INTERVIEW WITH CAROLYN KIRSCHNER

JF - There Is No Such Thing as a Fish explores the role of Zebrafish as model organisms acting as proxies for human bodies and futures, at what moments in the research has this substitution felt particularly uncanny? Has it altered your perception of your own body in any way?

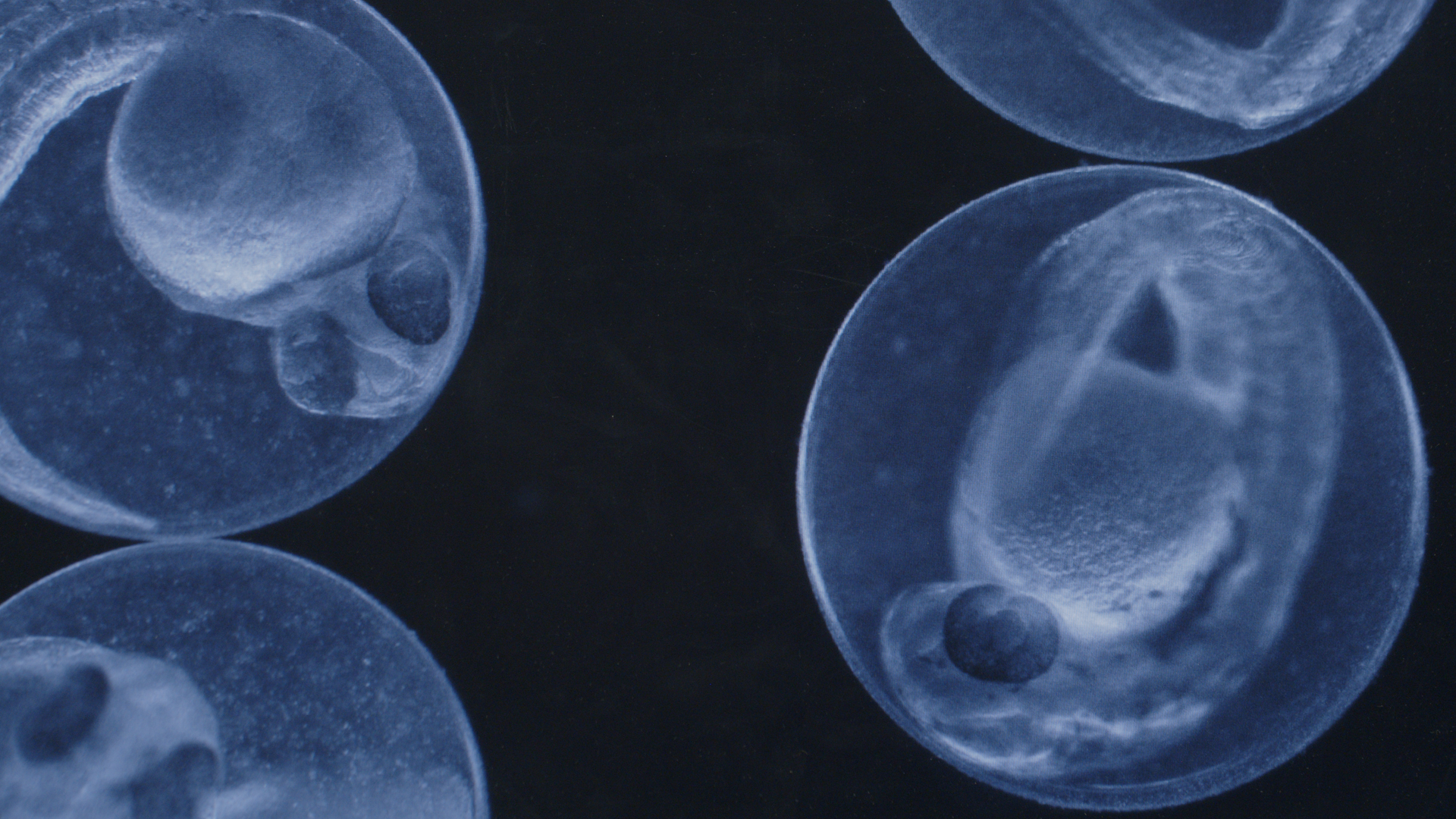

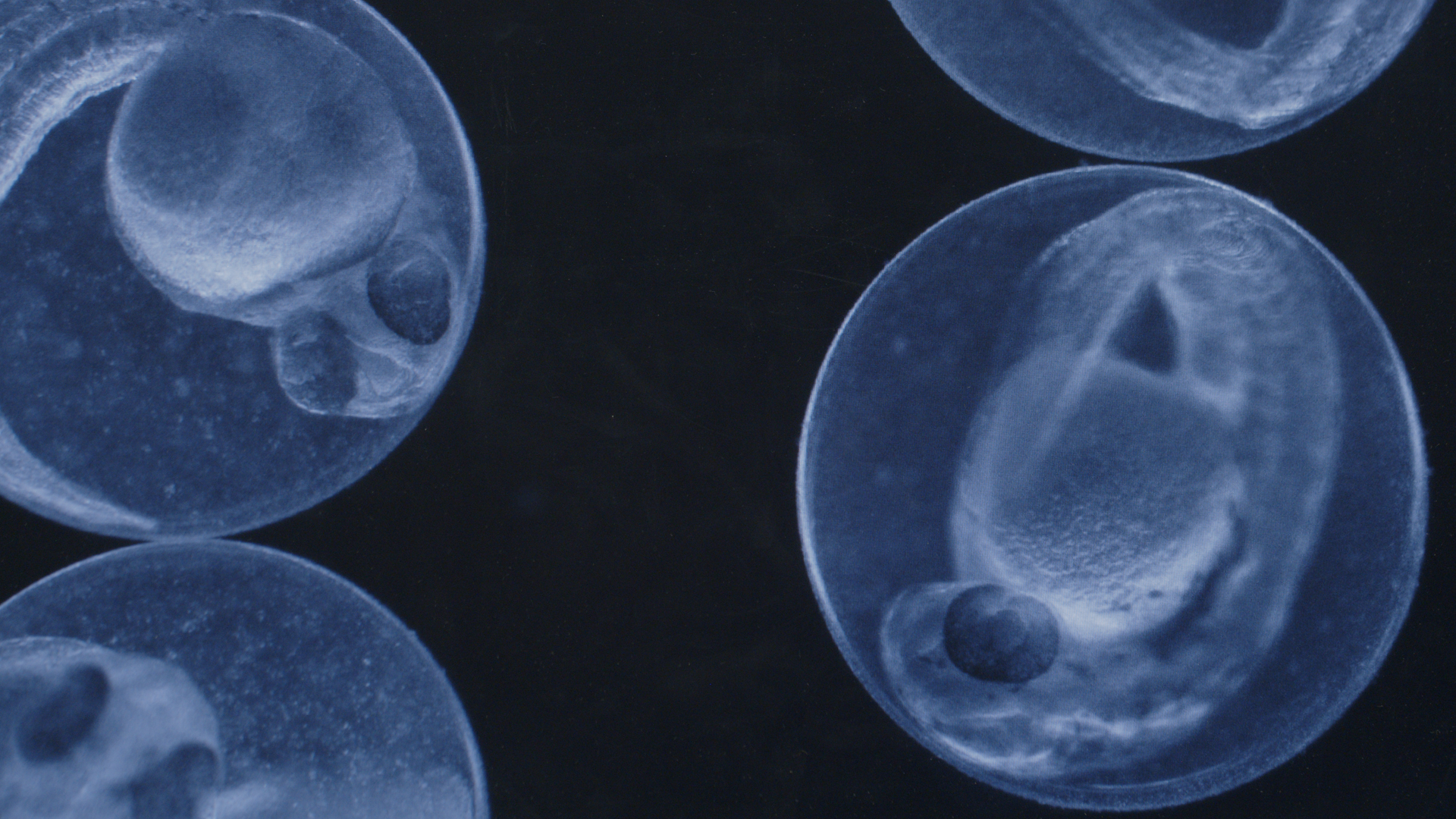

CK - Much of the past year I have spent learning about zebrafish and the commonalities between our bodies – between humans and this small tropical fish. We share around 70% of our genome with zebrafish. We evolved from a common ancestor, an ancient fish that swam the Cambrian seas roughly 450 million years ago. This evolutionary connection means that many of the traits we associate with being uniquely human have actually evolved from fish. Consciousness first evolved from fish. Our capacity for emotions, memory, and learning, too. In the embryonic stage, humans briefly develop gill arches. We have hiccups because of lingering neural circuits that coordinate breathing in fish.

This shared ancestry is precisely why zebrafish are studied today, in the hope of better understanding our own biology and the common principles of life – making them one of the most widely used model organisms in scientific research.

Spending so much time thinking about this small fish, and about how much we have in common, has undoubtedly shifted something in my thinking. It’s pretty amazing – and strangely comforting – to think of my body as a part of this long evolutionary timeline. Worms and sea sponges and jellyfish and all the other beings that came before us – parts of them are still here now.

Another thing that has stuck with me is that, from a strictly taxonomical perspective, apparently ‘fish’ is not a valid biological group, unless it contains all descendants of a common ancestor – unless it includes humans, too. Arguably there is either no such thing as a fish, or we are all fish. I quite like the idea that I am more fish-like than I realised – that my body is less singular, less exceptional, and more continuous with the rest of life than I gave it credit for.

JF - What has the project revealed about the limits of scientific abstraction, and where does the controlled logic of the laboratory come into friction with the unruly, messy realities of lived ecological entanglements?

CK - There Is No Such Thing as a Fish came out of a year-long art-science residency (S+T+ARTS Ec(h)o) working together with scientists from the Physics of Life group across the TUD Dresden University of Technology, the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG), and the Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden (CRTD).

Physics of Life is a relatively new field, driven by a search for the fundamental biological principles, physical laws, and mathematical equations that govern life. In other words, researchers are interested in whether life can be explained through the laws of physics – and, ultimately, whether it is possible to build computational models of living biological systems.

One of the reasons I was drawn to this field of research is a long-standing interest in models. It is a recurring theme across many of my projects: a desire to contend with the role of conceptual, biological, physical, and computational models – and their limitations.

Models are, by definition and by design, abstracted representations of the thing which they seek to describe. They play a hugely important scientific and socio-cultural role, with their ability to make complex systems tangible. In the context of climate science, for example, models are perhaps the only chance to move beyond localised observations, to produce a picture of and make predictions for the planet as a whole.

But the authority of models can also become persuasive in a way that exceeds their scope. The risk is a shift from using models as tools, to imagining that reality itself is fundamentally model-like: computable, predictable, and optimisable. It’s a perspective that disregards the vast and messy complexities of Earth systems, which in fact remain far beyond reach of our current knowledge and computational capacities.

