BY DIRK VIS

The White Light of the Beginning

White light pushes away a swirling cacophony of brightly coloured forms; there is no more clamour, distraction, or seduction, just peace. You’re in a crystal chamber; a space without objects, expanding into infinity; in the flaming white pearl of the great maker; the foamy spring of vital energy; in all-encompassing, unconditional love; supernatural light pervades your limbs; splendour shines not just around or above you, but throughout your heart and lungs. It’s the most intense experience possible; the mind containing all objects, situations, thoughts, and feelings, of everyone and everything, everywhere and of all times; a supernova exploding silently in the middle of your head. You’re inside a white hole, where time and space fuse; a singularity; a white-out. Here, loving others and acquiring knowledge are clearly all that matters, independently of dogma and ideology. Without worrying whether there will be life for you after death, you experience eternity, in gratitude.

You may have experienced the clear, white light of the beginning without having ever touched psychedelics. Or perhaps, you’ve been doing psychedelics for years, and still have never been anywhere near. Either way, many wisdom traditions recognise the experience of a white light. The white light is a clear marker of specific, psychedelic substances, but it also occurs through techniques, as the result of a long and dedicated discipline, or, sometimes, even spontaneously.

It is an otherworldly place, utterly weird. It feels and looks unearthly, but also: it feels like home. It may be the house of your unconscious – or your over-conscious, according to others – a home you forgot you had. And as you likely haven’t been there in a while, it might just need some care.

The creation of this light happens when you learn to shift attention from one field of consciousness to another. In physiological terms, this means: when you do everything you can to attend to your physical, mental and social wellbeing, and then you let go, allowing your nervous system to do the rest. This is your capacity to allow your everyday, active awareness to be witnessed by a second, observing, non-acting consciousness.

It can happen during meditation too: attention turns in on itself, while everything from the outer world flows away. You can cultivate it, one step deeper every time. In more ways than one, this move is similar to when you take a step back from creative work: you stop making, and witness what was made. You gain an overview. When you, later, go back to making and you continue – perhaps differently, perhaps just as you were – forgetting the overview, not knowing but trusting where to go. You hold space for the obscurity of something you allow yourself not to know. After the white light, the work becomes about embracing the dark.

Seemingly simple creative operations like this – unplanned, but continuously tweaked – can grow unpredictable results. For a mandala to generate something almost incalculable, unknowable, the process takes easy, simple steps. The resulting, complex form documents the process in which you have let go of trying to grasp complexity.

However you find or experience this switch between light and darkness, until you do, psychedelics might be entertainment, escapism, therapy, but not quite yet study. Yet, the clear light of the beginning is not an end goal, physiologically or metaphorically. That is to say that you cannot expect enlightenment, and even if that were available, it would not be about you, but rather a manifestation of the presence of everything around you, that you might have been too preoccupied or alienated to have noticed before.

Once you have given new life to this home of white light, you will know you can find your way back to it, in different ways. And when, and if, you do return, it will become a place ready for you to invite others into: new questions, presences and ways of being that are beginning to make themselves known to you.

