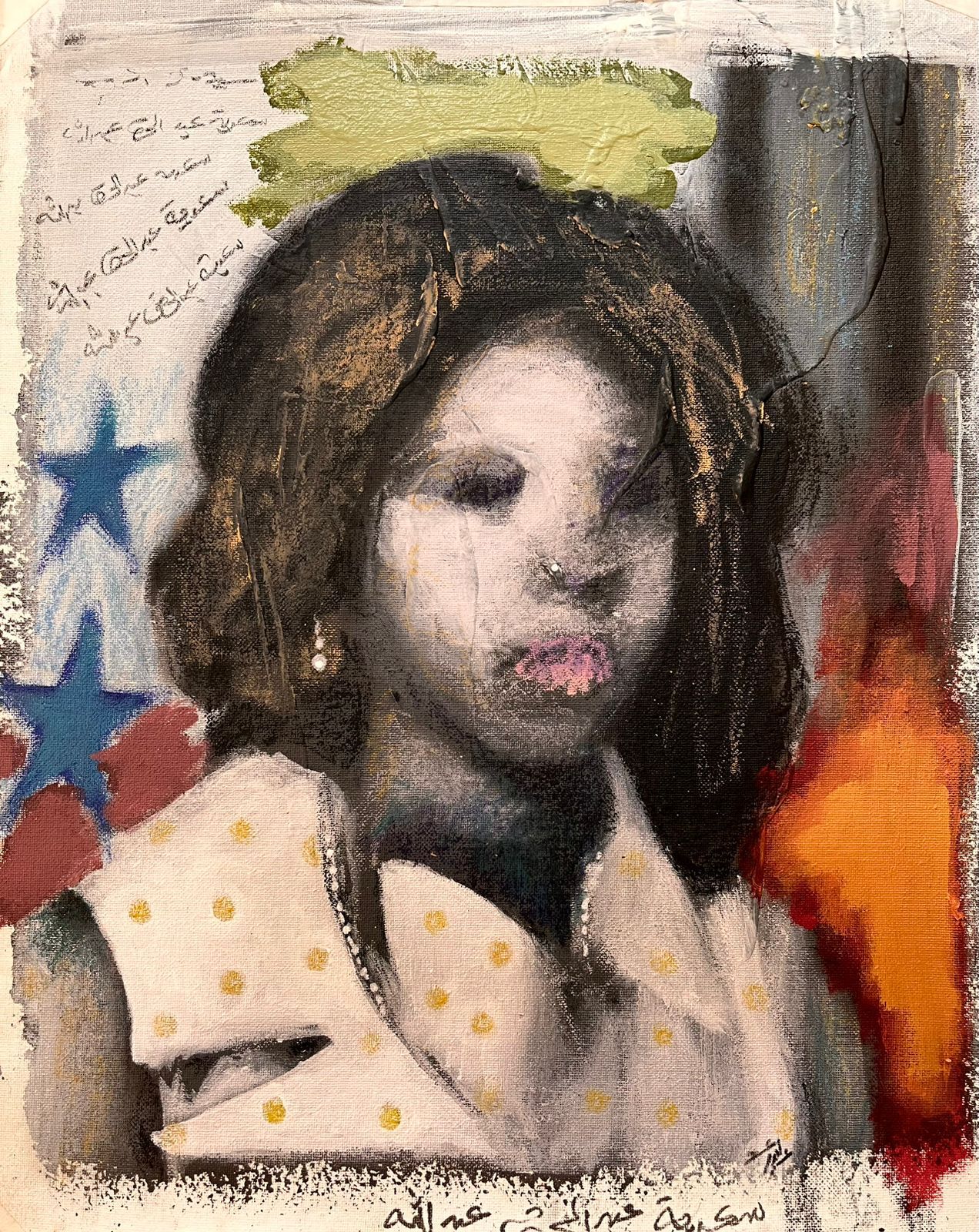

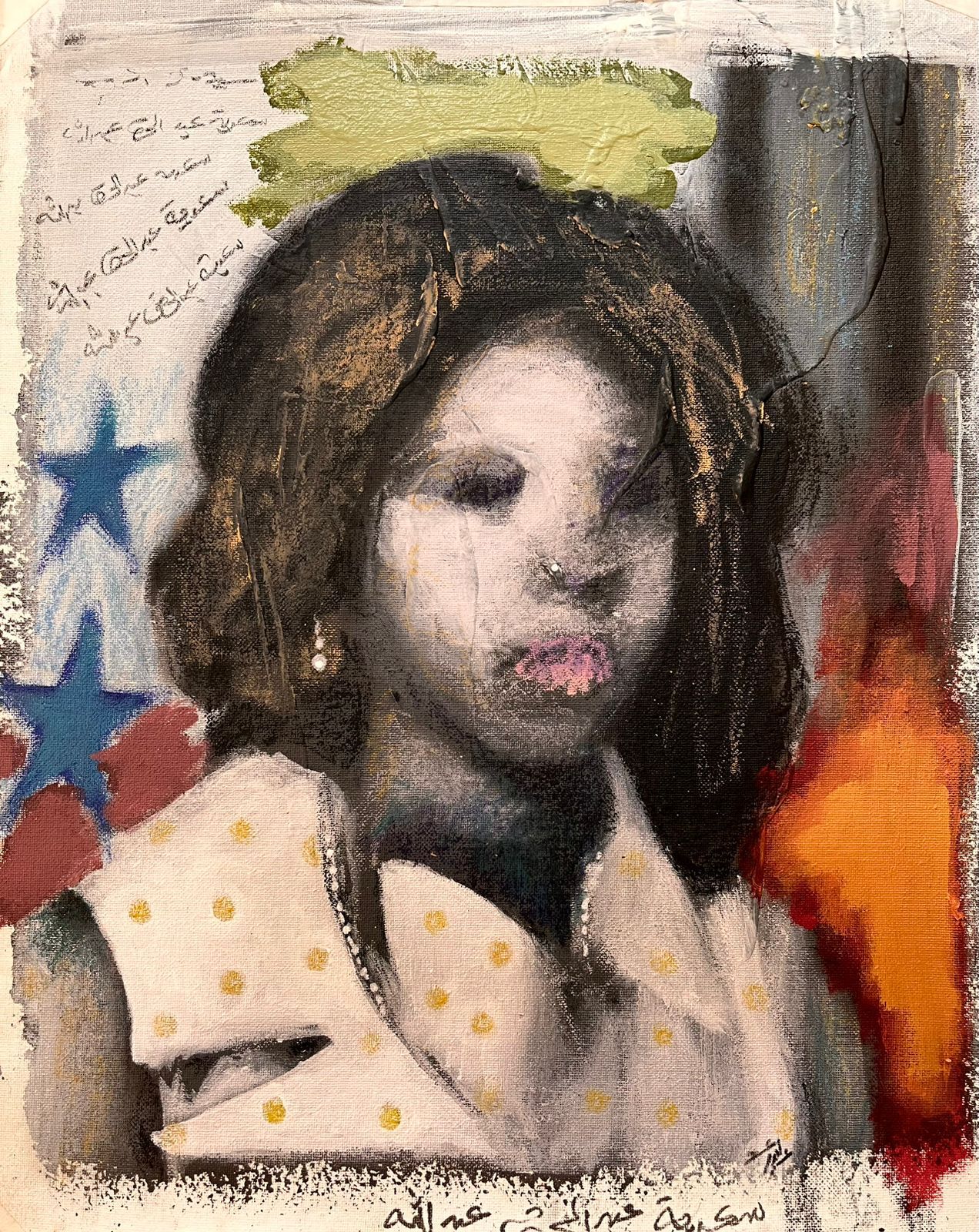

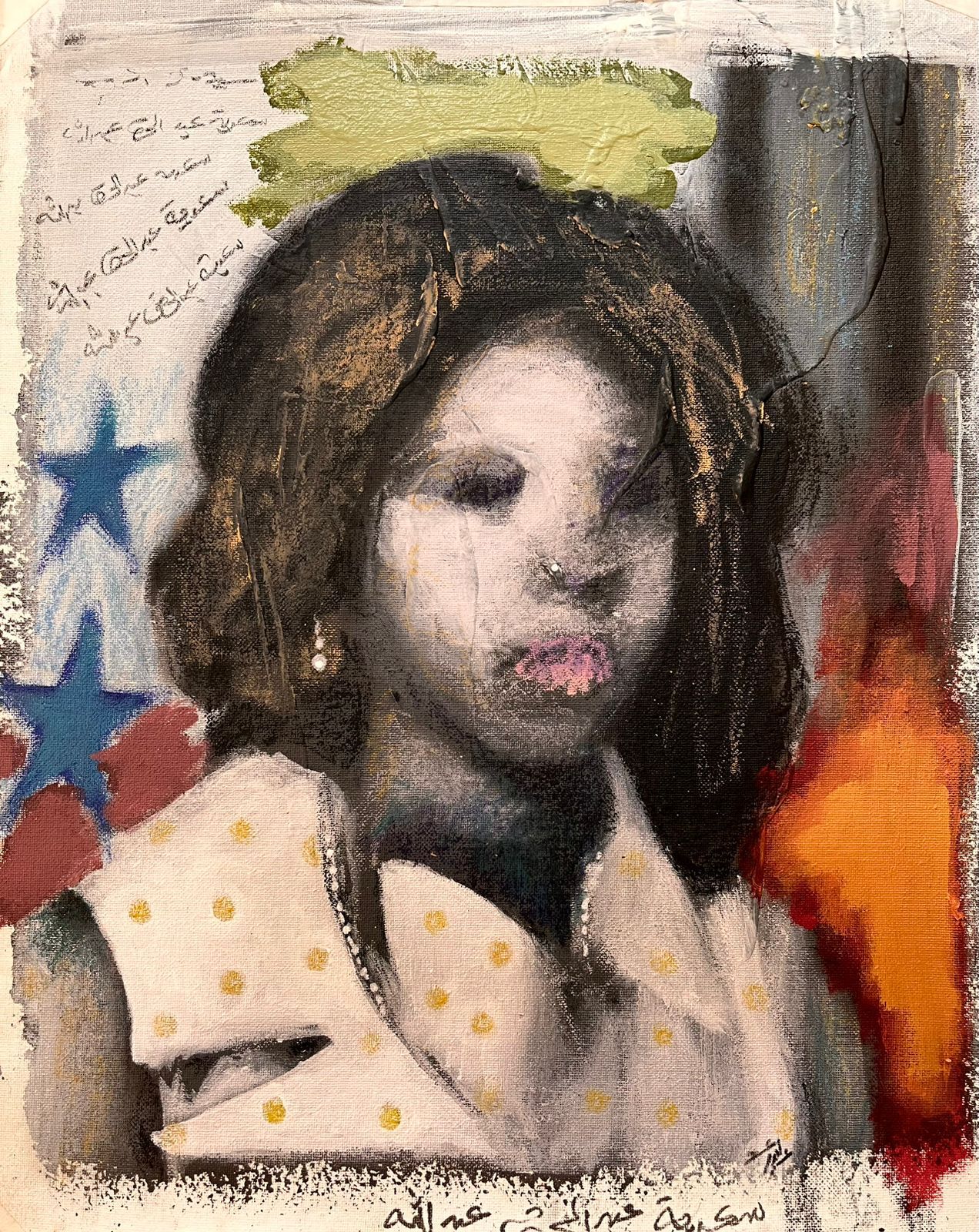

Images 1-3 by Amani Azhari, part of Healing Sessions series.

Artist Statement: Historically, women have gathered in intimate spaces that served as sanctuaries for healing and support—safe environments where they could share openly without fear of judgment or criticism. These gatherings often focused on the deeply personal and painful realities of sexual violence and other forms of abuse—experiences that were frequently endured in silence.

For many young women, understanding their identity and worth is a journey that takes time, patience, and introspection. Untangling personal narratives from the misconceptions imposed by society is not always easy. Recognizing where external narratives end and where our authentic stories begin can be both challenging and courageous—but it is an essential step toward living truthfully and freely. This is where the seed of healing is planted.

Every woman who heals herself contributes not only to her own well-being but also to the healing of the women who came before her and those who will come after. Womanhood is deeply rooted in the power of reception, reflection, and renewal. The more a woman becomes aware of the psychological impact of her environment, the better equipped she is to break cycles of trauma and prevent them from passing on to future generations.

The traumas we experience shape not only our inner world but also our outward expressions. When we begin to heal, it shows in our presence—our features become softer, more vibrant, and more at ease, reflecting the peace we cultivate within.

These healing sessions have continually inspired Amani in her work. She is deeply moved by the authenticity that arises when women are invited to sit together, express themselves freely, and draw strength from one another. It is in these moments of shared vulnerability and resilience that women begin to transform. Amani believes that true healing starts from within, and once internal harmony is restored, life itself begins to change in profound ways.

These gatherings often take place in the home—a space symbolizing comfort, calm, and cherished memories—making it the ideal setting for healing to begin.

Images 4-6 by Waleed Mohammed

6. I just got my hair done!

Medium: acrylic and pastel on canvas

115x115 cm, 2025

7. Ahmed Osman

Medium: acrylic and wax crayons on canvas

85 x 85 cm, 2025

8. Forever grateful to have stumbled upon you xx

Medium: acrylic and wax crayons on canvas

35 x 40 cm, 2025

Images 7-9 by Abdulla Basher

Artist Statement

I draw inspiration from the simple things around me. A movement or a gesture can hold everything. Within my artistic practice, I work with freedom—abstraction and colour give me this space. I layer, add, and slash until I reach the image that lies within me, waiting to be revealed.

شلة

yellow the manifesto

SHILLA ART COLLECTIVE, MANIFSTO (0) 26/7/2025

In the heart of Nairobi, beneath an unnamed sky, a group of Sudanese artists found themselves exiled by the war of April 15th. Out of the ashes of that catastrophe, “Shilla” emerged — a form compelled into existence, nourished by artistic urgency, and grown into the seed of a new Sudanese artistic experiment: one that is free, curious, and collaborative.

“Shilla” is not a passing formation; it is a fervent and sincere attempt to reimagine modes of artistic organization under exceptional circumstances. It is an act of resistance, an open house, and a shared space animated by dialogue, driven by the thrill of discovery, and attuned to the boundless possibilities of art.

On Context

In the context of exile, far from Khartoum, and within an unfamiliar artistic landscape, “Shilla” found itself confronted with an unknown space — one that stirred its instincts and compelled it to question itself and its creative process, through openness to the experiences and approaches of others in art and cultural work.

Nairobi’s artistic scene, despite its diversity, is marked by clear organizational structures rooted in collaborative practice — especially through what is globally known as “art collectives.”

Yet when this term is translated into Arabic, it is often rendered as “tajammu‘ fanī(تجمع فني )” (art group) — a descriptive phrase that fails to capture the structural, functional, and relational weight of the original concept. “Tajammu‘” merely implies the numerical presence of three or more individuals, without reflecting the nature of the relationships between them, their organizational fabric, or their shared objectives.

It is also a static term — devoid of the connotations of action, historical accumulation, and the dynamic qualities that are meant to define the essence of an art collective.

One might suggest instead the term “ta‘āwuniyya fanīya)” (artistic cooperative), which aligns more closely with the functional reality of the concept. It suggests a productive relationship, with temporal continuity and mutual investment in a long-term artistic endeavor.

However, even this term remains burdened by economic overtones — particularly in the Sudanese context, where “cooperatives” have historically been understood as materially driven entities. In this way, the term loses its ability to express the emotional and human dimensions that distinguish an art collective, and fails to capture the social and cultural ties that bind its members together.