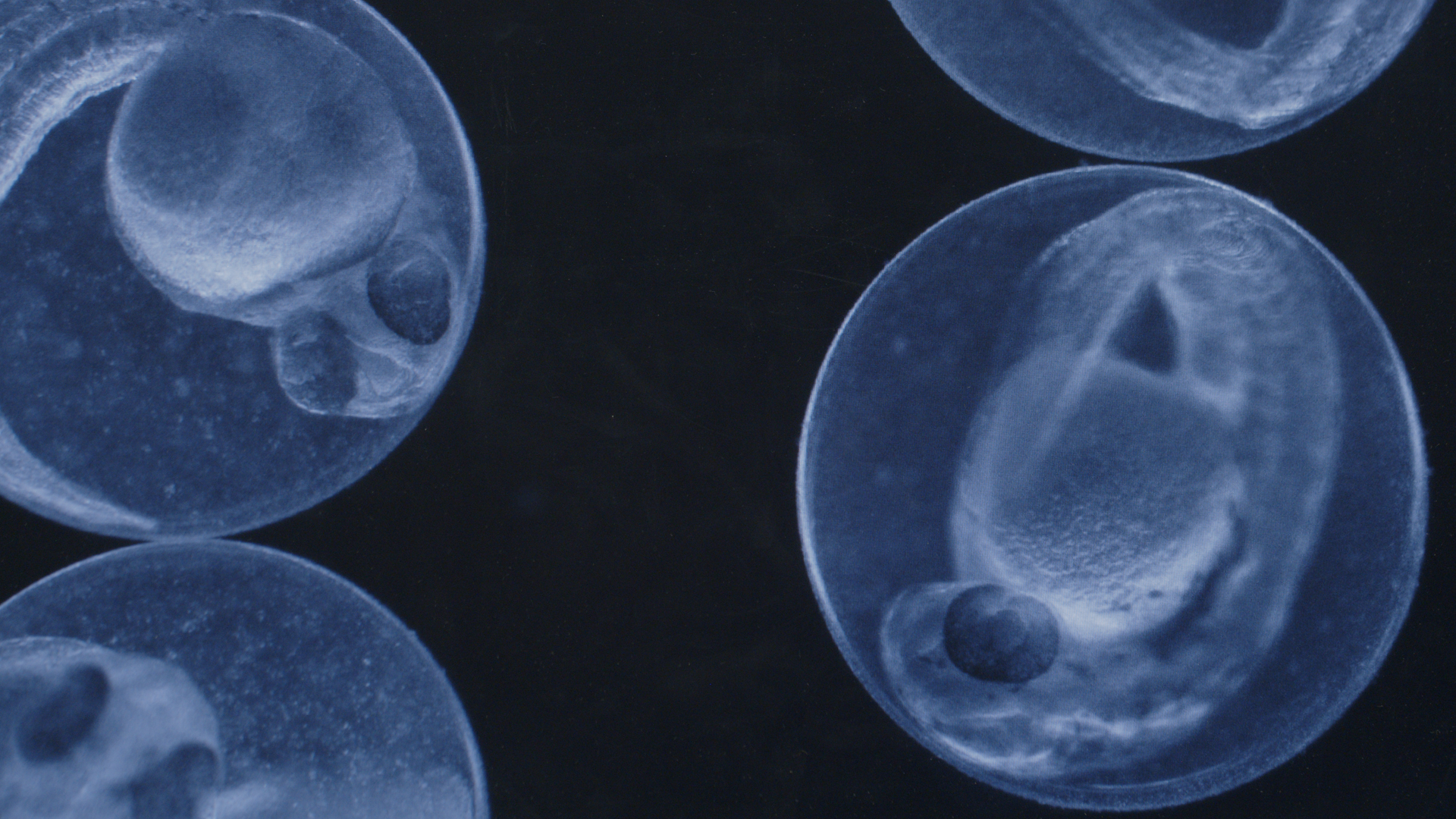

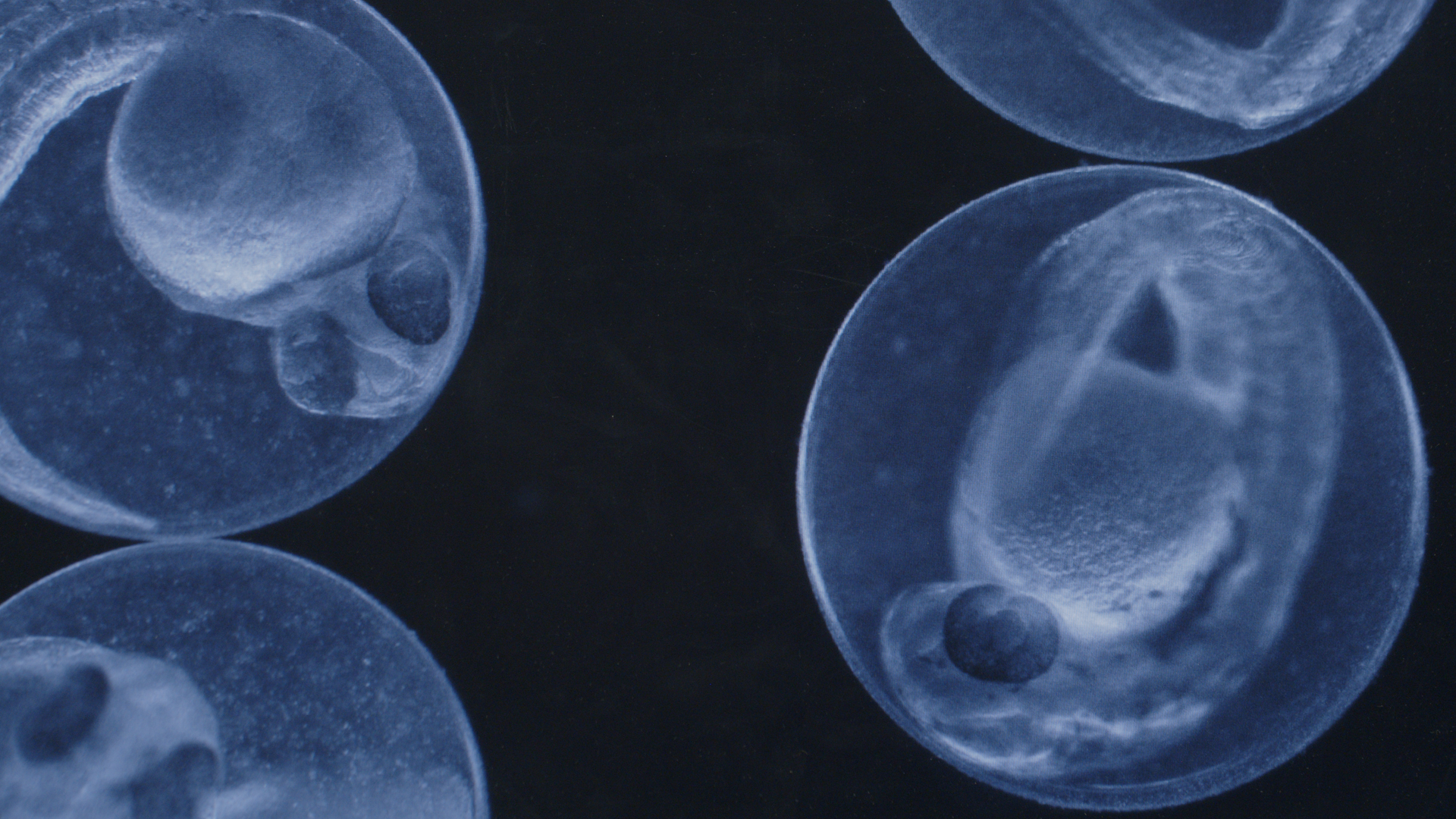

Thinking about models and scientific abstraction specifically in the context of this current project: first, there is the zebrafish itself – used as a living model for the human body. While this substitution is scientifically productive, there is something instinctively confronting about it. What does it mean to use the body of one species as a model or stand-in for another – especially in the face of profound physiological differences between humans and fish?