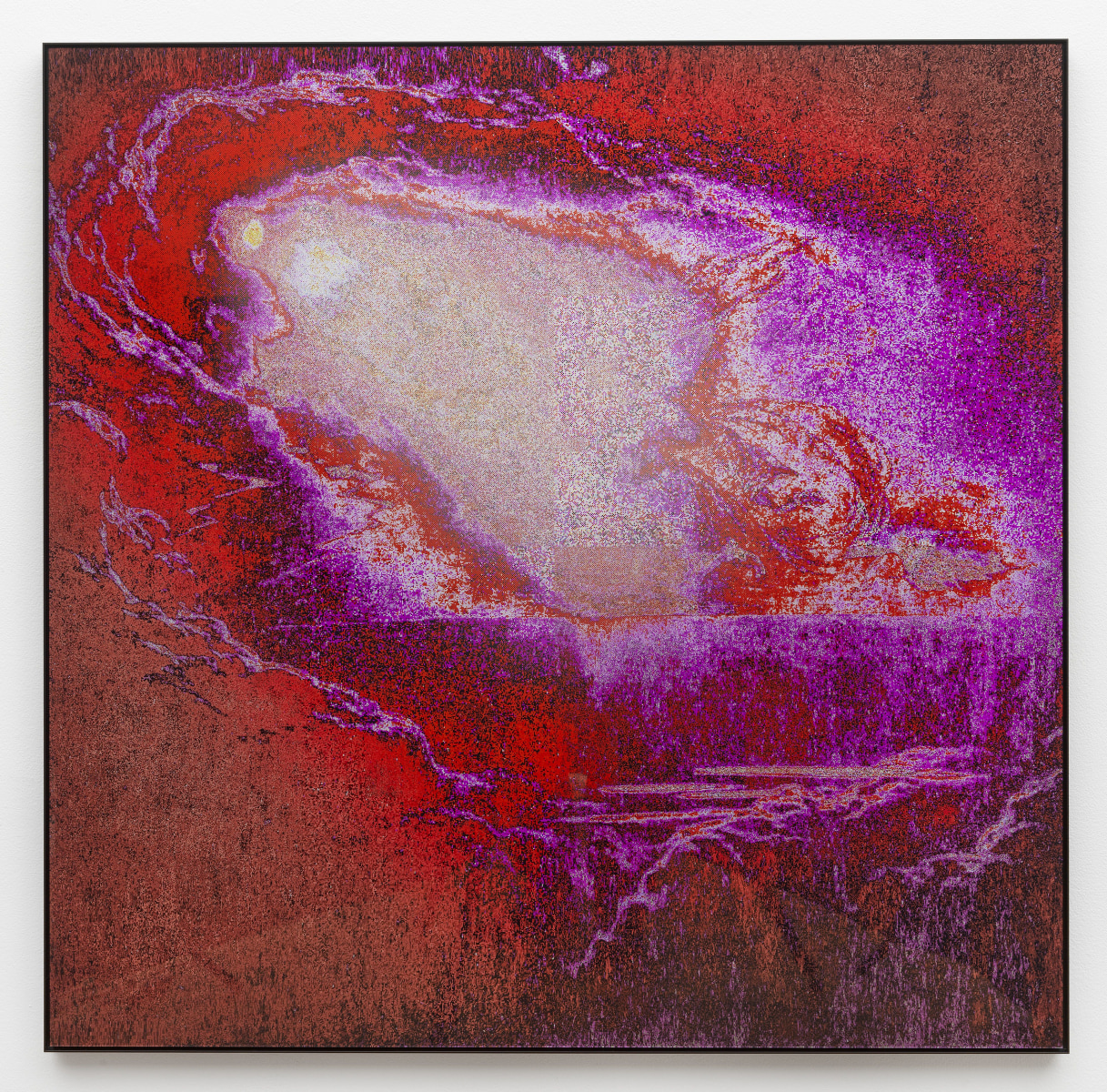

Image Credit:

Harm van den Dorpel, Creation of Light, 2024. Wall object. Photographic exposure on metallic paper. 100 × 100cm / 39.4 × 39.4″

Why Psychedelic Study?

Study isn’t often thought of as love. Effort and eagerness towards knowledge, yes, but knowledge is usually treated as something that can be undertaken, wrapped up, packaged, used, and commodified. Yet, there are other ways of understanding knowledge: to know something can mean to be able to attribute intentionality to it. Knowing your place in relation to what is studied is also knowledge. There are as many different forms of knowing, as there are forms of study.

The empirical, scientific and technological sciences study objects. But one’s subjective experience of the things that are being studied is equally necessary in order for the study itself to have any meaning. All study has a subjective element: it’s your vision, your drive, that will propel you to undertake the experiment in the first place. This visionary aspect of study is part of its subtly psychedelic side. Another way of saying this, is that there is an art to all study. Science looks for answers to solve problems that initially appear mysterious. Art celebrates mystery by problematising answers and expressing questions. One person can perform both of these roles, because ultimately, art and science are two sides of the same thing. Subjective study is expressed through art, where suddenly the psychedelic aspect of observation is not so subtle anymore, and becomes one of its main languages. Art is not a form of thinking per se: it is a form of being, yet it’s also a way of knowing. This is not the kind of knowledge that can be proven right or wrong. It is a kind of knowledge of the side of things that cannot be known. We can call this not-knowing. If the goal of objective study is to learn to understand, the goal of subjective study may be to learn to love.