It is out of this semantic gap that the term “Shilla” is proposed — a cultural and artistic alternative that carries emotional and conceptual weight. Linguistically, the word refers to a circle of close friends, which immediately affirms the affective and social nature of this artistic formation.

“Shilla” is not merely a numerical label; it is a linguistic and philosophical proposal that reflects the quality of relational ties between members.

In everyday usage, “Shilla” describes a group of emotionally bonded individuals whose connection is not based solely on a shared goal or fixed project, but rather on a meshwork of cultural, artistic, and intellectual relationships — nourished by a collective desire for change or for exploring new possibilities.

The selection of this word reflects not only the actual conditions that gave rise to the group, but also a vision of artistic practice as an extension of human relation — as something rooted in trust, mutual care, and unconditional belonging.

Metaphorically, the word evokes the image of “a bundle of entangled threads” — a symbol of interweaving, integration, and cohesion, achieved despite difference and variation among its members.

Within Sudanese cultural memory, “Shilla” also bears a strong emotional resonance: it expresses solidarity, affection, and a sense of belonging — all of which form the emotional and social infrastructure of this collaborative project.

Thus, “Shilla” is not a linguistic workaround or poetic evasion of failed translation. It is both a linguistic and existential critique, a means by which the founding group seeks to carve out a space that bears their voice, memory, and form — without severing ties with global artistic practices.

The term resists pre-packaged definitions and attempts instead to generate a concept imbued with poetic, social, and historical charge.

At the same time, “Shilla” serves as a platform for collective artistic production. It does not negate the individual experience, but reframes it within a horizontal network of relations — grounded in dialogue, curiosity, and shared making.

On Collaboration

Organized collaboration has never been a foreign concept to Sudanese public life; rather, it has long been a cornerstone of resistance — politically, socially, and culturally — against colonialism and oppressive regimes.

It is this deeply rooted spirit of cooperation that animates “Shilla” from within. Collaboration, for Shilla, is not a fleeting organizational choice but a continuation of a long historical trajectory of popular action and cultural resistance.

Sudan’s cultural history is dense with artistic and intellectual movements grounded in collective labor: from artists’ unions, to literary and visual art circles, to contemporary grassroots initiatives.“Shilla,” growing out of this lineage, does not seek to break from the past. Instead, it builds upon it — reinterpreting it within a contemporary context, a new exile, and among new comrades and companions.

Nairobi’s artistic landscape, with its diversity and cooperative ethos, has reawakened in Shilla a deep conviction: that collaborative work is not a circumstantial tool, but a necessary condition for the continuity and evolution of artistic creation — especially in a time where political repression coincides with cultural stagnation, and the need for art becomes more vital than ever.

On Isolation

At its core, artistic work is bound to the individuality of the artist — it is they who dream, who judge, who shape the nuances of their human experience into a form of artistic expression.

Yet modern Sudanese artistic practice has long been marked — due to complex historical, political, and cultural forces — by an entrenched individualism that has diminished the collaborative dimension of the artistic process.

This individualism has led to social isolation and institutional marginalization of the artist, rendering the artistic process confined to the self, closed off to the individual experience as the sole path of production.

Such individualism was not merely a rejection of the external world, but often a reaction to a reality in which the support structures of art had deteriorated: exhibition spaces, critical institutions, traditions of artistic dialogue.

In this context, individualism ceased to be a free choice and became instead a coercive condition of production.

Still, “Shilla” does not deny the value of the artist’s individual experience. Rather, it insists on recognizing and deepening that experience — not through withdrawal, but through sustained critical dialogue.

Art does not exist in isolation from its context. The artistic self does not arise in a vacuum, but is refined through interaction with others and through the questions posed by the work itself.

“Shilla” views artistic production as a dialogical path — one that begins from the self and returns to it, mediated by cycles of interaction, discussion, and reflection.

In this way, the individuality of the artist is not threatened but enriched — illuminated from multiple angles through shared looking, mutual interpretation, and artistic exchange.

On Practice

Once the foundational concepts of Shilla’s vision are established, it becomes essential that this vision be reflected in artistic practice itself.

This cooperative does not view the creative process as an isolated act, but as an organic extension of human experience — one that cannot be fulfilled in solitude, nor produced outside relationships of dialogue and exchange.