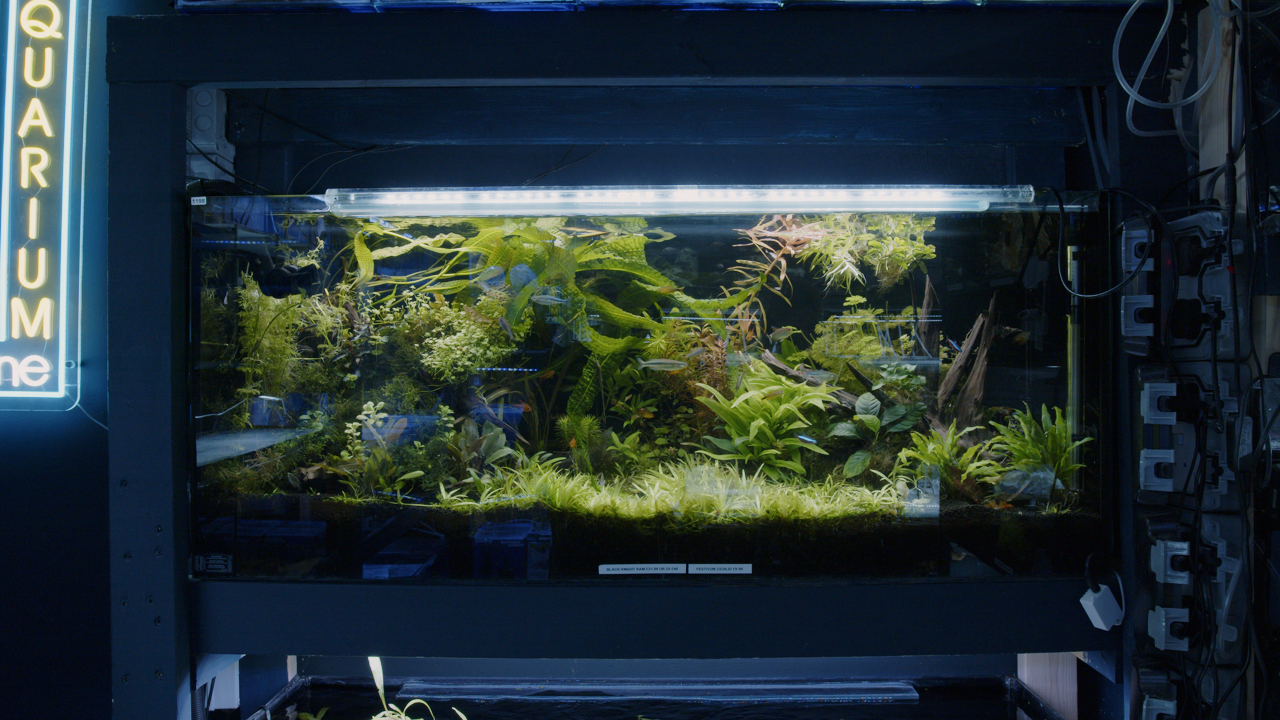

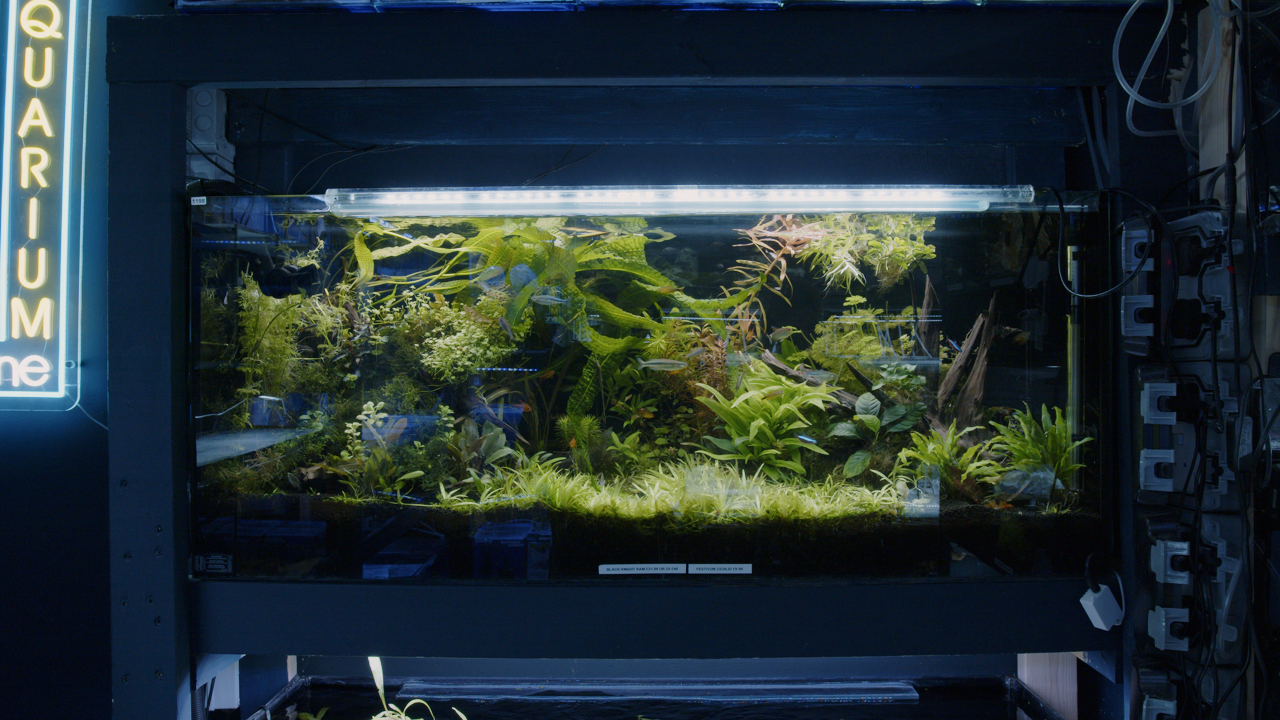

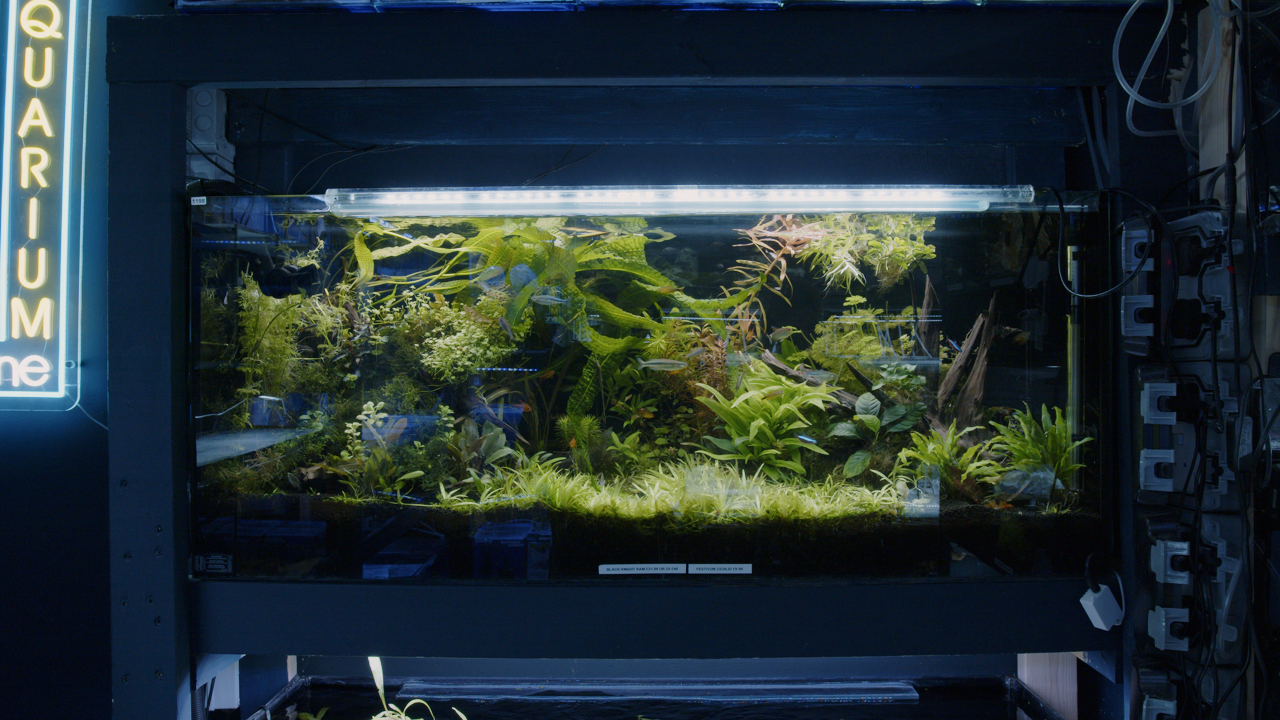

The fish facilities in the laboratory, meanwhile, are a rather uncanny model for the zebrafish’s ecosystems in the wild: with carefully regulated water temperatures and oxygen levels; breeding grounds simulated in sloped plastic dishes; and an environment sanitised of pathogens and predators. Ultimately, it is a highly controlled, artificial world with very little in common with the zebrafish’s wild habitats.

Simultaneously, researchers are attempting to construct computational models of the fish — a model of the model – so that perhaps one day live fish are no longer needed for scientific research. These are some of the multiple layers of abstraction I have come across, each one a step further removed from the original.

And yet even the laboratory fish are no longer quite “original”. Bred for generations in controlled environments, their genomes have diverged from wild populations. The pervasiveness of transgenic lines – fish engineered for particular research purposes – only amplifies this genetic divide. So even as a model to understand its own species in the wild, lab zebrafish are not particularly representative.

Accuracy to ‘the real thing,’ I have come to realise, is not exactly the aim. What is required from models in scientific research is a stable, controllable set of variables – an environment that can be regulated and reproduced. The abstract model is therefore, quite intentionally, untethered from messy ecological realities, and becomes the primary object of study.

What I am hoping to draw out with my project is the visceral weirdness of some of these relationships and layered substitutions – and bring the unruly messiness of ecological entanglements back into focus.

JF - Your fieldwork moves from petri dishes to rivers in northern India, from domestic aquariums to industrial infrastructures. How have these sites altered your perception of scale and intimacy, and where have you felt the boundary between species becoming most porous?