Psychedelics, whether very subtly approached through dreaming, meditation or reflection, or whether actively induced through practicing techniques or taking substances, are portals to study. Psychedelic study is not mysticism, even if many experiences are difficult or appear impossible to describe. It is highly practical, and you can be very clear about what you do not know. It is the study of subjects, of experiences close to and far from your own, and it finds results in the shape of questions. Of course, just as empirical fieldwork can lead to visions, a psychedelic trip may bring clarity to an objective experiment or construction. But at the heart of psychedelic study are the immense mysteries that surround us. All you can do with those is learn to articulate the ways in which to ask about them.

A jungle of faces appears, each one metallic, geometric, yet weirdly plant-like. Each face pixelates, turns into a screen, showing yet newer vegetal faces. Messages flash between cells and selves. A tree emits more light than electronics ever could. Instead of the web, can you connect to a plant? Can you rediscover how life must have been for early hominids living in an untamed forest? Was there ever a home, in an unfarmed and fruitful land, where trees, waters and rocks were as alive as you and me?

Inner study: you are already doing it, you’ve always done it, every night, as you dream deeply. You’ve been doing it during daydreaming, too, during rest, therapy, hikes, holidays, festivals. Anytime you were able to make space for any of those unanswerable questions. It’s one of the oldest stories: you go into a cave, a desert or a forest – literal or metaphorical – long enough to realise it’s all an illusion, and when you come back out, you share what you have seen. Everything vibrates, nothing stands still. You already swim in a sea of light. A star breathes out, a black hole inhales. There is no time and no space. We simply keep changing, throughout spacetime: aeons ago merge with faraway futures into an ever-present now.

Image Credit:

Matrix Vegetal (still), Patricia Domínguez, 2021/22, commissioned by Screen City Biennial with the Support of Cecilia Brunson Projects.

The White Light of the Beginning

White light pushes away a swirling cacophony of brightly coloured forms; there is no more clamour, distraction, or seduction, just peace. You’re in a crystal chamber; a space without objects, expanding into infinity; in the flaming white pearl of the great maker; the foamy spring of vital energy; in all-encompassing, unconditional love; supernatural light pervades your limbs; splendour shines not just around or above you, but throughout your heart and lungs. It’s the most intense experience possible; the mind containing all objects, situations, thoughts, and feelings, of everyone and everything, everywhere and of all times; a supernova exploding silently in the middle of your head. You’re inside a white hole, where time and space fuse; a singularity; a white-out. Here, loving others and acquiring knowledge are clearly all that matters, independently of dogma and ideology. Without worrying whether there will be life for you after death, you experience eternity, in gratitude.

You may have experienced the clear, white light of the beginning without having ever touched psychedelics. Or perhaps, you’ve been doing psychedelics for years, and still have never been anywhere near. Either way, many wisdom traditions recognise the experience of a white light. The white light is a clear marker of specific, psychedelic substances, but it also occurs through techniques, as the result of a long and dedicated discipline, or, sometimes, even spontaneously.

It is an otherworldly place, utterly weird. It feels and looks unearthly, but also: it feels like home. It may be the house of your unconscious – or your over-conscious, according to others – a home you forgot you had. And as you likely haven’t been there in a while, it might just need some care.

The creation of this light happens when you learn to shift attention from one field of consciousness to another. In physiological terms, this means: when you do everything you can to attend to your physical, mental and social wellbeing, and then you let go, allowing your nervous system to do the rest. This is your capacity to allow your everyday, active awareness to be witnessed by a second, observing, non-acting consciousness.