From this perspective, artistic practice within Shilla is shaped by guiding principles rooted in the artist’s subjective experience and cultural-emotional commitments — producing works that express their existence.

Yet this expression is not concluded with the production of the artwork; rather, it opens into conversations and dialogues that interrogate the work, reframe its meaning, and shift it from a personal space into a collective social and cultural impact.

Shilla sees the creative process as one that does not end at the studio’s threshold. It continues as a reciprocal relationship between the artist and others.

Within this extension, the role of artistic coordination emerges as a fundamental component of the creative process — not as a detached technical function, but as part of a collaborative fabric managed by the group in a spirit of participation.

Although artistic coordination may appear, especially in the Sudanese context, as a separate stage — due to long-standing institutional marginalization — this separation has weakened the social and productive dimensions of art, diminishing its cultural impact and rendering artistic work, in many cases, a closed-off experience.

Shilla rejects this separation, instead reclaiming coordination as a democratic and collaborative practice, inseparable from the broader act of creation.

In doing so, it resists rigid structural divisions and reimagines artistic production as an ongoing dialogue between the individuality of the artist and the surrounding cultural and social environment.

Shilla regards this shared practice as a deeply emotional act — rooted in human collaboration, openness, and the desire to form a collective artistic experience that does not erase individual differences, but illuminates them through exchange, interaction, and dialogue.

In this way, artistic production is realized as a holistic relationship between human beings, society, memory, and the desire to say something honest, shared, and free.

Members

Amani Azhari

Heraa hassan

Hozaifa Elsiddig

Mohamed Wraag

Sannad Shreef

Waleed Mohammed

Yathrip Hassan

Images 1-3 by Amani Azhari, part of Healing Sessions series.

Artist Statement: Historically, women have gathered in intimate spaces that served as sanctuaries for healing and support—safe environments where they could share openly without fear of judgment or criticism. These gatherings often focused on the deeply personal and painful realities of sexual violence and other forms of abuse—experiences that were frequently endured in silence.

For many young women, understanding their identity and worth is a journey that takes time, patience, and introspection. Untangling personal narratives from the misconceptions imposed by society is not always easy. Recognizing where external narratives end and where our authentic stories begin can be both challenging and courageous—but it is an essential step toward living truthfully and freely. This is where the seed of healing is planted.

Every woman who heals herself contributes not only to her own well-being but also to the healing of the women who came before her and those who will come after. Womanhood is deeply rooted in the power of reception, reflection, and renewal. The more a woman becomes aware of the psychological impact of her environment, the better equipped she is to break cycles of trauma and prevent them from passing on to future generations.

The traumas we experience shape not only our inner world but also our outward expressions. When we begin to heal, it shows in our presence—our features become softer, more vibrant, and more at ease, reflecting the peace we cultivate within.

These healing sessions have continually inspired Amani in her work. She is deeply moved by the authenticity that arises when women are invited to sit together, express themselves freely, and draw strength from one another. It is in these moments of shared vulnerability and resilience that women begin to transform. Amani believes that true healing starts from within, and once internal harmony is restored, life itself begins to change in profound ways.

These gatherings often take place in the home—a space symbolizing comfort, calm, and cherished memories—making it the ideal setting for healing to begin.