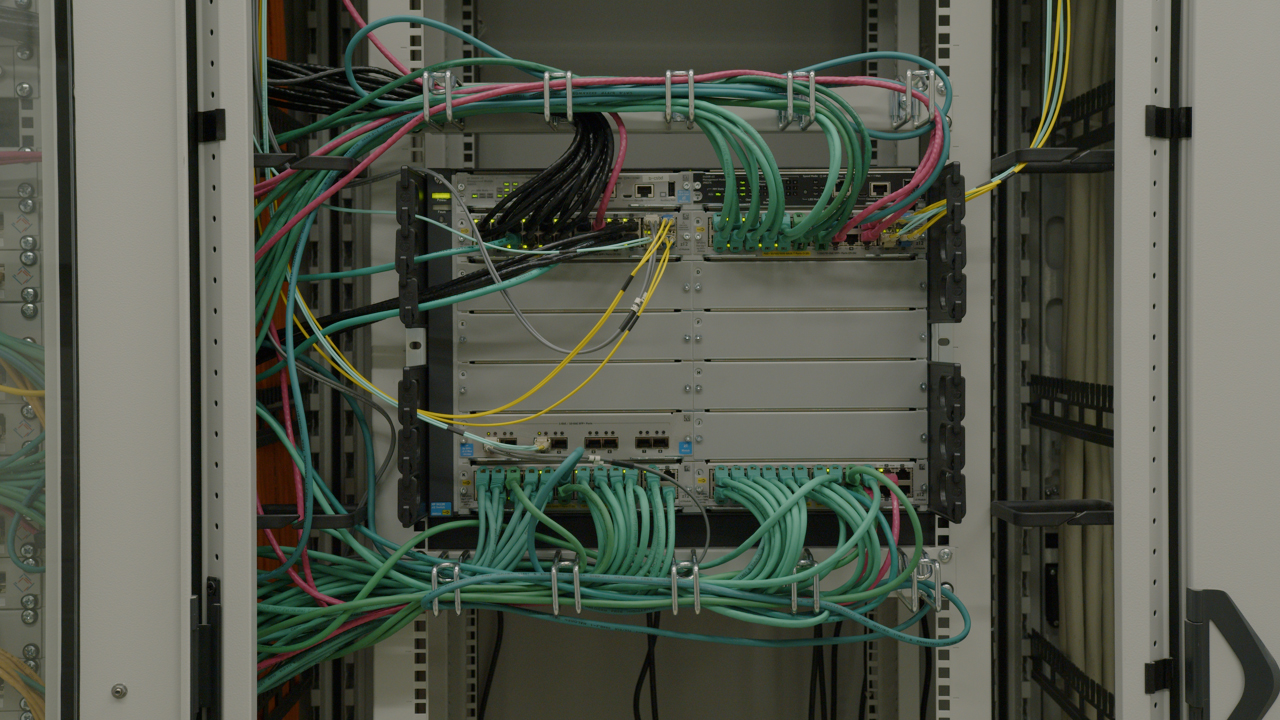

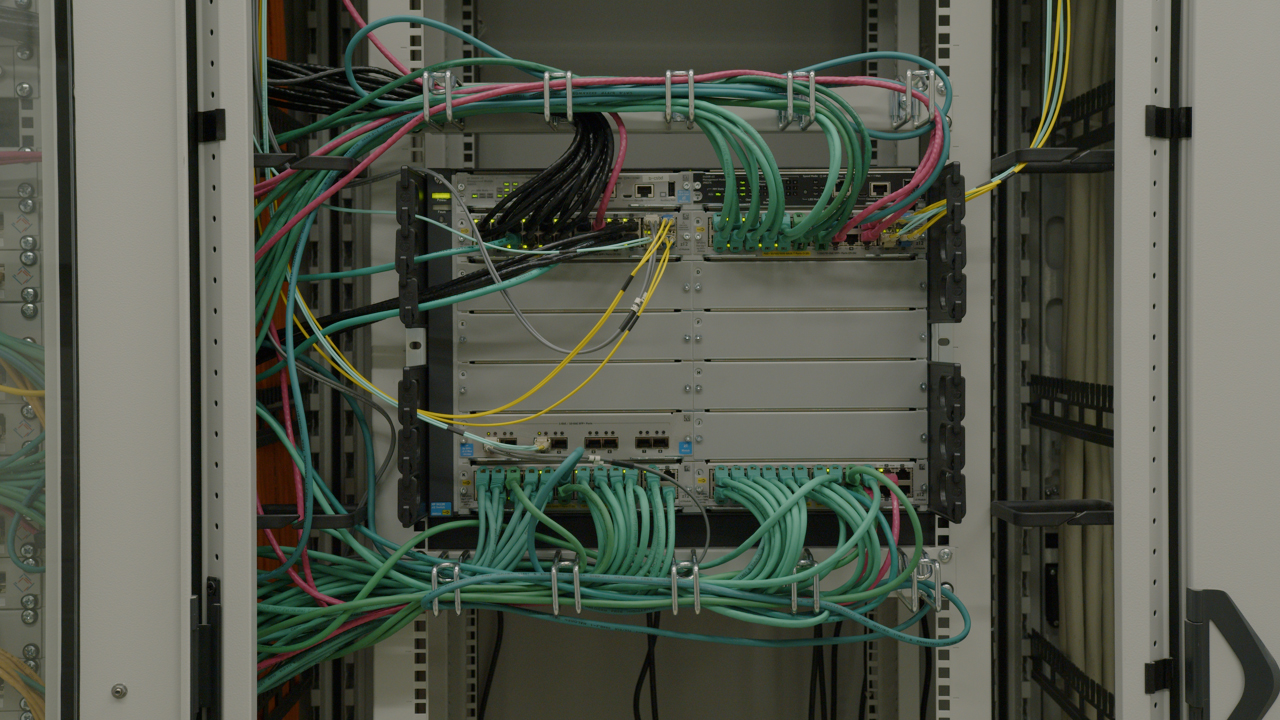

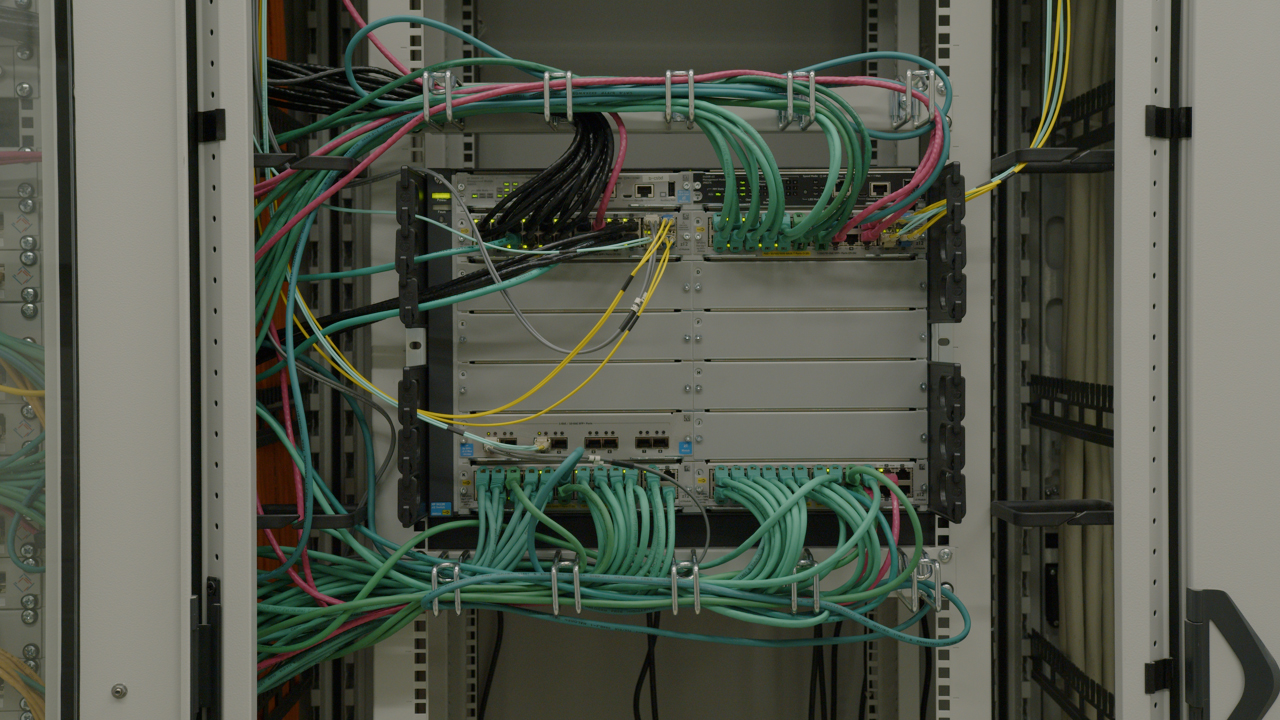

CK - The porosity between species felt most tangible to me when looking at all of these different environments collectively – from a petri dish in the lab, to pet shops, to server farms, to rivers and rice paddies in northern India. One of the main outcomes of the project is a short film which brings together these many contexts where human and zebrafish worlds collide, showcasing the complex ways in which these two species, our bodies and ecosystems are deeply entangled at planetary scale.

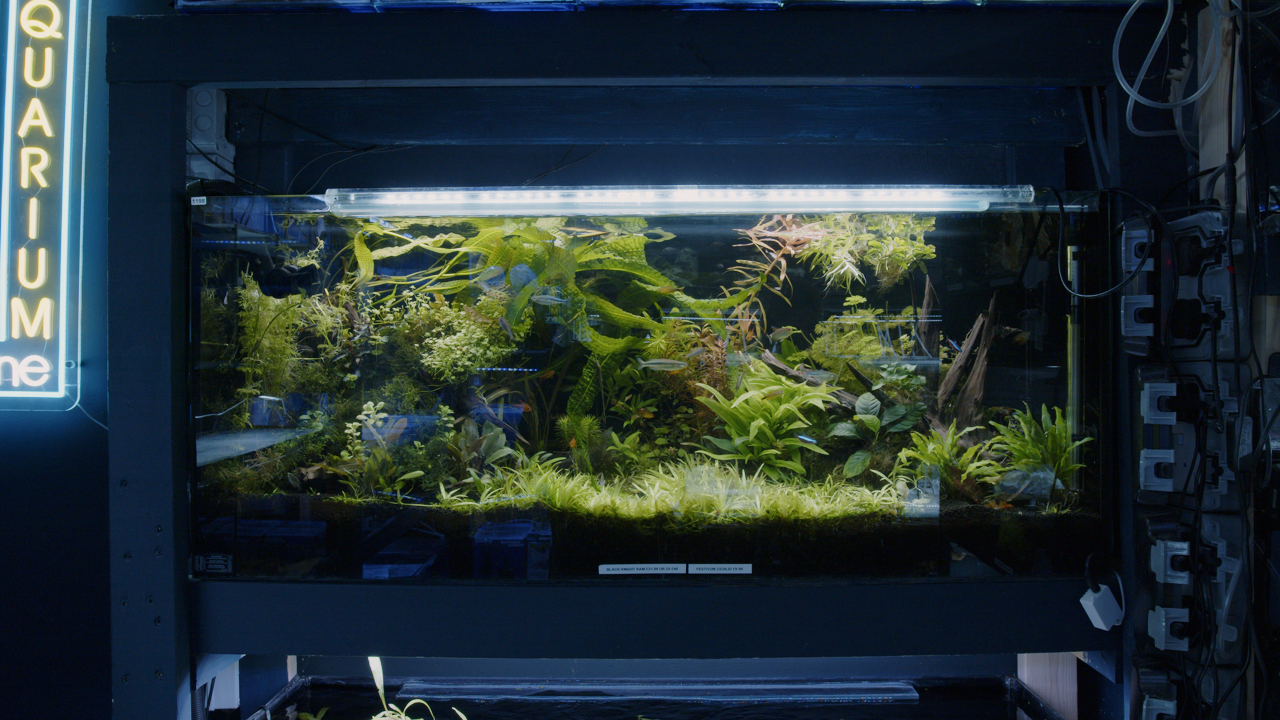

Zebrafish are altering our bodies in indirect but significant ways, given their role in biomedical research. Human clinical trials for treatments that repair retinal tissue are currently under way, for example, thanks to what has been learned from fish. Simultaneously, humans are drastically reconfiguring the life worlds of this small fish – with more zebrafish living in laboratories across the world than in the wild. They are one of the most popular species in the global aquarium trade, living as companions in domestic spaces, and all the while anthropogenic activity and climate change are disrupting their remaining ecosystems in the wild.

As part of my research, I spoke with one of the few ecologists who study zebrafish in the wild across the Indian subcontinent. He described the cultural significance of these small fish, and how Indian farmers have lived alongside them for thousands of years – welcoming them into their flooded rice paddies, as they help to maintain an ecological balance by eating insects and regulating carbon flux. This is the most reciprocal relationship I encountered as part of my fieldwork. Most other contexts, although porous in their boundaries between the two species, are dominated by our anthropocentric desires.

I suppose my hope is that, by confronting these deep connections – spanning millions of years, from our shared evolutionary history to the present – and by foregrounding a kind of intimacy between species that stretches from microscopic to planetary scales, the film might, in some small way, contribute to the emergence of a different cultural view of the zebrafish — one which acknowledges its significance, and where this porosity between species perhaps can become more reciprocal.

JF - Speculating 100 years ahead, the project imagines regenerative human hearts and human tissues grown from fish cells. Do you see these futures as acts of care or extraction?

CK - Current scientific research is actively studying the regenerative abilities of zebrafish, in the hopes of learning from the fish and bringing this into the human body. This type of research could give rise to biomedical treatments which allow us to repair our hearts, retinas, spinal cords, and other organs.

The idea of human tissue grown from fish cells, too, is described on the website of an existing research group. Apparently if the physical laws at play in tissue formation are understood, then they can also be manipulated – meaning that it would be hypothetically possible to grow fish cells into the shape of human tissue. So these are not distant speculations, but rather research that is already happening in the here and now!

Currently these efforts are largely extractive – driven by a desire to heal our bodies, learn about our biology, and advance human knowledge. Zebrafish are not benefiting from this.

Looking to the future, these research efforts point to a world where the boundaries between the bodies of humans and fish will only continue to blur. For me, this trajectory is an opportunity to insert myself as an artist, to consider potential interspecies futures that move beyond extraction.

I’m interested in building literacy around how labs, ecologies, and culture intersect, and raising important philosophical and ethical questions on the potential planetary implications of molecular scale research – bringing into dialogue our often extractive relationships to non-human worlds, and possibilities to unsettle them. How might zebrafish alter perceptions of our own bodies, for example? Do entrenched ideas of human exceptionalism, of us as somehow separate from and superior to other life forms, become harder to uphold in a world where we’re learning from fish, using them as models for our own body, and searching for foundational principles connecting all life?

What kinds of cultural shifts might this produce, and how might this contribute to a necessary recalibration in relationships between human and non-human worlds in the context of the climate crisis? Could potential positive transformations emerge from an interspecies approach to research & technology, and what might this look like? These are the types of questions and speculations I have been thinking about with the project.

JF - Much of your practice pushes the boundaries of human perception, exploring molecular processes, deep time and non-human sensing. Where do you see imagination becoming a necessary tool for ecological responsibility?

CK - Much of the world is beyond the reach of humans. I feel that is important to acknowledge in conversations around ecological responsibility.

Despite rapid scientific advances, we’re surrounded by such vastly complex ecologies and Earth systems that many of them we are simply not able to model, understand, compute, or predict – despite our best efforts. Our senses, too, limit our grasp on the world around us. Geological timescales, the life worlds of non-humans, microscopic events, and planetary processes remain largely beyond our reach. We rely on technologies and our imagination to steal small glimpses of these worlds.

The role of an artist becomes interesting to consider here, particularly when working at intersections between art and science. As an artist, I am not constrained by the same rigour as scientific disciplines – I have the space to veer into the unknowns, and seek out these limitations set by our bodies and minds. Alongside science, I see fiction and imagination as important cultural tools that can alter the way we understand the world and our place within it.

Alongside the short film, a second project outcome is a speculative 3D anatomical model which looks to the distant past – making tangible the heart of the last common ancestor between humans and zebrafish, 450 million years ago. Due to insufficient fossil evidence, this ancient heart is an organ that – from a scientific perspective – is relegated to the space of hypotheticals and speculation. It has been interesting to consider my role here, and the possibility of working creatively with computational tools from palaeontology, veering into the realms of fiction, for an attempt at making our shared evolutionary history tangible.

JF - There Is No Such Thing as a Fish explores the role of Zebrafish as model organisms acting as proxies for human bodies and futures, at what moments in the research has this substitution felt particularly uncanny? Has it altered your perception of your own body in any way?

CK - Much of the past year I have spent learning about zebrafish and the commonalities between our bodies – between humans and this small tropical fish. We share around 70% of our genome with zebrafish. We evolved from a common ancestor, an ancient fish that swam the Cambrian seas roughly 450 million years ago. This evolutionary connection means that many of the traits we associate with being uniquely human have actually evolved from fish. Consciousness first evolved from fish. Our capacity for emotions, memory, and learning, too. In the embryonic stage, humans briefly develop gill arches. We have hiccups because of lingering neural circuits that coordinate breathing in fish.

This shared ancestry is precisely why zebrafish are studied today, in the hope of better understanding our own biology and the common principles of life – making them one of the most widely used model organisms in scientific research.