It can happen during meditation too: attention turns in on itself, while everything from the outer world flows away. You can cultivate it, one step deeper every time. In more ways than one, this move is similar to when you take a step back from creative work: you stop making, and witness what was made. You gain an overview. When you, later, go back to making and you continue – perhaps differently, perhaps just as you were – forgetting the overview, not knowing but trusting where to go. You hold space for the obscurity of something you allow yourself not to know. After the white light, the work becomes about embracing the dark.

Seemingly simple creative operations like this – unplanned, but continuously tweaked – can grow unpredictable results. For a mandala to generate something almost incalculable, unknowable, the process takes easy, simple steps. The resulting, complex form documents the process in which you have let go of trying to grasp complexity.

However you find or experience this switch between light and darkness, until you do, psychedelics might be entertainment, escapism, therapy, but not quite yet study. Yet, the clear light of the beginning is not an end goal, physiologically or metaphorically. That is to say that you cannot expect enlightenment, and even if that were available, it would not be about you, but rather a manifestation of the presence of everything around you, that you might have been too preoccupied or alienated to have noticed before.

Once you have given new life to this home of white light, you will know you can find your way back to it, in different ways. And when, and if, you do return, it will become a place ready for you to invite others into: new questions, presences and ways of being that are beginning to make themselves known to you.