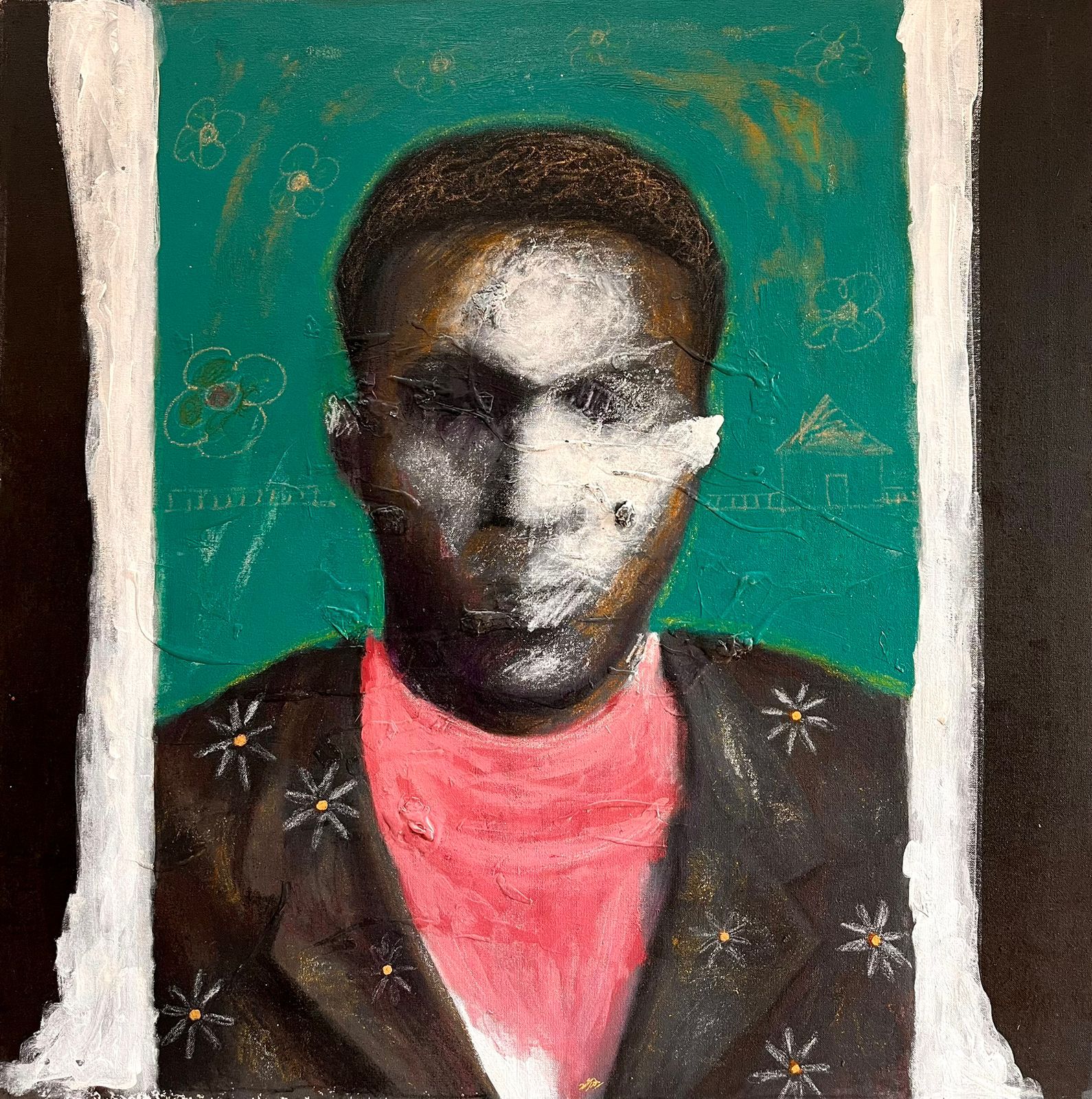

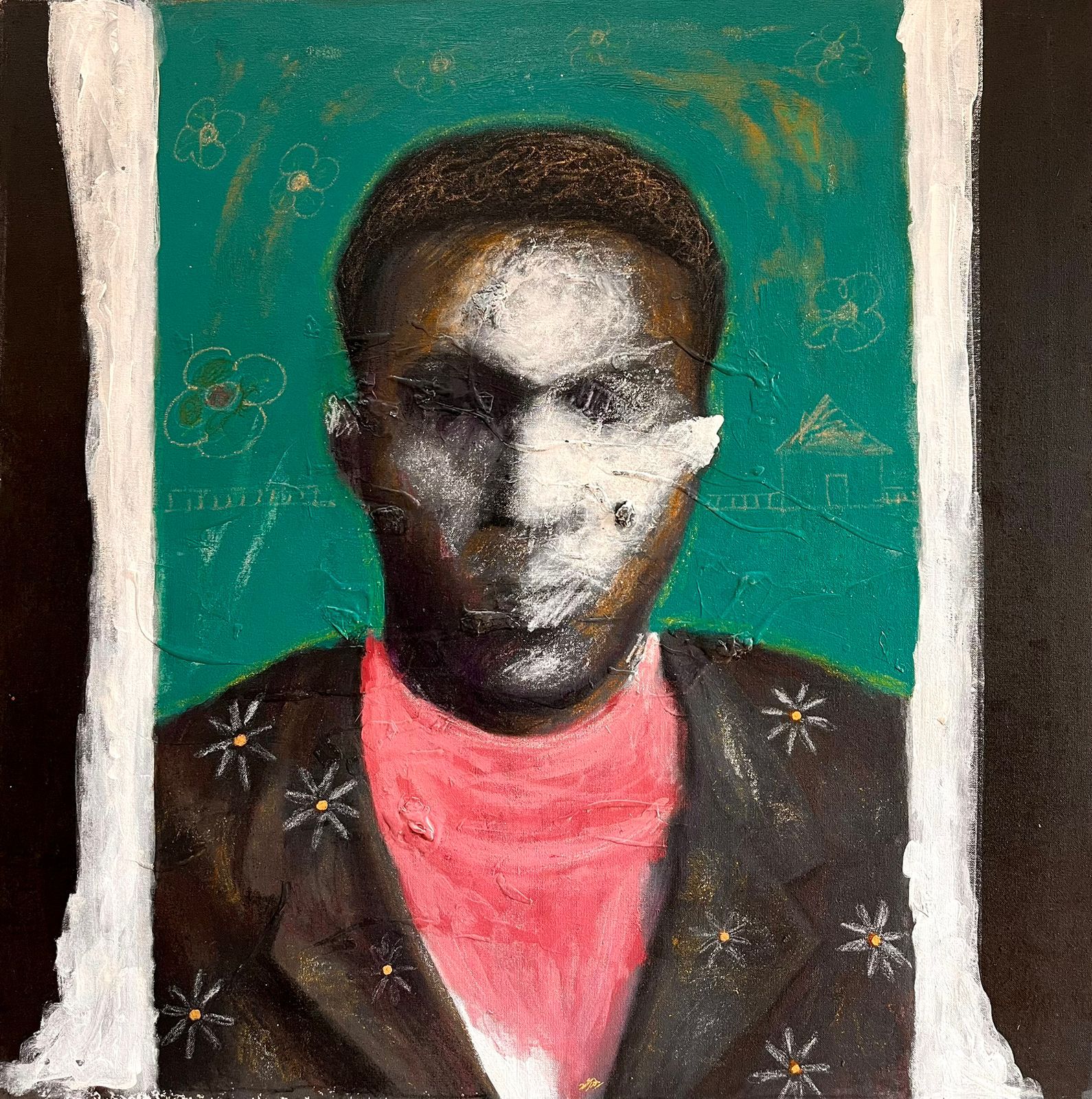

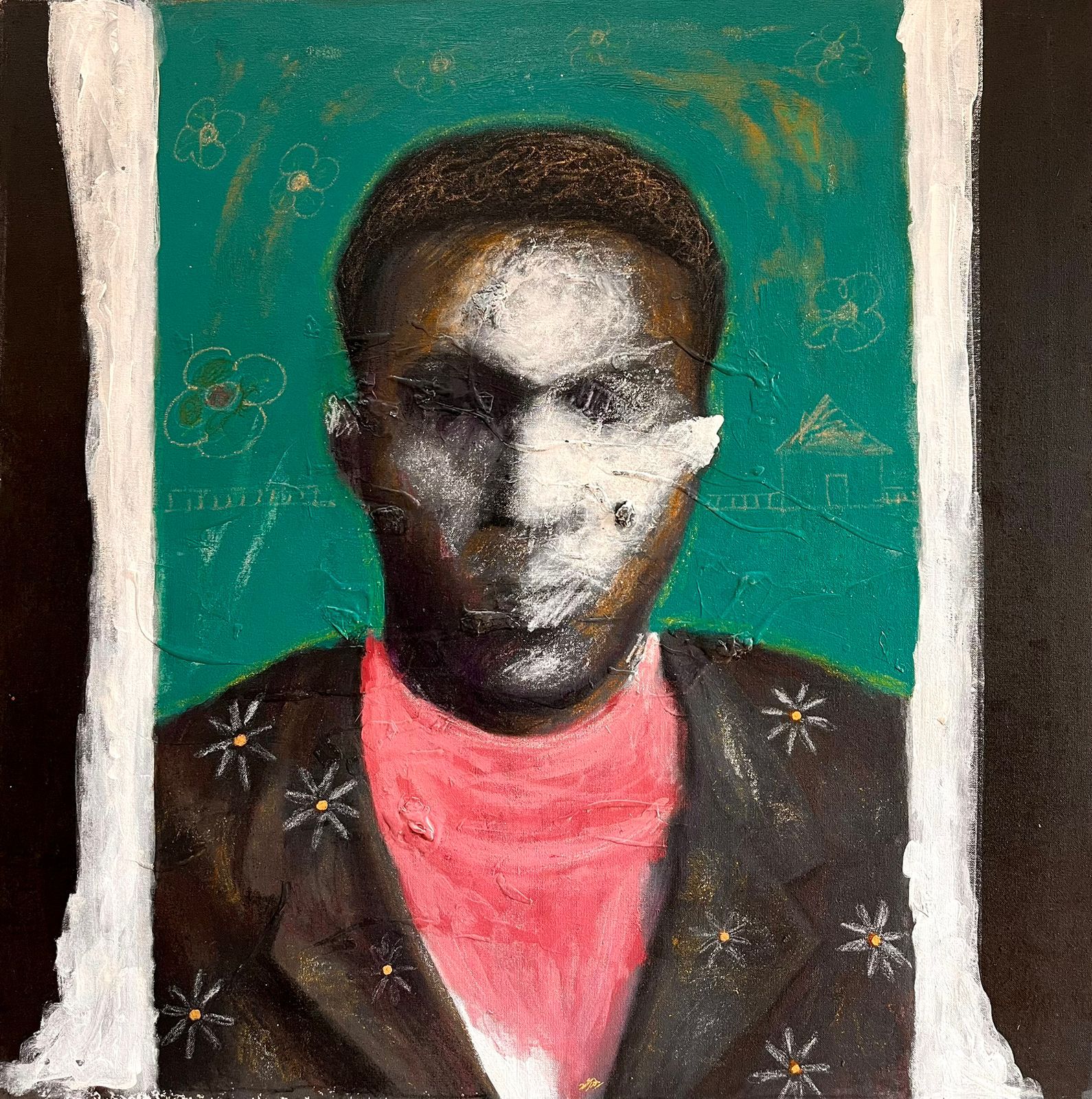

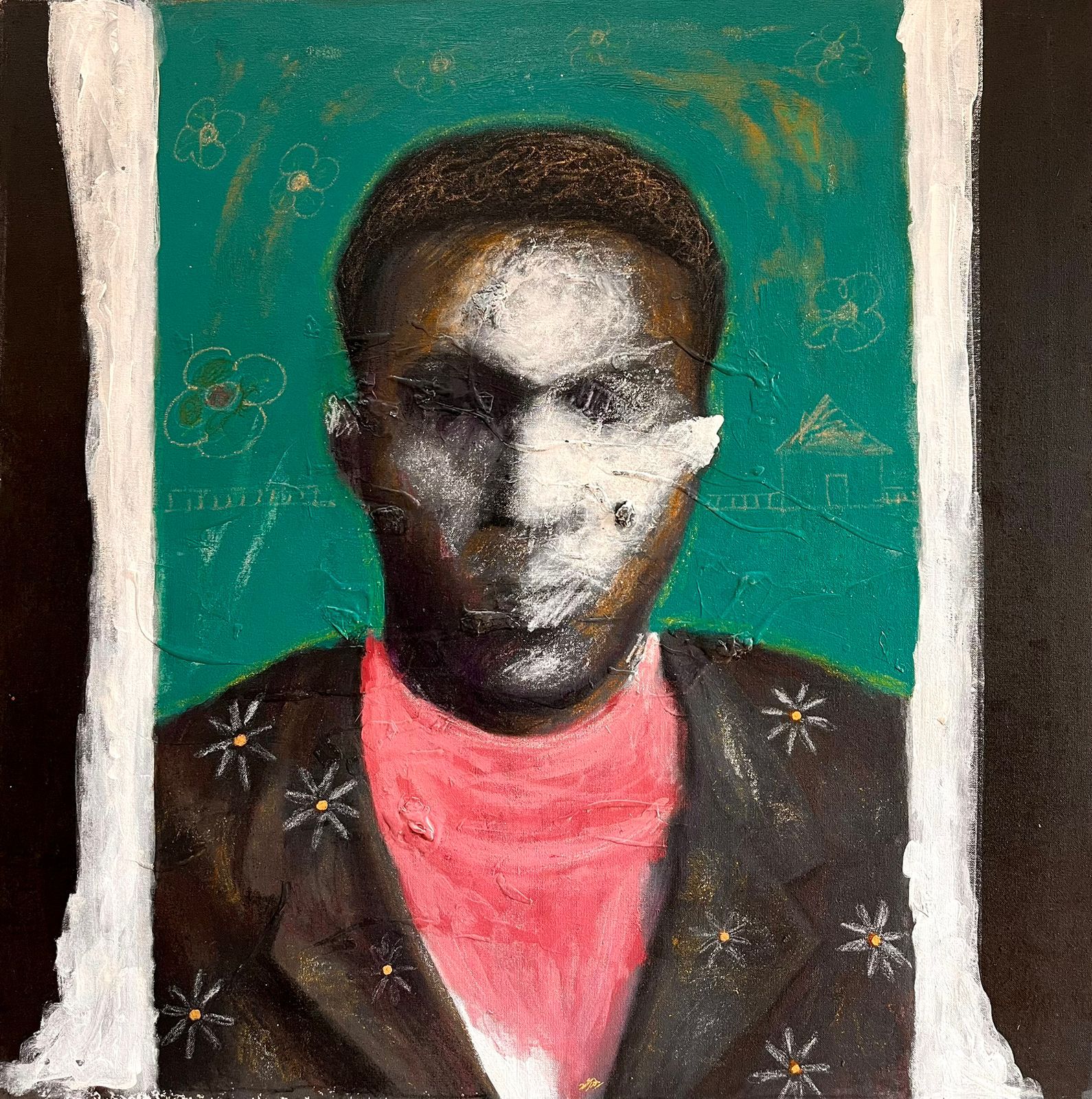

Images 4-6 by Waleed Mohammed

6. I just got my hair done!

Medium: acrylic and pastel on canvas

115x115 cm, 2025

7. Ahmed Osman

Medium: acrylic and wax crayons on canvas

85 x 85 cm, 2025

8. Forever grateful to have stumbled upon you xx

Medium: acrylic and wax crayons on canvas

35 x 40 cm, 2025

Images 7-9 by Abdulla Basher

Artist Statement

I draw inspiration from the simple things around me. A movement or a gesture can hold everything. Within my artistic practice, I work with freedom—abstraction and colour give me this space. I layer, add, and slash until I reach the image that lies within me, waiting to be revealed.

Shilla is a Sudanese art collective based in Nairobi, Kenya.

Amani Azhari (b.1998) visual artist from Sudan, received her bachelor's in fine and Applied Arts in 2022 from University of Sudan. and participated in numerous internal exhibitions in her home country. After obtaining her Bachelor's degree in Fine and Applied Arts from the University of Sudan in 2022, she ventured to Kampala, Uganda. Continuing her artistic journey through residencies and exhibitions, she has recently been painting from her studio in Nairobi, Kenya. Amani finds inspiration in girls' sessions, where they express their thoughts and experiences in a society that often silences them with numerous restrictions. Through these sessions, she shares blame, fears, and even beautiful sentiments that are difficult to disclose publicly. Utilizing girls as a fundamental element in her expression, she draws from her personal features to strengthen her message.