Spending so much time thinking about this small fish, and about how much we have in common, has undoubtedly shifted something in my thinking. It’s pretty amazing – and strangely comforting – to think of my body as a part of this long evolutionary timeline. Worms and sea sponges and jellyfish and all the other beings that came before us – parts of them are still here now.

Another thing that has stuck with me is that, from a strictly taxonomical perspective, apparently ‘fish’ is not a valid biological group, unless it contains all descendants of a common ancestor – unless it includes humans, too. Arguably there is either no such thing as a fish, or we are all fish. I quite like the idea that I am more fish-like than I realised – that my body is less singular, less exceptional, and more continuous with the rest of life than I gave it credit for.

JF - What has the project revealed about the limits of scientific abstraction, and where does the controlled logic of the laboratory come into friction with the unruly, messy realities of lived ecological entanglements?

CK - There Is No Such Thing as a Fish came out of a year-long art-science residency (S+T+ARTS Ec(h)o) working together with scientists from the Physics of Life group across the TUD Dresden University of Technology, the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG), and the Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden (CRTD).

Physics of Life is a relatively new field, driven by a search for the fundamental biological principles, physical laws, and mathematical equations that govern life. In other words, researchers are interested in whether life can be explained through the laws of physics – and, ultimately, whether it is possible to build computational models of living biological systems.

One of the reasons I was drawn to this field of research is a long-standing interest in models. It is a recurring theme across many of my projects: a desire to contend with the role of conceptual, biological, physical, and computational models – and their limitations.

Models are, by definition and by design, abstracted representations of the thing which they seek to describe. They play a hugely important scientific and socio-cultural role, with their ability to make complex systems tangible. In the context of climate science, for example, models are perhaps the only chance to move beyond localised observations, to produce a picture of and make predictions for the planet as a whole.

But the authority of models can also become persuasive in a way that exceeds their scope. The risk is a shift from using models as tools, to imagining that reality itself is fundamentally model-like: computable, predictable, and optimisable. It’s a perspective that disregards the vast and messy complexities of Earth systems, which in fact remain far beyond reach of our current knowledge and computational capacities.

Thinking about models and scientific abstraction specifically in the context of this current project: first, there is the zebrafish itself – used as a living model for the human body. While this substitution is scientifically productive, there is something instinctively confronting about it. What does it mean to use the body of one species as a model or stand-in for another – especially in the face of profound physiological differences between humans and fish?

The fish facilities in the laboratory, meanwhile, are a rather uncanny model for the zebrafish’s ecosystems in the wild: with carefully regulated water temperatures and oxygen levels; breeding grounds simulated in sloped plastic dishes; and an environment sanitised of pathogens and predators. Ultimately, it is a highly controlled, artificial world with very little in common with the zebrafish’s wild habitats.

Simultaneously, researchers are attempting to construct computational models of the fish — a model of the model – so that perhaps one day live fish are no longer needed for scientific research. These are some of the multiple layers of abstraction I have come across, each one a step further removed from the original.

And yet even the laboratory fish are no longer quite “original”. Bred for generations in controlled environments, their genomes have diverged from wild populations. The pervasiveness of transgenic lines – fish engineered for particular research purposes – only amplifies this genetic divide. So even as a model to understand its own species in the wild, lab zebrafish are not particularly representative.

Accuracy to ‘the real thing,’ I have come to realise, is not exactly the aim. What is required from models in scientific research is a stable, controllable set of variables – an environment that can be regulated and reproduced. The abstract model is therefore, quite intentionally, untethered from messy ecological realities, and becomes the primary object of study.

What I am hoping to draw out with my project is the visceral weirdness of some of these relationships and layered substitutions – and bring the unruly messiness of ecological entanglements back into focus.

JF - Your fieldwork moves from petri dishes to rivers in northern India, from domestic aquariums to industrial infrastructures. How have these sites altered your perception of scale and intimacy, and where have you felt the boundary between species becoming most porous?

CK - The porosity between species felt most tangible to me when looking at all of these different environments collectively – from a petri dish in the lab, to pet shops, to server farms, to rivers and rice paddies in northern India. One of the main outcomes of the project is a short film which brings together these many contexts where human and zebrafish worlds collide, showcasing the complex ways in which these two species, our bodies and ecosystems are deeply entangled at planetary scale.

Zebrafish are altering our bodies in indirect but significant ways, given their role in biomedical research. Human clinical trials for treatments that repair retinal tissue are currently under way, for example, thanks to what has been learned from fish. Simultaneously, humans are drastically reconfiguring the life worlds of this small fish – with more zebrafish living in laboratories across the world than in the wild. They are one of the most popular species in the global aquarium trade, living as companions in domestic spaces, and all the while anthropogenic activity and climate change are disrupting their remaining ecosystems in the wild.

As part of my research, I spoke with one of the few ecologists who study zebrafish in the wild across the Indian subcontinent. He described the cultural significance of these small fish, and how Indian farmers have lived alongside them for thousands of years – welcoming them into their flooded rice paddies, as they help to maintain an ecological balance by eating insects and regulating carbon flux. This is the most reciprocal relationship I encountered as part of my fieldwork. Most other contexts, although porous in their boundaries between the two species, are dominated by our anthropocentric desires.

I suppose my hope is that, by confronting these deep connections – spanning millions of years, from our shared evolutionary history to the present – and by foregrounding a kind of intimacy between species that stretches from microscopic to planetary scales, the film might, in some small way, contribute to the emergence of a different cultural view of the zebrafish — one which acknowledges its significance, and where this porosity between species perhaps can become more reciprocal.

JF - Speculating 100 years ahead, the project imagines regenerative human hearts and human tissues grown from fish cells. Do you see these futures as acts of care or extraction?

CK - Current scientific research is actively studying the regenerative abilities of zebrafish, in the hopes of learning from the fish and bringing this into the human body. This type of research could give rise to biomedical treatments which allow us to repair our hearts, retinas, spinal cords, and other organs.

The idea of human tissue grown from fish cells, too, is described on the website of an existing research group. Apparently if the physical laws at play in tissue formation are understood, then they can also be manipulated – meaning that it would be hypothetically possible to grow fish cells into the shape of human tissue. So these are not distant speculations, but rather research that is already happening in the here and now!

Currently these efforts are largely extractive – driven by a desire to heal our bodies, learn about our biology, and advance human knowledge. Zebrafish are not benefiting from this.

Looking to the future, these research efforts point to a world where the boundaries between the bodies of humans and fish will only continue to blur. For me, this trajectory is an opportunity to insert myself as an artist, to consider potential interspecies futures that move beyond extraction.

I’m interested in building literacy around how labs, ecologies, and culture intersect, and raising important philosophical and ethical questions on the potential planetary implications of molecular scale research – bringing into dialogue our often extractive relationships to non-human worlds, and possibilities to unsettle them. How might zebrafish alter perceptions of our own bodies, for example? Do entrenched ideas of human exceptionalism, of us as somehow separate from and superior to other life forms, become harder to uphold in a world where we’re learning from fish, using them as models for our own body, and searching for foundational principles connecting all life?

What kinds of cultural shifts might this produce, and how might this contribute to a necessary recalibration in relationships between human and non-human worlds in the context of the climate crisis? Could potential positive transformations emerge from an interspecies approach to research & technology, and what might this look like? These are the types of questions and speculations I have been thinking about with the project.

JF - Much of your practice pushes the boundaries of human perception, exploring molecular processes, deep time and non-human sensing. Where do you see imagination becoming a necessary tool for ecological responsibility?

CK - Much of the world is beyond the reach of humans. I feel that is important to acknowledge in conversations around ecological responsibility.

Despite rapid scientific advances, we’re surrounded by such vastly complex ecologies and Earth systems that many of them we are simply not able to model, understand, compute, or predict – despite our best efforts. Our senses, too, limit our grasp on the world around us. Geological timescales, the life worlds of non-humans, microscopic events, and planetary processes remain largely beyond our reach. We rely on technologies and our imagination to steal small glimpses of these worlds.

The role of an artist becomes interesting to consider here, particularly when working at intersections between art and science. As an artist, I am not constrained by the same rigour as scientific disciplines – I have the space to veer into the unknowns, and seek out these limitations set by our bodies and minds. Alongside science, I see fiction and imagination as important cultural tools that can alter the way we understand the world and our place within it.

Alongside the short film, a second project outcome is a speculative 3D anatomical model which looks to the distant past – making tangible the heart of the last common ancestor between humans and zebrafish, 450 million years ago. Due to insufficient fossil evidence, this ancient heart is an organ that – from a scientific perspective – is relegated to the space of hypotheticals and speculation. It has been interesting to consider my role here, and the possibility of working creatively with computational tools from palaeontology, veering into the realms of fiction, for an attempt at making our shared evolutionary history tangible.

Carolyn Kirschner is a designer and researcher with a background in architecture. Her work explores the growing (and often strange) entanglements of ecologies and machines in the context of the climate crisis. Working with scientific tools, simulation engines, digital fabrication, environmental data and film, she conjures fragments from alternate or expanded worlds—with a particular interest in realms which lie beyond the reach of human senses.

.jpg)

.jpg)

INTERVIEW WITH CAROLYN KIRSCHNER

JF - There Is No Such Thing as a Fish explores the role of Zebrafish as model organisms acting as proxies for human bodies and futures, at what moments in the research has this substitution felt particularly uncanny? Has it altered your perception of your own body in any way?

CK - Much of the past year I have spent learning about zebrafish and the commonalities between our bodies – between humans and this small tropical fish. We share around 70% of our genome with zebrafish. We evolved from a common ancestor, an ancient fish that swam the Cambrian seas roughly 450 million years ago. This evolutionary connection means that many of the traits we associate with being uniquely human have actually evolved from fish. Consciousness first evolved from fish. Our capacity for emotions, memory, and learning, too. In the embryonic stage, humans briefly develop gill arches. We have hiccups because of lingering neural circuits that coordinate breathing in fish.

This shared ancestry is precisely why zebrafish are studied today, in the hope of better understanding our own biology and the common principles of life – making them one of the most widely used model organisms in scientific research.

Spending so much time thinking about this small fish, and about how much we have in common, has undoubtedly shifted something in my thinking. It’s pretty amazing – and strangely comforting – to think of my body as a part of this long evolutionary timeline. Worms and sea sponges and jellyfish and all the other beings that came before us – parts of them are still here now.

Another thing that has stuck with me is that, from a strictly taxonomical perspective, apparently ‘fish’ is not a valid biological group, unless it contains all descendants of a common ancestor – unless it includes humans, too. Arguably there is either no such thing as a fish, or we are all fish. I quite like the idea that I am more fish-like than I realised – that my body is less singular, less exceptional, and more continuous with the rest of life than I gave it credit for.

JF - What has the project revealed about the limits of scientific abstraction, and where does the controlled logic of the laboratory come into friction with the unruly, messy realities of lived ecological entanglements?

CK - There Is No Such Thing as a Fish came out of a year-long art-science residency (S+T+ARTS Ec(h)o) working together with scientists from the Physics of Life group across the TUD Dresden University of Technology, the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG), and the Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden (CRTD).

Physics of Life is a relatively new field, driven by a search for the fundamental biological principles, physical laws, and mathematical equations that govern life. In other words, researchers are interested in whether life can be explained through the laws of physics – and, ultimately, whether it is possible to build computational models of living biological systems.

One of the reasons I was drawn to this field of research is a long-standing interest in models. It is a recurring theme across many of my projects: a desire to contend with the role of conceptual, biological, physical, and computational models – and their limitations.

Models are, by definition and by design, abstracted representations of the thing which they seek to describe. They play a hugely important scientific and socio-cultural role, with their ability to make complex systems tangible. In the context of climate science, for example, models are perhaps the only chance to move beyond localised observations, to produce a picture of and make predictions for the planet as a whole.