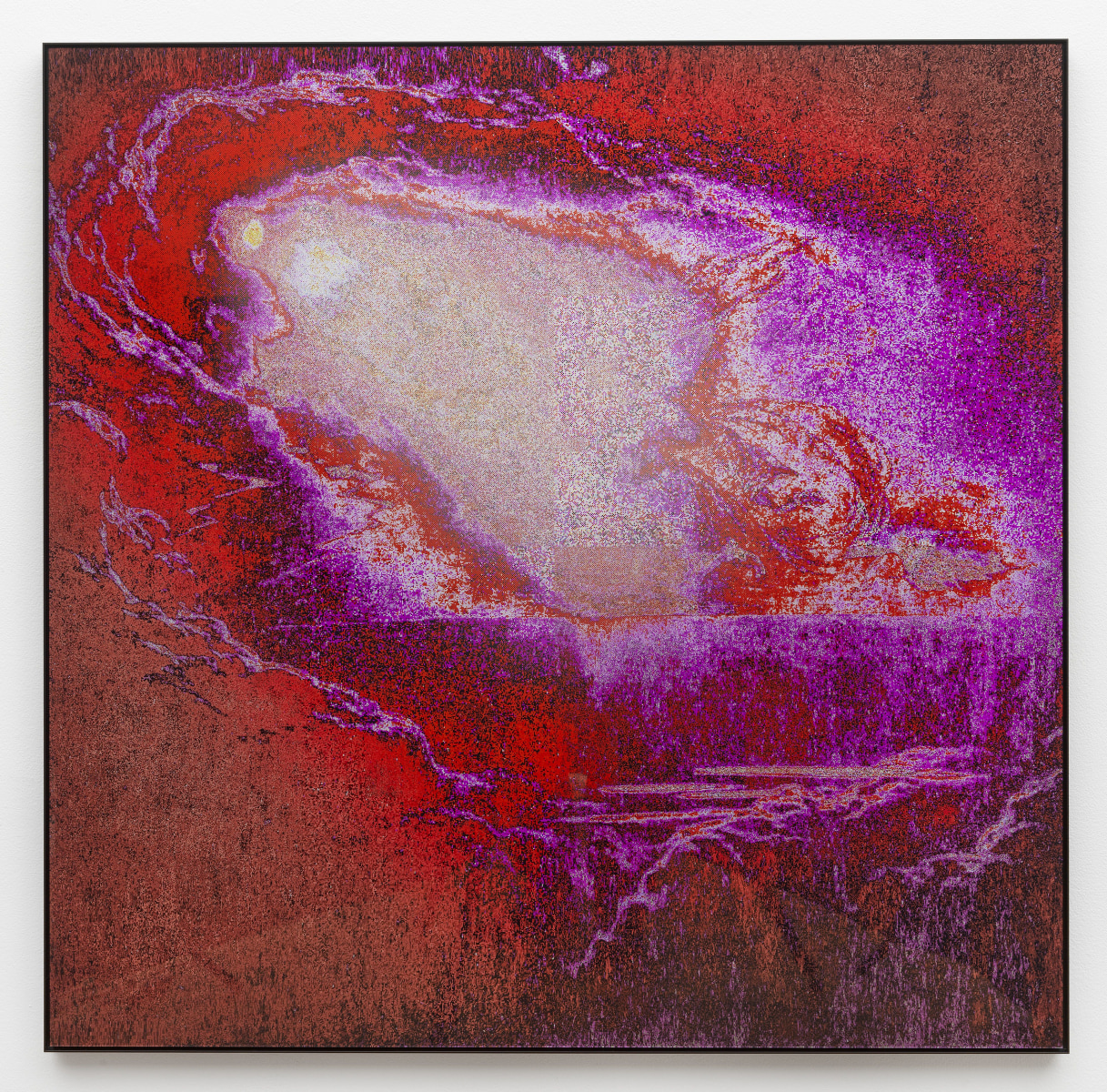

Image Credit:

Harm van den Dorpel, Creation of Light, 2024. Wall object. Photographic exposure on metallic paper. 100 × 100cm / 39.4 × 39.4″

Why Psychedelic Study?

Study isn’t often thought of as love. Effort and eagerness towards knowledge, yes, but knowledge is usually treated as something that can be undertaken, wrapped up, packaged, used, and commodified. Yet, there are other ways of understanding knowledge: to know something can mean to be able to attribute intentionality to it. Knowing your place in relation to what is studied is also knowledge. There are as many different forms of knowing, as there are forms of study.

The empirical, scientific and technological sciences study objects. But one’s subjective experience of the things that are being studied is equally necessary in order for the study itself to have any meaning. All study has a subjective element: it’s your vision, your drive, that will propel you to undertake the experiment in the first place. This visionary aspect of study is part of its subtly psychedelic side. Another way of saying this, is that there is an art to all study. Science looks for answers to solve problems that initially appear mysterious. Art celebrates mystery by problematising answers and expressing questions. One person can perform both of these roles, because ultimately, art and science are two sides of the same thing. Subjective study is expressed through art, where suddenly the psychedelic aspect of observation is not so subtle anymore, and becomes one of its main languages. Art is not a form of thinking per se: it is a form of being, yet it’s also a way of knowing. This is not the kind of knowledge that can be proven right or wrong. It is a kind of knowledge of the side of things that cannot be known. We can call this not-knowing. If the goal of objective study is to learn to understand, the goal of subjective study may be to learn to love.

Psychedelics, whether very subtly approached through dreaming, meditation or reflection, or whether actively induced through practicing techniques or taking substances, are portals to study. Psychedelic study is not mysticism, even if many experiences are difficult or appear impossible to describe. It is highly practical, and you can be very clear about what you do not know. It is the study of subjects, of experiences close to and far from your own, and it finds results in the shape of questions. Of course, just as empirical fieldwork can lead to visions, a psychedelic trip may bring clarity to an objective experiment or construction. But at the heart of psychedelic study are the immense mysteries that surround us. All you can do with those is learn to articulate the ways in which to ask about them.

A jungle of faces appears, each one metallic, geometric, yet weirdly plant-like. Each face pixelates, turns into a screen, showing yet newer vegetal faces. Messages flash between cells and selves. A tree emits more light than electronics ever could. Instead of the web, can you connect to a plant? Can you rediscover how life must have been for early hominids living in an untamed forest? Was there ever a home, in an unfarmed and fruitful land, where trees, waters and rocks were as alive as you and me?

Inner study: you are already doing it, you’ve always done it, every night, as you dream deeply. You’ve been doing it during daydreaming, too, during rest, therapy, hikes, holidays, festivals. Anytime you were able to make space for any of those unanswerable questions. It’s one of the oldest stories: you go into a cave, a desert or a forest – literal or metaphorical – long enough to realise it’s all an illusion, and when you come back out, you share what you have seen. Everything vibrates, nothing stands still. You already swim in a sea of light. A star breathes out, a black hole inhales. There is no time and no space. We simply keep changing, throughout spacetime: aeons ago merge with faraway futures into an ever-present now.