Waleed Mohammed (wamo) born in 2000, is a Sudanese visual artist based in Nairobi, Kenya. Following the outbreak of war in Sudan in 2023, his experience of forced exile has profoundly informed his artistic practice and commitment. His mixed media practice explores identity, exile, and memory through archival materials, found images, text, and bureaucratic objects such as passport photographs and oficial documents. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in Fine and Applied Arts from Sudan University of Science and Technology and trained at the Khartoum Art Training Center. His work has been exhibited internationally, and he is a co-founder of Shilla Art Collective in Nairobi. He identifies as part of a national and cultural minority shaped by war, displacement, and prolonged political violence.

Abdalla Basher, born in Sudan in 1979, graduated from the College of Fine and Applied Arts at the University of Sudan, Department of Painting, in 2004. He has participated in numerous exhibitions and workshops both within Sudan and internationally, including in Dubai, Uganda, Ethiopia, and Cairo. From 2021 to 2025, Abdalla was awarded an artist residency in Sweden, during which he presented several exhibitions. His participation included the Örebro Open Art Biennale (2022), Contemporary Garage, exhibitions at Sandviken Kulturcentrum, Konstfrämjandet Örebro, Piteå Konsthallen, Fullersta Gård in Stockholm, Konst Bunkern, Laxå Konsthall, and Köpings Museum. His works are part of public collections in several Swedish municipalities as well as the Västerås Art Museum.

BY SHILLA COLLECTIVE

شلة

yellow the manifesto

SHILLA ART COLLECTIVE, MANIFSTO (0) 26/7/2025

In the heart of Nairobi, beneath an unnamed sky, a group of Sudanese artists found themselves exiled by the war of April 15th. Out of the ashes of that catastrophe, “Shilla” emerged — a form compelled into existence, nourished by artistic urgency, and grown into the seed of a new Sudanese artistic experiment: one that is free, curious, and collaborative.

“Shilla” is not a passing formation; it is a fervent and sincere attempt to reimagine modes of artistic organization under exceptional circumstances. It is an act of resistance, an open house, and a shared space animated by dialogue, driven by the thrill of discovery, and attuned to the boundless possibilities of art.

On Context

In the context of exile, far from Khartoum, and within an unfamiliar artistic landscape, “Shilla” found itself confronted with an unknown space — one that stirred its instincts and compelled it to question itself and its creative process, through openness to the experiences and approaches of others in art and cultural work.

Nairobi’s artistic scene, despite its diversity, is marked by clear organizational structures rooted in collaborative practice — especially through what is globally known as “art collectives.”

Yet when this term is translated into Arabic, it is often rendered as “tajammu‘ fanī(تجمع فني )” (art group) — a descriptive phrase that fails to capture the structural, functional, and relational weight of the original concept. “Tajammu‘” merely implies the numerical presence of three or more individuals, without reflecting the nature of the relationships between them, their organizational fabric, or their shared objectives.

It is also a static term — devoid of the connotations of action, historical accumulation, and the dynamic qualities that are meant to define the essence of an art collective.

One might suggest instead the term “ta‘āwuniyya fanīya)” (artistic cooperative), which aligns more closely with the functional reality of the concept. It suggests a productive relationship, with temporal continuity and mutual investment in a long-term artistic endeavor.

However, even this term remains burdened by economic overtones — particularly in the Sudanese context, where “cooperatives” have historically been understood as materially driven entities. In this way, the term loses its ability to express the emotional and human dimensions that distinguish an art collective, and fails to capture the social and cultural ties that bind its members together.

It is out of this semantic gap that the term “Shilla” is proposed — a cultural and artistic alternative that carries emotional and conceptual weight. Linguistically, the word refers to a circle of close friends, which immediately affirms the affective and social nature of this artistic formation.

“Shilla” is not merely a numerical label; it is a linguistic and philosophical proposal that reflects the quality of relational ties between members.

In everyday usage, “Shilla” describes a group of emotionally bonded individuals whose connection is not based solely on a shared goal or fixed project, but rather on a meshwork of cultural, artistic, and intellectual relationships — nourished by a collective desire for change or for exploring new possibilities.

The selection of this word reflects not only the actual conditions that gave rise to the group, but also a vision of artistic practice as an extension of human relation — as something rooted in trust, mutual care, and unconditional belonging.

Metaphorically, the word evokes the image of “a bundle of entangled threads” — a symbol of interweaving, integration, and cohesion, achieved despite difference and variation among its members.

Within Sudanese cultural memory, “Shilla” also bears a strong emotional resonance: it expresses solidarity, affection, and a sense of belonging — all of which form the emotional and social infrastructure of this collaborative project.

Thus, “Shilla” is not a linguistic workaround or poetic evasion of failed translation. It is both a linguistic and existential critique, a means by which the founding group seeks to carve out a space that bears their voice, memory, and form — without severing ties with global artistic practices.

The term resists pre-packaged definitions and attempts instead to generate a concept imbued with poetic, social, and historical charge.

At the same time, “Shilla” serves as a platform for collective artistic production. It does not negate the individual experience, but reframes it within a horizontal network of relations — grounded in dialogue, curiosity, and shared making.

On Collaboration

Organized collaboration has never been a foreign concept to Sudanese public life; rather, it has long been a cornerstone of resistance — politically, socially, and culturally — against colonialism and oppressive regimes.

It is this deeply rooted spirit of cooperation that animates “Shilla” from within. Collaboration, for Shilla, is not a fleeting organizational choice but a continuation of a long historical trajectory of popular action and cultural resistance.

Sudan’s cultural history is dense with artistic and intellectual movements grounded in collective labor: from artists’ unions, to literary and visual art circles, to contemporary grassroots initiatives.“Shilla,” growing out of this lineage, does not seek to break from the past. Instead, it builds upon it — reinterpreting it within a contemporary context, a new exile, and among new comrades and companions.

Nairobi’s artistic landscape, with its diversity and cooperative ethos, has reawakened in Shilla a deep conviction: that collaborative work is not a circumstantial tool, but a necessary condition for the continuity and evolution of artistic creation — especially in a time where political repression coincides with cultural stagnation, and the need for art becomes more vital than ever.

On Isolation

At its core, artistic work is bound to the individuality of the artist — it is they who dream, who judge, who shape the nuances of their human experience into a form of artistic expression.

Yet modern Sudanese artistic practice has long been marked — due to complex historical, political, and cultural forces — by an entrenched individualism that has diminished the collaborative dimension of the artistic process.

This individualism has led to social isolation and institutional marginalization of the artist, rendering the artistic process confined to the self, closed off to the individual experience as the sole path of production.

Such individualism was not merely a rejection of the external world, but often a reaction to a reality in which the support structures of art had deteriorated: exhibition spaces, critical institutions, traditions of artistic dialogue.

In this context, individualism ceased to be a free choice and became instead a coercive condition of production.

Still, “Shilla” does not deny the value of the artist’s individual experience. Rather, it insists on recognizing and deepening that experience — not through withdrawal, but through sustained critical dialogue.

Art does not exist in isolation from its context. The artistic self does not arise in a vacuum, but is refined through interaction with others and through the questions posed by the work itself.

“Shilla” views artistic production as a dialogical path — one that begins from the self and returns to it, mediated by cycles of interaction, discussion, and reflection.

In this way, the individuality of the artist is not threatened but enriched — illuminated from multiple angles through shared looking, mutual interpretation, and artistic exchange.

On Practice

Once the foundational concepts of Shilla’s vision are established, it becomes essential that this vision be reflected in artistic practice itself.

This cooperative does not view the creative process as an isolated act, but as an organic extension of human experience — one that cannot be fulfilled in solitude, nor produced outside relationships of dialogue and exchange.

From this perspective, artistic practice within Shilla is shaped by guiding principles rooted in the artist’s subjective experience and cultural-emotional commitments — producing works that express their existence.

Yet this expression is not concluded with the production of the artwork; rather, it opens into conversations and dialogues that interrogate the work, reframe its meaning, and shift it from a personal space into a collective social and cultural impact.

Shilla sees the creative process as one that does not end at the studio’s threshold. It continues as a reciprocal relationship between the artist and others.

Within this extension, the role of artistic coordination emerges as a fundamental component of the creative process — not as a detached technical function, but as part of a collaborative fabric managed by the group in a spirit of participation.

Although artistic coordination may appear, especially in the Sudanese context, as a separate stage — due to long-standing institutional marginalization — this separation has weakened the social and productive dimensions of art, diminishing its cultural impact and rendering artistic work, in many cases, a closed-off experience.

Shilla rejects this separation, instead reclaiming coordination as a democratic and collaborative practice, inseparable from the broader act of creation.

In doing so, it resists rigid structural divisions and reimagines artistic production as an ongoing dialogue between the individuality of the artist and the surrounding cultural and social environment.

Shilla regards this shared practice as a deeply emotional act — rooted in human collaboration, openness, and the desire to form a collective artistic experience that does not erase individual differences, but illuminates them through exchange, interaction, and dialogue.

In this way, artistic production is realized as a holistic relationship between human beings, society, memory, and the desire to say something honest, shared, and free.

Members

Amani Azhari

Heraa hassan

Hozaifa Elsiddig

Mohamed Wraag

Sannad Shreef

Waleed Mohammed

Yathrip Hassan

Images 1-3 by Amani Azhari, part of Healing Sessions series.

Artist Statement: Historically, women have gathered in intimate spaces that served as sanctuaries for healing and support—safe environments where they could share openly without fear of judgment or criticism. These gatherings often focused on the deeply personal and painful realities of sexual violence and other forms of abuse—experiences that were frequently endured in silence.

For many young women, understanding their identity and worth is a journey that takes time, patience, and introspection. Untangling personal narratives from the misconceptions imposed by society is not always easy. Recognizing where external narratives end and where our authentic stories begin can be both challenging and courageous—but it is an essential step toward living truthfully and freely. This is where the seed of healing is planted.