But the authority of models can also become persuasive in a way that exceeds their scope. The risk is a shift from using models as tools, to imagining that reality itself is fundamentally model-like: computable, predictable, and optimisable. It’s a perspective that disregards the vast and messy complexities of Earth systems, which in fact remain far beyond reach of our current knowledge and computational capacities.

Thinking about models and scientific abstraction specifically in the context of this current project: first, there is the zebrafish itself – used as a living model for the human body. While this substitution is scientifically productive, there is something instinctively confronting about it. What does it mean to use the body of one species as a model or stand-in for another – especially in the face of profound physiological differences between humans and fish?

The fish facilities in the laboratory, meanwhile, are a rather uncanny model for the zebrafish’s ecosystems in the wild: with carefully regulated water temperatures and oxygen levels; breeding grounds simulated in sloped plastic dishes; and an environment sanitised of pathogens and predators. Ultimately, it is a highly controlled, artificial world with very little in common with the zebrafish’s wild habitats.

Simultaneously, researchers are attempting to construct computational models of the fish — a model of the model – so that perhaps one day live fish are no longer needed for scientific research. These are some of the multiple layers of abstraction I have come across, each one a step further removed from the original.

And yet even the laboratory fish are no longer quite “original”. Bred for generations in controlled environments, their genomes have diverged from wild populations. The pervasiveness of transgenic lines – fish engineered for particular research purposes – only amplifies this genetic divide. So even as a model to understand its own species in the wild, lab zebrafish are not particularly representative.

Accuracy to ‘the real thing,’ I have come to realise, is not exactly the aim. What is required from models in scientific research is a stable, controllable set of variables – an environment that can be regulated and reproduced. The abstract model is therefore, quite intentionally, untethered from messy ecological realities, and becomes the primary object of study.

What I am hoping to draw out with my project is the visceral weirdness of some of these relationships and layered substitutions – and bring the unruly messiness of ecological entanglements back into focus.

JF - Your fieldwork moves from petri dishes to rivers in northern India, from domestic aquariums to industrial infrastructures. How have these sites altered your perception of scale and intimacy, and where have you felt the boundary between species becoming most porous?

CK - The porosity between species felt most tangible to me when looking at all of these different environments collectively – from a petri dish in the lab, to pet shops, to server farms, to rivers and rice paddies in northern India. One of the main outcomes of the project is a short film which brings together these many contexts where human and zebrafish worlds collide, showcasing the complex ways in which these two species, our bodies and ecosystems are deeply entangled at planetary scale.

Zebrafish are altering our bodies in indirect but significant ways, given their role in biomedical research. Human clinical trials for treatments that repair retinal tissue are currently under way, for example, thanks to what has been learned from fish. Simultaneously, humans are drastically reconfiguring the life worlds of this small fish – with more zebrafish living in laboratories across the world than in the wild. They are one of the most popular species in the global aquarium trade, living as companions in domestic spaces, and all the while anthropogenic activity and climate change are disrupting their remaining ecosystems in the wild.

As part of my research, I spoke with one of the few ecologists who study zebrafish in the wild across the Indian subcontinent. He described the cultural significance of these small fish, and how Indian farmers have lived alongside them for thousands of years – welcoming them into their flooded rice paddies, as they help to maintain an ecological balance by eating insects and regulating carbon flux. This is the most reciprocal relationship I encountered as part of my fieldwork. Most other contexts, although porous in their boundaries between the two species, are dominated by our anthropocentric desires.

I suppose my hope is that, by confronting these deep connections – spanning millions of years, from our shared evolutionary history to the present – and by foregrounding a kind of intimacy between species that stretches from microscopic to planetary scales, the film might, in some small way, contribute to the emergence of a different cultural view of the zebrafish — one which acknowledges its significance, and where this porosity between species perhaps can become more reciprocal.

JF - Speculating 100 years ahead, the project imagines regenerative human hearts and human tissues grown from fish cells. Do you see these futures as acts of care or extraction?

CK - Current scientific research is actively studying the regenerative abilities of zebrafish, in the hopes of learning from the fish and bringing this into the human body. This type of research could give rise to biomedical treatments which allow us to repair our hearts, retinas, spinal cords, and other organs.

The idea of human tissue grown from fish cells, too, is described on the website of an existing research group. Apparently if the physical laws at play in tissue formation are understood, then they can also be manipulated – meaning that it would be hypothetically possible to grow fish cells into the shape of human tissue. So these are not distant speculations, but rather research that is already happening in the here and now!

Currently these efforts are largely extractive – driven by a desire to heal our bodies, learn about our biology, and advance human knowledge. Zebrafish are not benefiting from this.

Looking to the future, these research efforts point to a world where the boundaries between the bodies of humans and fish will only continue to blur. For me, this trajectory is an opportunity to insert myself as an artist, to consider potential interspecies futures that move beyond extraction.

I’m interested in building literacy around how labs, ecologies, and culture intersect, and raising important philosophical and ethical questions on the potential planetary implications of molecular scale research – bringing into dialogue our often extractive relationships to non-human worlds, and possibilities to unsettle them. How might zebrafish alter perceptions of our own bodies, for example? Do entrenched ideas of human exceptionalism, of us as somehow separate from and superior to other life forms, become harder to uphold in a world where we’re learning from fish, using them as models for our own body, and searching for foundational principles connecting all life?

What kinds of cultural shifts might this produce, and how might this contribute to a necessary recalibration in relationships between human and non-human worlds in the context of the climate crisis? Could potential positive transformations emerge from an interspecies approach to research & technology, and what might this look like? These are the types of questions and speculations I have been thinking about with the project.

JF - Much of your practice pushes the boundaries of human perception, exploring molecular processes, deep time and non-human sensing. Where do you see imagination becoming a necessary tool for ecological responsibility?

CK - Much of the world is beyond the reach of humans. I feel that is important to acknowledge in conversations around ecological responsibility.

Despite rapid scientific advances, we’re surrounded by such vastly complex ecologies and Earth systems that many of them we are simply not able to model, understand, compute, or predict – despite our best efforts. Our senses, too, limit our grasp on the world around us. Geological timescales, the life worlds of non-humans, microscopic events, and planetary processes remain largely beyond our reach. We rely on technologies and our imagination to steal small glimpses of these worlds.

The role of an artist becomes interesting to consider here, particularly when working at intersections between art and science. As an artist, I am not constrained by the same rigour as scientific disciplines – I have the space to veer into the unknowns, and seek out these limitations set by our bodies and minds. Alongside science, I see fiction and imagination as important cultural tools that can alter the way we understand the world and our place within it.

Alongside the short film, a second project outcome is a speculative 3D anatomical model which looks to the distant past – making tangible the heart of the last common ancestor between humans and zebrafish, 450 million years ago. Due to insufficient fossil evidence, this ancient heart is an organ that – from a scientific perspective – is relegated to the space of hypotheticals and speculation. It has been interesting to consider my role here, and the possibility of working creatively with computational tools from palaeontology, veering into the realms of fiction, for an attempt at making our shared evolutionary history tangible.

JF - There Is No Such Thing as a Fish explores the role of Zebrafish as model organisms acting as proxies for human bodies and futures, at what moments in the research has this substitution felt particularly uncanny? Has it altered your perception of your own body in any way?

CK - Much of the past year I have spent learning about zebrafish and the commonalities between our bodies – between humans and this small tropical fish. We share around 70% of our genome with zebrafish. We evolved from a common ancestor, an ancient fish that swam the Cambrian seas roughly 450 million years ago. This evolutionary connection means that many of the traits we associate with being uniquely human have actually evolved from fish. Consciousness first evolved from fish. Our capacity for emotions, memory, and learning, too. In the embryonic stage, humans briefly develop gill arches. We have hiccups because of lingering neural circuits that coordinate breathing in fish.

This shared ancestry is precisely why zebrafish are studied today, in the hope of better understanding our own biology and the common principles of life – making them one of the most widely used model organisms in scientific research.

Spending so much time thinking about this small fish, and about how much we have in common, has undoubtedly shifted something in my thinking. It’s pretty amazing – and strangely comforting – to think of my body as a part of this long evolutionary timeline. Worms and sea sponges and jellyfish and all the other beings that came before us – parts of them are still here now.

Another thing that has stuck with me is that, from a strictly taxonomical perspective, apparently ‘fish’ is not a valid biological group, unless it contains all descendants of a common ancestor – unless it includes humans, too. Arguably there is either no such thing as a fish, or we are all fish. I quite like the idea that I am more fish-like than I realised – that my body is less singular, less exceptional, and more continuous with the rest of life than I gave it credit for.

JF - What has the project revealed about the limits of scientific abstraction, and where does the controlled logic of the laboratory come into friction with the unruly, messy realities of lived ecological entanglements?

CK - There Is No Such Thing as a Fish came out of a year-long art-science residency (S+T+ARTS Ec(h)o) working together with scientists from the Physics of Life group across the TUD Dresden University of Technology, the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG), and the Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden (CRTD).

Physics of Life is a relatively new field, driven by a search for the fundamental biological principles, physical laws, and mathematical equations that govern life. In other words, researchers are interested in whether life can be explained through the laws of physics – and, ultimately, whether it is possible to build computational models of living biological systems.

One of the reasons I was drawn to this field of research is a long-standing interest in models. It is a recurring theme across many of my projects: a desire to contend with the role of conceptual, biological, physical, and computational models – and their limitations.

Models are, by definition and by design, abstracted representations of the thing which they seek to describe. They play a hugely important scientific and socio-cultural role, with their ability to make complex systems tangible. In the context of climate science, for example, models are perhaps the only chance to move beyond localised observations, to produce a picture of and make predictions for the planet as a whole.

But the authority of models can also become persuasive in a way that exceeds their scope. The risk is a shift from using models as tools, to imagining that reality itself is fundamentally model-like: computable, predictable, and optimisable. It’s a perspective that disregards the vast and messy complexities of Earth systems, which in fact remain far beyond reach of our current knowledge and computational capacities.

Thinking about models and scientific abstraction specifically in the context of this current project: first, there is the zebrafish itself – used as a living model for the human body. While this substitution is scientifically productive, there is something instinctively confronting about it. What does it mean to use the body of one species as a model or stand-in for another – especially in the face of profound physiological differences between humans and fish?

The fish facilities in the laboratory, meanwhile, are a rather uncanny model for the zebrafish’s ecosystems in the wild: with carefully regulated water temperatures and oxygen levels; breeding grounds simulated in sloped plastic dishes; and an environment sanitised of pathogens and predators. Ultimately, it is a highly controlled, artificial world with very little in common with the zebrafish’s wild habitats.

Simultaneously, researchers are attempting to construct computational models of the fish — a model of the model – so that perhaps one day live fish are no longer needed for scientific research. These are some of the multiple layers of abstraction I have come across, each one a step further removed from the original.

And yet even the laboratory fish are no longer quite “original”. Bred for generations in controlled environments, their genomes have diverged from wild populations. The pervasiveness of transgenic lines – fish engineered for particular research purposes – only amplifies this genetic divide. So even as a model to understand its own species in the wild, lab zebrafish are not particularly representative.

Accuracy to ‘the real thing,’ I have come to realise, is not exactly the aim. What is required from models in scientific research is a stable, controllable set of variables – an environment that can be regulated and reproduced. The abstract model is therefore, quite intentionally, untethered from messy ecological realities, and becomes the primary object of study.

What I am hoping to draw out with my project is the visceral weirdness of some of these relationships and layered substitutions – and bring the unruly messiness of ecological entanglements back into focus.