Image Credit:

Matrix Vegetal (still), Patricia Domínguez, 2021/22, commissioned by Screen City Biennial with the Support of Cecilia Brunson Projects.

Dirk Vis (1981) is a Dutch author of poetry, (science-)fiction, non-fiction and essays. Vis also published the ‘anti-manual’ Research For People Who (Think They) Would Rather Create. His book Study Trip is a forthcoming guide to psychedelics for research and art. A ‘study trip’ is a psychedelic journey embarked upon to learn about the world. The book offers a lucid guide through artistic, scientific, social, material and spiritual issues around psychedelics, with the goal of helping you find your own deeper questions.

Harm van den Dorpel’s practice focuses on emergent systems and the role technology plays in their development and meaning. Engaging with diverse materials and forms, including works on paper, sculpture, computer-generated graphics, and software, van den Dorpel’s works are continuously evolving, informed by feedback loops and the design of algorithmic systems. Working within and beyond the lineage of ‘net art’, a core aspect of van den Dorpel’s practice is software development that addresses specific approaches to artificial intelligence. With immense skill and craftsmanship, he builds advanced systems that draw on intuition and subliminal processes of the mind in order to continually output unexpected and curious aesthetic forms that embody a feeling of subconscious computation.

Patricia Domínguez is an artist based in Puchuncaví, Chile, and born in Santiago, Chile, in 1984. Assembling experimental research on ethnobotany, extractivism and healing practices, her work focuses on tracing spiritual relationships between living species in an increasingly digital and corporate cosmos. She proposes a poetic vision of contemporary life as deeply connected to the earth.She is the founder of Studio Vegetalista, an experimental platform for ethnobotanical research.

BY DIRK VIS

The White Light of the Beginning

White light pushes away a swirling cacophony of brightly coloured forms; there is no more clamour, distraction, or seduction, just peace. You’re in a crystal chamber; a space without objects, expanding into infinity; in the flaming white pearl of the great maker; the foamy spring of vital energy; in all-encompassing, unconditional love; supernatural light pervades your limbs; splendour shines not just around or above you, but throughout your heart and lungs. It’s the most intense experience possible; the mind containing all objects, situations, thoughts, and feelings, of everyone and everything, everywhere and of all times; a supernova exploding silently in the middle of your head. You’re inside a white hole, where time and space fuse; a singularity; a white-out. Here, loving others and acquiring knowledge are clearly all that matters, independently of dogma and ideology. Without worrying whether there will be life for you after death, you experience eternity, in gratitude.

You may have experienced the clear, white light of the beginning without having ever touched psychedelics. Or perhaps, you’ve been doing psychedelics for years, and still have never been anywhere near. Either way, many wisdom traditions recognise the experience of a white light. The white light is a clear marker of specific, psychedelic substances, but it also occurs through techniques, as the result of a long and dedicated discipline, or, sometimes, even spontaneously.

It is an otherworldly place, utterly weird. It feels and looks unearthly, but also: it feels like home. It may be the house of your unconscious – or your over-conscious, according to others – a home you forgot you had. And as you likely haven’t been there in a while, it might just need some care.

The creation of this light happens when you learn to shift attention from one field of consciousness to another. In physiological terms, this means: when you do everything you can to attend to your physical, mental and social wellbeing, and then you let go, allowing your nervous system to do the rest. This is your capacity to allow your everyday, active awareness to be witnessed by a second, observing, non-acting consciousness.

It can happen during meditation too: attention turns in on itself, while everything from the outer world flows away. You can cultivate it, one step deeper every time. In more ways than one, this move is similar to when you take a step back from creative work: you stop making, and witness what was made. You gain an overview. When you, later, go back to making and you continue – perhaps differently, perhaps just as you were – forgetting the overview, not knowing but trusting where to go. You hold space for the obscurity of something you allow yourself not to know. After the white light, the work becomes about embracing the dark.