Every woman who heals herself contributes not only to her own well-being but also to the healing of the women who came before her and those who will come after. Womanhood is deeply rooted in the power of reception, reflection, and renewal. The more a woman becomes aware of the psychological impact of her environment, the better equipped she is to break cycles of trauma and prevent them from passing on to future generations.

The traumas we experience shape not only our inner world but also our outward expressions. When we begin to heal, it shows in our presence—our features become softer, more vibrant, and more at ease, reflecting the peace we cultivate within.

These healing sessions have continually inspired Amani in her work. She is deeply moved by the authenticity that arises when women are invited to sit together, express themselves freely, and draw strength from one another. It is in these moments of shared vulnerability and resilience that women begin to transform. Amani believes that true healing starts from within, and once internal harmony is restored, life itself begins to change in profound ways.

These gatherings often take place in the home—a space symbolizing comfort, calm, and cherished memories—making it the ideal setting for healing to begin.

Images 4-6 by Waleed Mohammed

6. I just got my hair done!

Medium: acrylic and pastel on canvas

115x115 cm, 2025

7. Ahmed Osman

Medium: acrylic and wax crayons on canvas

85 x 85 cm, 2025

8. Forever grateful to have stumbled upon you xx

Medium: acrylic and wax crayons on canvas

35 x 40 cm, 2025

Images 7-9 by Abdulla Basher

Artist Statement

I draw inspiration from the simple things around me. A movement or a gesture can hold everything. Within my artistic practice, I work with freedom—abstraction and colour give me this space. I layer, add, and slash until I reach the image that lies within me, waiting to be revealed.

شلة

yellow the manifesto

SHILLA ART COLLECTIVE, MANIFSTO (0) 26/7/2025

In the heart of Nairobi, beneath an unnamed sky, a group of Sudanese artists found themselves exiled by the war of April 15th. Out of the ashes of that catastrophe, “Shilla” emerged — a form compelled into existence, nourished by artistic urgency, and grown into the seed of a new Sudanese artistic experiment: one that is free, curious, and collaborative.

“Shilla” is not a passing formation; it is a fervent and sincere attempt to reimagine modes of artistic organization under exceptional circumstances. It is an act of resistance, an open house, and a shared space animated by dialogue, driven by the thrill of discovery, and attuned to the boundless possibilities of art.

On Context

In the context of exile, far from Khartoum, and within an unfamiliar artistic landscape, “Shilla” found itself confronted with an unknown space — one that stirred its instincts and compelled it to question itself and its creative process, through openness to the experiences and approaches of others in art and cultural work.

Nairobi’s artistic scene, despite its diversity, is marked by clear organizational structures rooted in collaborative practice — especially through what is globally known as “art collectives.”

Yet when this term is translated into Arabic, it is often rendered as “tajammu‘ fanī(تجمع فني )” (art group) — a descriptive phrase that fails to capture the structural, functional, and relational weight of the original concept. “Tajammu‘” merely implies the numerical presence of three or more individuals, without reflecting the nature of the relationships between them, their organizational fabric, or their shared objectives.

It is also a static term — devoid of the connotations of action, historical accumulation, and the dynamic qualities that are meant to define the essence of an art collective.

One might suggest instead the term “ta‘āwuniyya fanīya)” (artistic cooperative), which aligns more closely with the functional reality of the concept. It suggests a productive relationship, with temporal continuity and mutual investment in a long-term artistic endeavor.

However, even this term remains burdened by economic overtones — particularly in the Sudanese context, where “cooperatives” have historically been understood as materially driven entities. In this way, the term loses its ability to express the emotional and human dimensions that distinguish an art collective, and fails to capture the social and cultural ties that bind its members together.

It is out of this semantic gap that the term “Shilla” is proposed — a cultural and artistic alternative that carries emotional and conceptual weight. Linguistically, the word refers to a circle of close friends, which immediately affirms the affective and social nature of this artistic formation.

“Shilla” is not merely a numerical label; it is a linguistic and philosophical proposal that reflects the quality of relational ties between members.

In everyday usage, “Shilla” describes a group of emotionally bonded individuals whose connection is not based solely on a shared goal or fixed project, but rather on a meshwork of cultural, artistic, and intellectual relationships — nourished by a collective desire for change or for exploring new possibilities.

The selection of this word reflects not only the actual conditions that gave rise to the group, but also a vision of artistic practice as an extension of human relation — as something rooted in trust, mutual care, and unconditional belonging.

Metaphorically, the word evokes the image of “a bundle of entangled threads” — a symbol of interweaving, integration, and cohesion, achieved despite difference and variation among its members.

Within Sudanese cultural memory, “Shilla” also bears a strong emotional resonance: it expresses solidarity, affection, and a sense of belonging — all of which form the emotional and social infrastructure of this collaborative project.

Thus, “Shilla” is not a linguistic workaround or poetic evasion of failed translation. It is both a linguistic and existential critique, a means by which the founding group seeks to carve out a space that bears their voice, memory, and form — without severing ties with global artistic practices.

The term resists pre-packaged definitions and attempts instead to generate a concept imbued with poetic, social, and historical charge.

At the same time, “Shilla” serves as a platform for collective artistic production. It does not negate the individual experience, but reframes it within a horizontal network of relations — grounded in dialogue, curiosity, and shared making.

On Collaboration

Organized collaboration has never been a foreign concept to Sudanese public life; rather, it has long been a cornerstone of resistance — politically, socially, and culturally — against colonialism and oppressive regimes.

It is this deeply rooted spirit of cooperation that animates “Shilla” from within. Collaboration, for Shilla, is not a fleeting organizational choice but a continuation of a long historical trajectory of popular action and cultural resistance.

Sudan’s cultural history is dense with artistic and intellectual movements grounded in collective labor: from artists’ unions, to literary and visual art circles, to contemporary grassroots initiatives.“Shilla,” growing out of this lineage, does not seek to break from the past. Instead, it builds upon it — reinterpreting it within a contemporary context, a new exile, and among new comrades and companions.

Nairobi’s artistic landscape, with its diversity and cooperative ethos, has reawakened in Shilla a deep conviction: that collaborative work is not a circumstantial tool, but a necessary condition for the continuity and evolution of artistic creation — especially in a time where political repression coincides with cultural stagnation, and the need for art becomes more vital than ever.

On Isolation

At its core, artistic work is bound to the individuality of the artist — it is they who dream, who judge, who shape the nuances of their human experience into a form of artistic expression.

Yet modern Sudanese artistic practice has long been marked — due to complex historical, political, and cultural forces — by an entrenched individualism that has diminished the collaborative dimension of the artistic process.

This individualism has led to social isolation and institutional marginalization of the artist, rendering the artistic process confined to the self, closed off to the individual experience as the sole path of production.

Such individualism was not merely a rejection of the external world, but often a reaction to a reality in which the support structures of art had deteriorated: exhibition spaces, critical institutions, traditions of artistic dialogue.

In this context, individualism ceased to be a free choice and became instead a coercive condition of production.

Still, “Shilla” does not deny the value of the artist’s individual experience. Rather, it insists on recognizing and deepening that experience — not through withdrawal, but through sustained critical dialogue.

Art does not exist in isolation from its context. The artistic self does not arise in a vacuum, but is refined through interaction with others and through the questions posed by the work itself.

“Shilla” views artistic production as a dialogical path — one that begins from the self and returns to it, mediated by cycles of interaction, discussion, and reflection.

In this way, the individuality of the artist is not threatened but enriched — illuminated from multiple angles through shared looking, mutual interpretation, and artistic exchange.

On Practice

Once the foundational concepts of Shilla’s vision are established, it becomes essential that this vision be reflected in artistic practice itself.

This cooperative does not view the creative process as an isolated act, but as an organic extension of human experience — one that cannot be fulfilled in solitude, nor produced outside relationships of dialogue and exchange.

From this perspective, artistic practice within Shilla is shaped by guiding principles rooted in the artist’s subjective experience and cultural-emotional commitments — producing works that express their existence.

Yet this expression is not concluded with the production of the artwork; rather, it opens into conversations and dialogues that interrogate the work, reframe its meaning, and shift it from a personal space into a collective social and cultural impact.

Shilla sees the creative process as one that does not end at the studio’s threshold. It continues as a reciprocal relationship between the artist and others.

Within this extension, the role of artistic coordination emerges as a fundamental component of the creative process — not as a detached technical function, but as part of a collaborative fabric managed by the group in a spirit of participation.

Although artistic coordination may appear, especially in the Sudanese context, as a separate stage — due to long-standing institutional marginalization — this separation has weakened the social and productive dimensions of art, diminishing its cultural impact and rendering artistic work, in many cases, a closed-off experience.

Shilla rejects this separation, instead reclaiming coordination as a democratic and collaborative practice, inseparable from the broader act of creation.

In doing so, it resists rigid structural divisions and reimagines artistic production as an ongoing dialogue between the individuality of the artist and the surrounding cultural and social environment.

Shilla regards this shared practice as a deeply emotional act — rooted in human collaboration, openness, and the desire to form a collective artistic experience that does not erase individual differences, but illuminates them through exchange, interaction, and dialogue.

In this way, artistic production is realized as a holistic relationship between human beings, society, memory, and the desire to say something honest, shared, and free.

Members

Amani Azhari

Heraa hassan

Hozaifa Elsiddig

Mohamed Wraag

Sannad Shreef

Waleed Mohammed

Yathrip Hassan

Images 1-3 by Amani Azhari, part of Healing Sessions series.

Artist Statement: Historically, women have gathered in intimate spaces that served as sanctuaries for healing and support—safe environments where they could share openly without fear of judgment or criticism. These gatherings often focused on the deeply personal and painful realities of sexual violence and other forms of abuse—experiences that were frequently endured in silence.