JF - Your fieldwork moves from petri dishes to rivers in northern India, from domestic aquariums to industrial infrastructures. How have these sites altered your perception of scale and intimacy, and where have you felt the boundary between species becoming most porous?

CK - The porosity between species felt most tangible to me when looking at all of these different environments collectively – from a petri dish in the lab, to pet shops, to server farms, to rivers and rice paddies in northern India. One of the main outcomes of the project is a short film which brings together these many contexts where human and zebrafish worlds collide, showcasing the complex ways in which these two species, our bodies and ecosystems are deeply entangled at planetary scale.

Zebrafish are altering our bodies in indirect but significant ways, given their role in biomedical research. Human clinical trials for treatments that repair retinal tissue are currently under way, for example, thanks to what has been learned from fish. Simultaneously, humans are drastically reconfiguring the life worlds of this small fish – with more zebrafish living in laboratories across the world than in the wild. They are one of the most popular species in the global aquarium trade, living as companions in domestic spaces, and all the while anthropogenic activity and climate change are disrupting their remaining ecosystems in the wild.

As part of my research, I spoke with one of the few ecologists who study zebrafish in the wild across the Indian subcontinent. He described the cultural significance of these small fish, and how Indian farmers have lived alongside them for thousands of years – welcoming them into their flooded rice paddies, as they help to maintain an ecological balance by eating insects and regulating carbon flux. This is the most reciprocal relationship I encountered as part of my fieldwork. Most other contexts, although porous in their boundaries between the two species, are dominated by our anthropocentric desires.

I suppose my hope is that, by confronting these deep connections – spanning millions of years, from our shared evolutionary history to the present – and by foregrounding a kind of intimacy between species that stretches from microscopic to planetary scales, the film might, in some small way, contribute to the emergence of a different cultural view of the zebrafish — one which acknowledges its significance, and where this porosity between species perhaps can become more reciprocal.

JF - Speculating 100 years ahead, the project imagines regenerative human hearts and human tissues grown from fish cells. Do you see these futures as acts of care or extraction?

CK - Current scientific research is actively studying the regenerative abilities of zebrafish, in the hopes of learning from the fish and bringing this into the human body. This type of research could give rise to biomedical treatments which allow us to repair our hearts, retinas, spinal cords, and other organs.

The idea of human tissue grown from fish cells, too, is described on the website of an existing research group. Apparently if the physical laws at play in tissue formation are understood, then they can also be manipulated – meaning that it would be hypothetically possible to grow fish cells into the shape of human tissue. So these are not distant speculations, but rather research that is already happening in the here and now!

Currently these efforts are largely extractive – driven by a desire to heal our bodies, learn about our biology, and advance human knowledge. Zebrafish are not benefiting from this.

Looking to the future, these research efforts point to a world where the boundaries between the bodies of humans and fish will only continue to blur. For me, this trajectory is an opportunity to insert myself as an artist, to consider potential interspecies futures that move beyond extraction.

I’m interested in building literacy around how labs, ecologies, and culture intersect, and raising important philosophical and ethical questions on the potential planetary implications of molecular scale research – bringing into dialogue our often extractive relationships to non-human worlds, and possibilities to unsettle them. How might zebrafish alter perceptions of our own bodies, for example? Do entrenched ideas of human exceptionalism, of us as somehow separate from and superior to other life forms, become harder to uphold in a world where we’re learning from fish, using them as models for our own body, and searching for foundational principles connecting all life?

What kinds of cultural shifts might this produce, and how might this contribute to a necessary recalibration in relationships between human and non-human worlds in the context of the climate crisis? Could potential positive transformations emerge from an interspecies approach to research & technology, and what might this look like? These are the types of questions and speculations I have been thinking about with the project.

JF - Much of your practice pushes the boundaries of human perception, exploring molecular processes, deep time and non-human sensing. Where do you see imagination becoming a necessary tool for ecological responsibility?

CK - Much of the world is beyond the reach of humans. I feel that is important to acknowledge in conversations around ecological responsibility.

Despite rapid scientific advances, we’re surrounded by such vastly complex ecologies and Earth systems that many of them we are simply not able to model, understand, compute, or predict – despite our best efforts. Our senses, too, limit our grasp on the world around us. Geological timescales, the life worlds of non-humans, microscopic events, and planetary processes remain largely beyond our reach. We rely on technologies and our imagination to steal small glimpses of these worlds.

The role of an artist becomes interesting to consider here, particularly when working at intersections between art and science. As an artist, I am not constrained by the same rigour as scientific disciplines – I have the space to veer into the unknowns, and seek out these limitations set by our bodies and minds. Alongside science, I see fiction and imagination as important cultural tools that can alter the way we understand the world and our place within it.

Alongside the short film, a second project outcome is a speculative 3D anatomical model which looks to the distant past – making tangible the heart of the last common ancestor between humans and zebrafish, 450 million years ago. Due to insufficient fossil evidence, this ancient heart is an organ that – from a scientific perspective – is relegated to the space of hypotheticals and speculation. It has been interesting to consider my role here, and the possibility of working creatively with computational tools from palaeontology, veering into the realms of fiction, for an attempt at making our shared evolutionary history tangible.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Carolyn Kirschner is a designer and researcher with a background in architecture. Her work explores the growing (and often strange) entanglements of ecologies and machines in the context of the climate crisis. Working with scientific tools, simulation engines, digital fabrication, environmental data and film, she conjures fragments from alternate or expanded worlds—with a particular interest in realms which lie beyond the reach of human senses.

INTERVIEW WITH CAROLYN KIRSCHNER

JF - There Is No Such Thing as a Fish explores the role of Zebrafish as model organisms acting as proxies for human bodies and futures, at what moments in the research has this substitution felt particularly uncanny? Has it altered your perception of your own body in any way?

CK - Much of the past year I have spent learning about zebrafish and the commonalities between our bodies – between humans and this small tropical fish. We share around 70% of our genome with zebrafish. We evolved from a common ancestor, an ancient fish that swam the Cambrian seas roughly 450 million years ago. This evolutionary connection means that many of the traits we associate with being uniquely human have actually evolved from fish. Consciousness first evolved from fish. Our capacity for emotions, memory, and learning, too. In the embryonic stage, humans briefly develop gill arches. We have hiccups because of lingering neural circuits that coordinate breathing in fish.

This shared ancestry is precisely why zebrafish are studied today, in the hope of better understanding our own biology and the common principles of life – making them one of the most widely used model organisms in scientific research.

Spending so much time thinking about this small fish, and about how much we have in common, has undoubtedly shifted something in my thinking. It’s pretty amazing – and strangely comforting – to think of my body as a part of this long evolutionary timeline. Worms and sea sponges and jellyfish and all the other beings that came before us – parts of them are still here now.

Another thing that has stuck with me is that, from a strictly taxonomical perspective, apparently ‘fish’ is not a valid biological group, unless it contains all descendants of a common ancestor – unless it includes humans, too. Arguably there is either no such thing as a fish, or we are all fish. I quite like the idea that I am more fish-like than I realised – that my body is less singular, less exceptional, and more continuous with the rest of life than I gave it credit for.

JF - What has the project revealed about the limits of scientific abstraction, and where does the controlled logic of the laboratory come into friction with the unruly, messy realities of lived ecological entanglements?

CK - There Is No Such Thing as a Fish came out of a year-long art-science residency (S+T+ARTS Ec(h)o) working together with scientists from the Physics of Life group across the TUD Dresden University of Technology, the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG), and the Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden (CRTD).

Physics of Life is a relatively new field, driven by a search for the fundamental biological principles, physical laws, and mathematical equations that govern life. In other words, researchers are interested in whether life can be explained through the laws of physics – and, ultimately, whether it is possible to build computational models of living biological systems.

One of the reasons I was drawn to this field of research is a long-standing interest in models. It is a recurring theme across many of my projects: a desire to contend with the role of conceptual, biological, physical, and computational models – and their limitations.

Models are, by definition and by design, abstracted representations of the thing which they seek to describe. They play a hugely important scientific and socio-cultural role, with their ability to make complex systems tangible. In the context of climate science, for example, models are perhaps the only chance to move beyond localised observations, to produce a picture of and make predictions for the planet as a whole.

But the authority of models can also become persuasive in a way that exceeds their scope. The risk is a shift from using models as tools, to imagining that reality itself is fundamentally model-like: computable, predictable, and optimisable. It’s a perspective that disregards the vast and messy complexities of Earth systems, which in fact remain far beyond reach of our current knowledge and computational capacities.

Thinking about models and scientific abstraction specifically in the context of this current project: first, there is the zebrafish itself – used as a living model for the human body. While this substitution is scientifically productive, there is something instinctively confronting about it. What does it mean to use the body of one species as a model or stand-in for another – especially in the face of profound physiological differences between humans and fish?

The fish facilities in the laboratory, meanwhile, are a rather uncanny model for the zebrafish’s ecosystems in the wild: with carefully regulated water temperatures and oxygen levels; breeding grounds simulated in sloped plastic dishes; and an environment sanitised of pathogens and predators. Ultimately, it is a highly controlled, artificial world with very little in common with the zebrafish’s wild habitats.

Simultaneously, researchers are attempting to construct computational models of the fish — a model of the model – so that perhaps one day live fish are no longer needed for scientific research. These are some of the multiple layers of abstraction I have come across, each one a step further removed from the original.

And yet even the laboratory fish are no longer quite “original”. Bred for generations in controlled environments, their genomes have diverged from wild populations. The pervasiveness of transgenic lines – fish engineered for particular research purposes – only amplifies this genetic divide. So even as a model to understand its own species in the wild, lab zebrafish are not particularly representative.

Accuracy to ‘the real thing,’ I have come to realise, is not exactly the aim. What is required from models in scientific research is a stable, controllable set of variables – an environment that can be regulated and reproduced. The abstract model is therefore, quite intentionally, untethered from messy ecological realities, and becomes the primary object of study.

What I am hoping to draw out with my project is the visceral weirdness of some of these relationships and layered substitutions – and bring the unruly messiness of ecological entanglements back into focus.

JF - Your fieldwork moves from petri dishes to rivers in northern India, from domestic aquariums to industrial infrastructures. How have these sites altered your perception of scale and intimacy, and where have you felt the boundary between species becoming most porous?

CK - The porosity between species felt most tangible to me when looking at all of these different environments collectively – from a petri dish in the lab, to pet shops, to server farms, to rivers and rice paddies in northern India. One of the main outcomes of the project is a short film which brings together these many contexts where human and zebrafish worlds collide, showcasing the complex ways in which these two species, our bodies and ecosystems are deeply entangled at planetary scale.

Zebrafish are altering our bodies in indirect but significant ways, given their role in biomedical research. Human clinical trials for treatments that repair retinal tissue are currently under way, for example, thanks to what has been learned from fish. Simultaneously, humans are drastically reconfiguring the life worlds of this small fish – with more zebrafish living in laboratories across the world than in the wild. They are one of the most popular species in the global aquarium trade, living as companions in domestic spaces, and all the while anthropogenic activity and climate change are disrupting their remaining ecosystems in the wild.

As part of my research, I spoke with one of the few ecologists who study zebrafish in the wild across the Indian subcontinent. He described the cultural significance of these small fish, and how Indian farmers have lived alongside them for thousands of years – welcoming them into their flooded rice paddies, as they help to maintain an ecological balance by eating insects and regulating carbon flux. This is the most reciprocal relationship I encountered as part of my fieldwork. Most other contexts, although porous in their boundaries between the two species, are dominated by our anthropocentric desires.

I suppose my hope is that, by confronting these deep connections – spanning millions of years, from our shared evolutionary history to the present – and by foregrounding a kind of intimacy between species that stretches from microscopic to planetary scales, the film might, in some small way, contribute to the emergence of a different cultural view of the zebrafish — one which acknowledges its significance, and where this porosity between species perhaps can become more reciprocal.