Seemingly simple creative operations like this – unplanned, but continuously tweaked – can grow unpredictable results. For a mandala to generate something almost incalculable, unknowable, the process takes easy, simple steps. The resulting, complex form documents the process in which you have let go of trying to grasp complexity.

However you find or experience this switch between light and darkness, until you do, psychedelics might be entertainment, escapism, therapy, but not quite yet study. Yet, the clear light of the beginning is not an end goal, physiologically or metaphorically. That is to say that you cannot expect enlightenment, and even if that were available, it would not be about you, but rather a manifestation of the presence of everything around you, that you might have been too preoccupied or alienated to have noticed before.

Once you have given new life to this home of white light, you will know you can find your way back to it, in different ways. And when, and if, you do return, it will become a place ready for you to invite others into: new questions, presences and ways of being that are beginning to make themselves known to you.

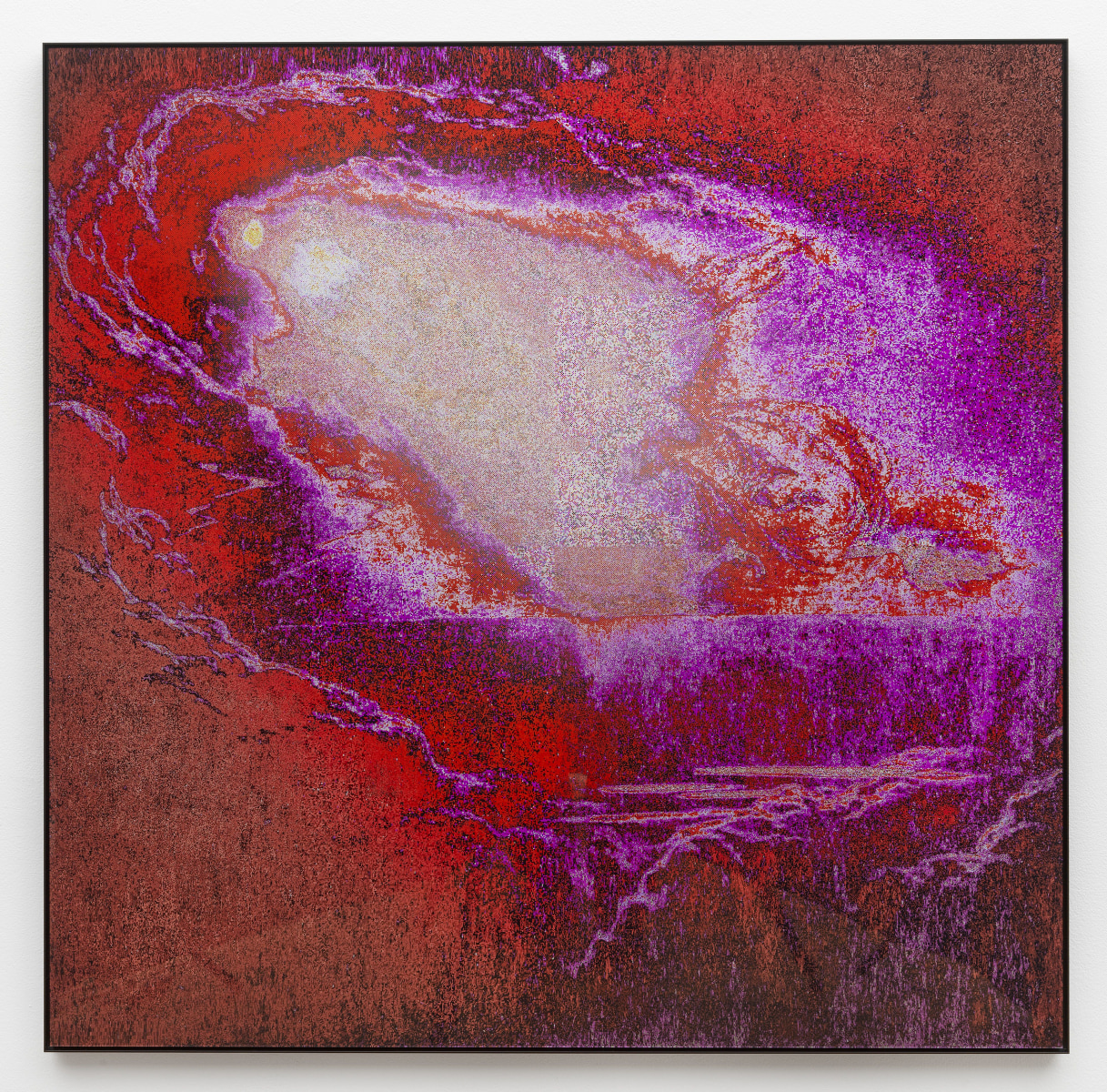

Image Credit:

Harm van den Dorpel, Creation of Light, 2024. Wall object. Photographic exposure on metallic paper. 100 × 100cm / 39.4 × 39.4″

Why Psychedelic Study?

Study isn’t often thought of as love. Effort and eagerness towards knowledge, yes, but knowledge is usually treated as something that can be undertaken, wrapped up, packaged, used, and commodified. Yet, there are other ways of understanding knowledge: to know something can mean to be able to attribute intentionality to it. Knowing your place in relation to what is studied is also knowledge. There are as many different forms of knowing, as there are forms of study.

The empirical, scientific and technological sciences study objects. But one’s subjective experience of the things that are being studied is equally necessary in order for the study itself to have any meaning. All study has a subjective element: it’s your vision, your drive, that will propel you to undertake the experiment in the first place. This visionary aspect of study is part of its subtly psychedelic side. Another way of saying this, is that there is an art to all study. Science looks for answers to solve problems that initially appear mysterious. Art celebrates mystery by problematising answers and expressing questions. One person can perform both of these roles, because ultimately, art and science are two sides of the same thing. Subjective study is expressed through art, where suddenly the psychedelic