For many young women, understanding their identity and worth is a journey that takes time, patience, and introspection. Untangling personal narratives from the misconceptions imposed by society is not always easy. Recognizing where external narratives end and where our authentic stories begin can be both challenging and courageous—but it is an essential step toward living truthfully and freely. This is where the seed of healing is planted.

Every woman who heals herself contributes not only to her own well-being but also to the healing of the women who came before her and those who will come after. Womanhood is deeply rooted in the power of reception, reflection, and renewal. The more a woman becomes aware of the psychological impact of her environment, the better equipped she is to break cycles of trauma and prevent them from passing on to future generations.

The traumas we experience shape not only our inner world but also our outward expressions. When we begin to heal, it shows in our presence—our features become softer, more vibrant, and more at ease, reflecting the peace we cultivate within.

These healing sessions have continually inspired Amani in her work. She is deeply moved by the authenticity that arises when women are invited to sit together, express themselves freely, and draw strength from one another. It is in these moments of shared vulnerability and resilience that women begin to transform. Amani believes that true healing starts from within, and once internal harmony is restored, life itself begins to change in profound ways.

These gatherings often take place in the home—a space symbolizing comfort, calm, and cherished memories—making it the ideal setting for healing to begin.

Images 4-6 by Waleed Mohammed

6. I just got my hair done!

Medium: acrylic and pastel on canvas

115x115 cm, 2025

7. Ahmed Osman

Medium: acrylic and wax crayons on canvas

85 x 85 cm, 2025

8. Forever grateful to have stumbled upon you xx

Medium: acrylic and wax crayons on canvas

35 x 40 cm, 2025

Images 7-9 by Abdulla Basher

Artist Statement

I draw inspiration from the simple things around me. A movement or a gesture can hold everything. Within my artistic practice, I work with freedom—abstraction and colour give me this space. I layer, add, and slash until I reach the image that lies within me, waiting to be revealed.

Shilla is a Sudanese art collective based in Nairobi, Kenya.

Amani Azhari (b.1998) visual artist from Sudan, received her bachelor's in fine and Applied Arts in 2022 from University of Sudan. and participated in numerous internal exhibitions in her home country. After obtaining her Bachelor's degree in Fine and Applied Arts from the University of Sudan in 2022, she ventured to Kampala, Uganda. Continuing her artistic journey through residencies and exhibitions, she has recently been painting from her studio in Nairobi, Kenya. Amani finds inspiration in girls' sessions, where they express their thoughts and experiences in a society that often silences them with numerous restrictions. Through these sessions, she shares blame, fears, and even beautiful sentiments that are difficult to disclose publicly. Utilizing girls as a fundamental element in her expression, she draws from her personal features to strengthen her message.

Waleed Mohammed (wamo) born in 2000, is a Sudanese visual artist based in Nairobi, Kenya. Following the outbreak of war in Sudan in 2023, his experience of forced exile has profoundly informed his artistic practice and commitment. His mixed media practice explores identity, exile, and memory through archival materials, found images, text, and bureaucratic objects such as passport photographs and oficial documents. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in Fine and Applied Arts from Sudan University of Science and Technology and trained at the Khartoum Art Training Center. His work has been exhibited internationally, and he is a co-founder of Shilla Art Collective in Nairobi. He identifies as part of a national and cultural minority shaped by war, displacement, and prolonged political violence.

Abdalla Basher, born in Sudan in 1979, graduated from the College of Fine and Applied Arts at the University of Sudan, Department of Painting, in 2004. He has participated in numerous exhibitions and workshops both within Sudan and internationally, including in Dubai, Uganda, Ethiopia, and Cairo. From 2021 to 2025, Abdalla was awarded an artist residency in Sweden, during which he presented several exhibitions. His participation included the Örebro Open Art Biennale (2022), Contemporary Garage, exhibitions at Sandviken Kulturcentrum, Konstfrämjandet Örebro, Piteå Konsthallen, Fullersta Gård in Stockholm, Konst Bunkern, Laxå Konsthall, and Köpings Museum. His works are part of public collections in several Swedish municipalities as well as the Västerås Art Museum.

BY SHILLA COLLECTIVE

شلة

yellow the manifesto

SHILLA ART COLLECTIVE, MANIFSTO (0) 26/7/2025

In the heart of Nairobi, beneath an unnamed sky, a group of Sudanese artists found themselves exiled by the war of April 15th. Out of the ashes of that catastrophe, “Shilla” emerged — a form compelled into existence, nourished by artistic urgency, and grown into the seed of a new Sudanese artistic experiment: one that is free, curious, and collaborative.

“Shilla” is not a passing formation; it is a fervent and sincere attempt to reimagine modes of artistic organization under exceptional circumstances. It is an act of resistance, an open house, and a shared space animated by dialogue, driven by the thrill of discovery, and attuned to the boundless possibilities of art.

On Context

In the context of exile, far from Khartoum, and within an unfamiliar artistic landscape, “Shilla” found itself confronted with an unknown space — one that stirred its instincts and compelled it to question itself and its creative process, through openness to the experiences and approaches of others in art and cultural work.

Nairobi’s artistic scene, despite its diversity, is marked by clear organizational structures rooted in collaborative practice — especially through what is globally known as “art collectives.”

Yet when this term is translated into Arabic, it is often rendered as “tajammu‘ fanī(تجمع فني )” (art group) — a descriptive phrase that fails to capture the structural, functional, and relational weight of the original concept. “Tajammu‘” merely implies the numerical presence of three or more individuals, without reflecting the nature of the relationships between them, their organizational fabric, or their shared objectives.

It is also a static term — devoid of the connotations of action, historical accumulation, and the dynamic qualities that are meant to define the essence of an art collective.

One might suggest instead the term “ta‘āwuniyya fanīya)” (artistic cooperative), which aligns more closely with the functional reality of the concept. It suggests a productive relationship, with temporal continuity and mutual investment in a long-term artistic endeavor.

However, even this term remains burdened by economic overtones — particularly in the Sudanese context, where “cooperatives” have historically been understood as materially driven entities. In this way, the term loses its ability to express the emotional and human dimensions that distinguish an art collective, and fails to capture the social and cultural ties that bind its members together.

It is out of this semantic gap that the term “Shilla” is proposed — a cultural and artistic alternative that carries emotional and conceptual weight. Linguistically, the word refers to a circle of close friends, which immediately affirms the affective and social nature of this artistic formation.

“Shilla” is not merely a numerical label; it is a linguistic and philosophical proposal that reflects the quality of relational ties between members.

In everyday usage, “Shilla” describes a group of emotionally bonded individuals whose connection is not based solely on a shared goal or fixed project, but rather on a meshwork of cultural, artistic, and intellectual relationships — nourished by a collective desire for change or for exploring new possibilities.

The selection of this word reflects not only the actual conditions that gave rise to the group, but also a vision of artistic practice as an extension of human relation — as something rooted in trust, mutual care, and unconditional belonging.

Metaphorically, the word evokes the image of “a bundle of entangled threads” — a symbol of interweaving, integration, and cohesion, achieved despite difference and variation among its members.

Within Sudanese cultural memory, “Shilla” also bears a strong emotional resonance: it expresses solidarity, affection, and a sense of belonging — all of which form the emotional and social infrastructure of this collaborative project.

Thus, “Shilla” is not a linguistic workaround or poetic evasion of failed translation. It is both a linguistic and existential critique, a means by which the founding group seeks to carve out a space that bears their voice, memory, and form — without severing ties with global artistic practices.

The term resists pre-packaged definitions and attempts instead to generate a concept imbued with poetic, social, and historical charge.

At the same time, “Shilla” serves as a platform for collective artistic production. It does not negate the individual experience, but reframes it within a horizontal network of relations — grounded in dialogue, curiosity, and shared making.

On Collaboration

Organized collaboration has never been a foreign concept to Sudanese public life; rather, it has long been a cornerstone of resistance — politically, socially, and culturally — against colonialism and oppressive regimes.

It is this deeply rooted spirit of cooperation that animates “Shilla” from within. Collaboration, for Shilla, is not a fleeting organizational choice but a continuation of a long historical trajectory of popular action and cultural resistance.

Sudan’s cultural history is dense with artistic and intellectual movements grounded in collective labor: from artists’ unions, to literary and visual art circles, to contemporary grassroots initiatives.“Shilla,” growing out of this lineage, does not seek to break from the past. Instead, it builds upon it — reinterpreting it within a contemporary context, a new exile, and among new comrades and companions.

Nairobi’s artistic landscape, with its diversity and cooperative ethos, has reawakened in Shilla a deep conviction: that collaborative work is not a circumstantial tool, but a necessary condition for the continuity and evolution of artistic creation — especially in a time where political repression coincides with cultural stagnation, and the need for art becomes more vital than ever.

On Isolation

At its core, artistic work is bound to the individuality of the artist — it is they who dream, who judge, who shape the nuances of their human experience into a form of artistic expression.

Yet modern Sudanese artistic practice has long been marked — due to complex historical, political, and cultural forces — by an entrenched individualism that has diminished the collaborative dimension of the artistic process.

This individualism has led to social isolation and institutional marginalization of the artist, rendering the artistic process confined to the self, closed off to the individual experience as the sole path of production.

Such individualism was not merely a rejection of the external world, but often a reaction to a reality in which the support structures of art had deteriorated: exhibition spaces, critical institutions, traditions of artistic dialogue.

In this context, individualism ceased to be a free choice and became instead a coercive condition of production.

Still, “Shilla” does not deny the value of the artist’s individual experience. Rather, it insists on recognizing and deepening that experience — not through withdrawal, but through sustained critical dialogue.

Art does not exist in isolation from its context. The artistic self does not arise in a vacuum, but is refined through interaction with others and through the questions posed by the work itself.

“Shilla” views artistic production as a dialogical path — one that begins from the self and returns to it, mediated by cycles of interaction, discussion, and reflection.

In this way, the individuality of the artist is not threatened but enriched — illuminated from multiple angles through shared looking, mutual interpretation, and artistic exchange.