JF - Speculating 100 years ahead, the project imagines regenerative human hearts and human tissues grown from fish cells. Do you see these futures as acts of care or extraction?

CK - Current scientific research is actively studying the regenerative abilities of zebrafish, in the hopes of learning from the fish and bringing this into the human body. This type of research could give rise to biomedical treatments which allow us to repair our hearts, retinas, spinal cords, and other organs.

The idea of human tissue grown from fish cells, too, is described on the website of an existing research group. Apparently if the physical laws at play in tissue formation are understood, then they can also be manipulated – meaning that it would be hypothetically possible to grow fish cells into the shape of human tissue. So these are not distant speculations, but rather research that is already happening in the here and now!

Currently these efforts are largely extractive – driven by a desire to heal our bodies, learn about our biology, and advance human knowledge. Zebrafish are not benefiting from this.

Looking to the future, these research efforts point to a world where the boundaries between the bodies of humans and fish will only continue to blur. For me, this trajectory is an opportunity to insert myself as an artist, to consider potential interspecies futures that move beyond extraction.

I’m interested in building literacy around how labs, ecologies, and culture intersect, and raising important philosophical and ethical questions on the potential planetary implications of molecular scale research – bringing into dialogue our often extractive relationships to non-human worlds, and possibilities to unsettle them. How might zebrafish alter perceptions of our own bodies, for example? Do entrenched ideas of human exceptionalism, of us as somehow separate from and superior to other life forms, become harder to uphold in a world where we’re learning from fish, using them as models for our own body, and searching for foundational principles connecting all life?

What kinds of cultural shifts might this produce, and how might this contribute to a necessary recalibration in relationships between human and non-human worlds in the context of the climate crisis? Could potential positive transformations emerge from an interspecies approach to research & technology, and what might this look like? These are the types of questions and speculations I have been thinking about with the project.

JF - Much of your practice pushes the boundaries of human perception, exploring molecular processes, deep time and non-human sensing. Where do you see imagination becoming a necessary tool for ecological responsibility?

CK - Much of the world is beyond the reach of humans. I feel that is important to acknowledge in conversations around ecological responsibility.

Despite rapid scientific advances, we’re surrounded by such vastly complex ecologies and Earth systems that many of them we are simply not able to model, understand, compute, or predict – despite our best efforts. Our senses, too, limit our grasp on the world around us. Geological timescales, the life worlds of non-humans, microscopic events, and planetary processes remain largely beyond our reach. We rely on technologies and our imagination to steal small glimpses of these worlds.

The role of an artist becomes interesting to consider here, particularly when working at intersections between art and science. As an artist, I am not constrained by the same rigour as scientific disciplines – I have the space to veer into the unknowns, and seek out these limitations set by our bodies and minds. Alongside science, I see fiction and imagination as important cultural tools that can alter the way we understand the world and our place within it.

Alongside the short film, a second project outcome is a speculative 3D anatomical model which looks to the distant past – making tangible the heart of the last common ancestor between humans and zebrafish, 450 million years ago. Due to insufficient fossil evidence, this ancient heart is an organ that – from a scientific perspective – is relegated to the space of hypotheticals and speculation. It has been interesting to consider my role here, and the possibility of working creatively with computational tools from palaeontology, veering into the realms of fiction, for an attempt at making our shared evolutionary history tangible.

JF - There Is No Such Thing as a Fish explores the role of Zebrafish as model organisms acting as proxies for human bodies and futures, at what moments in the research has this substitution felt particularly uncanny? Has it altered your perception of your own body in any way?

CK - Much of the past year I have spent learning about zebrafish and the commonalities between our bodies – between humans and this small tropical fish. We share around 70% of our genome with zebrafish. We evolved from a common ancestor, an ancient fish that swam the Cambrian seas roughly 450 million years ago. This evolutionary connection means that many of the traits we associate with being uniquely human have actually evolved from fish. Consciousness first evolved from fish. Our capacity for emotions, memory, and learning, too. In the embryonic stage, humans briefly develop gill arches. We have hiccups because of lingering neural circuits that coordinate breathing in fish.

This shared ancestry is precisely why zebrafish are studied today, in the hope of better understanding our own biology and the common principles of life – making them one of the most widely used model organisms in scientific research.

Spending so much time thinking about this small fish, and about how much we have in common, has undoubtedly shifted something in my thinking. It’s pretty amazing – and strangely comforting – to think of my body as a part of this long evolutionary timeline. Worms and sea sponges and jellyfish and all the other beings that came before us – parts of them are still here now.

Another thing that has stuck with me is that, from a strictly taxonomical perspective, apparently ‘fish’ is not a valid biological group, unless it contains all descendants of a common ancestor – unless it includes humans, too. Arguably there is either no such thing as a fish, or we are all fish. I quite like the idea that I am more fish-like than I realised – that my body is less singular, less exceptional, and more continuous with the rest of life than I gave it credit for.

JF - What has the project revealed about the limits of scientific abstraction, and where does the controlled logic of the laboratory come into friction with the unruly, messy realities of lived ecological entanglements?

CK - There Is No Such Thing as a Fish came out of a year-long art-science residency (S+T+ARTS Ec(h)o) working together with scientists from the Physics of Life group across the TUD Dresden University of Technology, the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG), and the Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden (CRTD).

Physics of Life is a relatively new field, driven by a search for the fundamental biological principles, physical laws, and mathematical equations that govern life. In other words, researchers are interested in whether life can be explained through the laws of physics – and, ultimately, whether it is possible to build computational models of living biological systems.

One of the reasons I was drawn to this field of research is a long-standing interest in models. It is a recurring theme across many of my projects: a desire to contend with the role of conceptual, biological, physical, and computational models – and their limitations.

Models are, by definition and by design, abstracted representations of the thing which they seek to describe. They play a hugely important scientific and socio-cultural role, with their ability to make complex systems tangible. In the context of climate science, for example, models are perhaps the only chance to move beyond localised observations, to produce a picture of and make predictions for the planet as a whole.

But the authority of models can also become persuasive in a way that exceeds their scope. The risk is a shift from using models as tools, to imagining that reality itself is fundamentally model-like: computable, predictable, and optimisable. It’s a perspective that disregards the vast and messy complexities of Earth systems, which in fact remain far beyond reach of our current knowledge and computational capacities.

Thinking about models and scientific abstraction specifically in the context of this current project: first, there is the zebrafish itself – used as a living model for the human body. While this substitution is scientifically productive, there is something instinctively confronting about it. What does it mean to use the body of one species as a model or stand-in for another – especially in the face of profound physiological differences between humans and fish?

The fish facilities in the laboratory, meanwhile, are a rather uncanny model for the zebrafish’s ecosystems in the wild: with carefully regulated water temperatures and oxygen levels; breeding grounds simulated in sloped plastic dishes; and an environment sanitised of pathogens and predators. Ultimately, it is a highly controlled, artificial world with very little in common with the zebrafish’s wild habitats.

Simultaneously, researchers are attempting to construct computational models of the fish — a model of the model – so that perhaps one day live fish are no longer needed for scientific research. These are some of the multiple layers of abstraction I have come across, each one a step further removed from the original.

And yet even the laboratory fish are no longer quite “original”. Bred for generations in controlled environments, their genomes have diverged from wild populations. The pervasiveness of transgenic lines – fish engineered for particular research purposes – only amplifies this genetic divide. So even as a model to understand its own species in the wild, lab zebrafish are not particularly representative.

Accuracy to ‘the real thing,’ I have come to realise, is not exactly the aim. What is required from models in scientific research is a stable, controllable set of variables – an environment that can be regulated and reproduced. The abstract model is therefore, quite intentionally, untethered from messy ecological realities, and becomes the primary object of study.

What I am hoping to draw out with my project is the visceral weirdness of some of these relationships and layered substitutions – and bring the unruly messiness of ecological entanglements back into focus.

JF - Your fieldwork moves from petri dishes to rivers in northern India, from domestic aquariums to industrial infrastructures. How have these sites altered your perception of scale and intimacy, and where have you felt the boundary between species becoming most porous?

CK - The porosity between species felt most tangible to me when looking at all of these different environments collectively – from a petri dish in the lab, to pet shops, to server farms, to rivers and rice paddies in northern India. One of the main outcomes of the project is a short film which brings together these many contexts where human and zebrafish worlds collide, showcasing the complex ways in which these two species, our bodies and ecosystems are deeply entangled at planetary scale.

Zebrafish are altering our bodies in indirect but significant ways, given their role in biomedical research. Human clinical trials for treatments that repair retinal tissue are currently under way, for example, thanks to what has been learned from fish. Simultaneously, humans are drastically reconfiguring the life worlds of this small fish – with more zebrafish living in laboratories across the world than in the wild. They are one of the most popular species in the global aquarium trade, living as companions in domestic spaces, and all the while anthropogenic activity and climate change are disrupting their remaining ecosystems in the wild.

As part of my research, I spoke with one of the few ecologists who study zebrafish in the wild across the Indian subcontinent. He described the cultural significance of these small fish, and how Indian farmers have lived alongside them for thousands of years – welcoming them into their flooded rice paddies, as they help to maintain an ecological balance by eating insects and regulating carbon flux. This is the most reciprocal relationship I encountered as part of my fieldwork. Most other contexts, although porous in their boundaries between the two species, are dominated by our anthropocentric desires.

I suppose my hope is that, by confronting these deep connections – spanning millions of years, from our shared evolutionary history to the present – and by foregrounding a kind of intimacy between species that stretches from microscopic to planetary scales, the film might, in some small way, contribute to the emergence of a different cultural view of the zebrafish — one which acknowledges its significance, and where this porosity between species perhaps can become more reciprocal.

JF - Speculating 100 years ahead, the project imagines regenerative human hearts and human tissues grown from fish cells. Do you see these futures as acts of care or extraction?

CK - Current scientific research is actively studying the regenerative abilities of zebrafish, in the hopes of learning from the fish and bringing this into the human body. This type of research could give rise to biomedical treatments which allow us to repair our hearts, retinas, spinal cords, and other organs.

The idea of human tissue grown from fish cells, too, is described on the website of an existing research group. Apparently if the physical laws at play in tissue formation are understood, then they can also be manipulated – meaning that it would be hypothetically possible to grow fish cells into the shape of human tissue. So these are not distant speculations, but rather research that is already happening in the here and now!

Currently these efforts are largely extractive – driven by a desire to heal our bodies, learn about our biology, and advance human knowledge. Zebrafish are not benefiting from this.

Looking to the future, these research efforts point to a world where the boundaries between the bodies of humans and fish will only continue to blur. For me, this trajectory is an opportunity to insert myself as an artist, to consider potential interspecies futures that move beyond extraction.

I’m interested in building literacy around how labs, ecologies, and culture intersect, and raising important philosophical and ethical questions on the potential planetary implications of molecular scale research – bringing into dialogue our often extractive relationships to non-human worlds, and possibilities to unsettle them. How might zebrafish alter perceptions of our own bodies, for example? Do entrenched ideas of human exceptionalism, of us as somehow separate from and superior to other life forms, become harder to uphold in a world where we’re learning from fish, using them as models for our own body, and searching for foundational principles connecting all life?

What kinds of cultural shifts might this produce, and how might this contribute to a necessary recalibration in relationships between human and non-human worlds in the context of the climate crisis? Could potential positive transformations emerge from an interspecies approach to research & technology, and what might this look like? These are the types of questions and speculations I have been thinking about with the project.

JF - Much of your practice pushes the boundaries of human perception, exploring molecular processes, deep time and non-human sensing. Where do you see imagination becoming a necessary tool for ecological responsibility?