On Practice

Once the foundational concepts of Shilla’s vision are established, it becomes essential that this vision be reflected in artistic practice itself.

This cooperative does not view the creative process as an isolated act, but as an organic extension of human experience — one that cannot be fulfilled in solitude, nor produced outside relationships of dialogue and exchange.

From this perspective, artistic practice within Shilla is shaped by guiding principles rooted in the artist’s subjective experience and cultural-emotional commitments — producing works that express their existence.

Yet this expression is not concluded with the production of the artwork; rather, it opens into conversations and dialogues that interrogate the work, reframe its meaning, and shift it from a personal space into a collective social and cultural impact.

Shilla sees the creative process as one that does not end at the studio’s threshold. It continues as a reciprocal relationship between the artist and others.

Within this extension, the role of artistic coordination emerges as a fundamental component of the creative process — not as a detached technical function, but as part of a collaborative fabric managed by the group in a spirit of participation.

Although artistic coordination may appear, especially in the Sudanese context, as a separate stage — due to long-standing institutional marginalization — this separation has weakened the social and productive dimensions of art, diminishing its cultural impact and rendering artistic work, in many cases, a closed-off experience.

Shilla rejects this separation, instead reclaiming coordination as a democratic and collaborative practice, inseparable from the broader act of creation.

In doing so, it resists rigid structural divisions and reimagines artistic production as an ongoing dialogue between the individuality of the artist and the surrounding cultural and social environment.

Shilla regards this shared practice as a deeply emotional act — rooted in human collaboration, openness, and the desire to form a collective artistic experience that does not erase individual differences, but illuminates them through exchange, interaction, and dialogue.

In this way, artistic production is realized as a holistic relationship between human beings, society, memory, and the desire to say something honest, shared, and free.

Members

Amani Azhari

Heraa hassan

Hozaifa Elsiddig

Mohamed Wraag

Sannad Shreef

Waleed Mohammed

Yathrip Hassan

Images 1-3 by Amani Azhari, part of Healing Sessions series.

Artist Statement: Historically, women have gathered in intimate spaces that served as sanctuaries for healing and support—safe environments where they could share openly without fear of judgment or criticism. These gatherings often focused on the deeply personal and painful realities of sexual violence and other forms of abuse—experiences that were frequently endured in silence.

For many young women, understanding their identity and worth is a journey that takes time, patience, and introspection. Untangling personal narratives from the misconceptions imposed by society is not always easy. Recognizing where external narratives end and where our authentic stories begin can be both challenging and courageous—but it is an essential step toward living truthfully and freely. This is where the seed of healing is planted.

Every woman who heals herself contributes not only to her own well-being but also to the healing of the women who came before her and those who will come after. Womanhood is deeply rooted in the power of reception, reflection, and renewal. The more a woman becomes aware of the psychological impact of her environment, the better equipped she is to break cycles of trauma and prevent them from passing on to future generations.

The traumas we experience shape not only our inner world but also our outward expressions. When we begin to heal, it shows in our presence—our features become softer, more vibrant, and more at ease, reflecting the peace we cultivate within.

These healing sessions have continually inspired Amani in her work. She is deeply moved by the authenticity that arises when women are invited to sit together, express themselves freely, and draw strength from one another. It is in these moments of shared vulnerability and resilience that women begin to transform. Amani believes that true healing starts from within, and once internal harmony is restored, life itself begins to change in profound ways.

These gatherings often take place in the home—a space symbolizing comfort, calm, and cherished memories—making it the ideal setting for healing to begin.

Images 4-6 by Waleed Mohammed

6. I just got my hair done!

Medium: acrylic and pastel on canvas

115x115 cm, 2025

7. Ahmed Osman

Medium: acrylic and wax crayons on canvas

85 x 85 cm, 2025

8. Forever grateful to have stumbled upon you xx

Medium: acrylic and wax crayons on canvas

35 x 40 cm, 2025

Images 7-9 by Abdulla Basher

Artist Statement

I draw inspiration from the simple things around me. A movement or a gesture can hold everything. Within my artistic practice, I work with freedom—abstraction and colour give me this space. I layer, add, and slash until I reach the image that lies within me, waiting to be revealed.

شلة

yellow the manifesto

SHILLA ART COLLECTIVE, MANIFSTO (0) 26/7/2025

In the heart of Nairobi, beneath an unnamed sky, a group of Sudanese artists found themselves exiled by the war of April 15th. Out of the ashes of that catastrophe, “Shilla” emerged — a form compelled into existence, nourished by artistic urgency, and grown into the seed of a new Sudanese artistic experiment: one that is free, curious, and collaborative.

“Shilla” is not a passing formation; it is a fervent and sincere attempt to reimagine modes of artistic organization under exceptional circumstances. It is an act of resistance, an open house, and a shared space animated by dialogue, driven by the thrill of discovery, and attuned to the boundless possibilities of art.

On Context

In the context of exile, far from Khartoum, and within an unfamiliar artistic landscape, “Shilla” found itself confronted with an unknown space — one that stirred its instincts and compelled it to question itself and its creative process, through openness to the experiences and approaches of others in art and cultural work.

Nairobi’s artistic scene, despite its diversity, is marked by clear organizational structures rooted in collaborative practice — especially through what is globally known as “art collectives.”

Yet when this term is translated into Arabic, it is often rendered as “tajammu‘ fanī(تجمع فني )” (art group) — a descriptive phrase that fails to capture the structural, functional, and relational weight of the original concept. “Tajammu‘” merely implies the numerical presence of three or more individuals, without reflecting the nature of the relationships between them, their organizational fabric, or their shared objectives.

It is also a static term — devoid of the connotations of action, historical accumulation, and the dynamic qualities that are meant to define the essence of an art collective.

One might suggest instead the term “ta‘āwuniyya fanīya)” (artistic cooperative), which aligns more closely with the functional reality of the concept. It suggests a productive relationship, with temporal continuity and mutual investment in a long-term artistic endeavor.

However, even this term remains burdened by economic overtones — particularly in the Sudanese context, where “cooperatives” have historically been understood as materially driven entities. In this way, the term loses its ability to express the emotional and human dimensions that distinguish an art collective, and fails to capture the social and cultural ties that bind its members together.

It is out of this semantic gap that the term “Shilla” is proposed — a cultural and artistic alternative that carries emotional and conceptual weight. Linguistically, the word refers to a circle of close friends, which immediately affirms the affective and social nature of this artistic formation.

“Shilla” is not merely a numerical label; it is a linguistic and philosophical proposal that reflects the quality of relational ties between members.

In everyday usage, “Shilla” describes a group of emotionally bonded individuals whose connection is not based solely on a shared goal or fixed project, but rather on a meshwork of cultural, artistic, and intellectual relationships — nourished by a collective desire for change or for exploring new possibilities.

The selection of this word reflects not only the actual conditions that gave rise to the group, but also a vision of artistic practice as an extension of human relation — as something rooted in trust, mutual care, and unconditional belonging.

Metaphorically, the word evokes the image of “a bundle of entangled threads” — a symbol of interweaving, integration, and cohesion, achieved despite difference and variation among its members.

Within Sudanese cultural memory, “Shilla” also bears a strong emotional resonance: it expresses solidarity, affection, and a sense of belonging — all of which form the emotional and social infrastructure of this collaborative project.

Thus, “Shilla” is not a linguistic workaround or poetic evasion of failed translation. It is both a linguistic and existential critique, a means by which the founding group seeks to carve out a space that bears their voice, memory, and form — without severing ties with global artistic practices.

The term resists pre-packaged definitions and attempts instead to generate a concept imbued with poetic, social, and historical charge.

At the same time, “Shilla” serves as a platform for collective artistic production. It does not negate the individual experience, but reframes it within a horizontal network of relations — grounded in dialogue, curiosity, and shared making.

On Collaboration

Organized collaboration has never been a foreign concept to Sudanese public life; rather, it has long been a cornerstone of resistance — politically, socially, and culturally — against colonialism and oppressive regimes.

It is this deeply rooted spirit of cooperation that animates “Shilla” from within. Collaboration, for Shilla, is not a fleeting organizational choice but a continuation of a long historical trajectory of popular action and cultural resistance.

Sudan’s cultural history is dense with artistic and intellectual movements grounded in collective labor: from artists’ unions, to literary and visual art circles, to contemporary grassroots initiatives.“Shilla,” growing out of this lineage, does not seek to break from the past. Instead, it builds upon it — reinterpreting it within a contemporary context, a new exile, and among new comrades and companions.

Nairobi’s artistic landscape, with its diversity and cooperative ethos, has reawakened in Shilla a deep conviction: that collaborative work is not a circumstantial tool, but a necessary condition for the continuity and evolution of artistic creation — especially in a time where political repression coincides with cultural stagnation, and the need for art becomes more vital than ever.

On Isolation

At its core, artistic work is bound to the individuality of the artist — it is they who dream, who judge, who shape the nuances of their human experience into a form of artistic expression.

Yet modern Sudanese artistic practice has long been marked — due to complex historical, political, and cultural forces — by an entrenched individualism that has diminished the collaborative dimension of the artistic process.

This individualism has led to social isolation and institutional marginalization of the artist, rendering the artistic process confined to the self, closed off to the individual experience as the sole path of production.

Such individualism was not merely a rejection of the external world, but often a reaction to a reality in which the support structures of art had deteriorated: exhibition spaces, critical institutions, traditions of artistic dialogue.

In this context, individualism ceased to be a free choice and became instead a coercive condition of production.

Still, “Shilla” does not deny the value of the artist’s individual experience. Rather, it insists on recognizing and deepening that experience — not through withdrawal, but through sustained critical dialogue.

Art does not exist in isolation from its context. The artistic self does not arise in a vacuum, but is refined through interaction with others and through the questions posed by the work itself.

“Shilla” views artistic production as a dialogical path — one that begins from the self and returns to it, mediated by cycles of interaction, discussion, and reflection.