aspect of observation is not so subtle anymore, and becomes one of its main languages. Art is not a form of thinking per se: it is a form of being, yet it’s also a way of knowing. This is not the kind of knowledge that can be proven right or wrong. It is a kind of knowledge of the side of things that cannot be known. We can call this not-knowing. If the goal of objective study is to learn to understand, the goal of subjective study may be to learn to love.

Psychedelics, whether very subtly approached through dreaming, meditation or reflection, or whether actively induced through practicing techniques or taking substances, are portals to study. Psychedelic study is not mysticism, even if many experiences are difficult or appear impossible to describe. It is highly practical, and you can be very clear about what you do not know. It is the study of subjects, of experiences close to and far from your own, and it finds results in the shape of questions. Of course, just as empirical fieldwork can lead to visions, a psychedelic trip may bring clarity to an objective experiment or construction. But at the heart of psychedelic study are the immense mysteries that surround us. All you can do with those is learn to articulate the ways in which to ask about them.

A jungle of faces appears, each one metallic, geometric, yet weirdly plant-like. Each face pixelates, turns into a screen, showing yet newer vegetal faces. Messages flash between cells and selves. A tree emits more light than electronics ever could. Instead of the web, can you connect to a plant? Can you rediscover how life must have been for early hominids living in an untamed forest? Was there ever a home, in an unfarmed and fruitful land, where trees, waters and rocks were as alive as you and me?

Inner study: you are already doing it, you’ve always done it, every night, as you dream deeply. You’ve been doing it during daydreaming, too, during rest, therapy, hikes, holidays, festivals. Anytime you were able to make space for any of those unanswerable questions. It’s one of the oldest stories: you go into a cave, a desert or a forest – literal or metaphorical – long enough to realise it’s all an illusion, and when you come back out, you share what you have seen. Everything vibrates, nothing stands still. You already swim in a sea of light. A star breathes out, a black hole inhales. There is no time and no space. We simply keep changing, throughout spacetime: aeons ago merge with faraway futures into an ever-present now.

Image Credit:

Matrix Vegetal (still), Patricia Domínguez, 2021/22, commissioned by Screen City Biennial with the Support of Cecilia Brunson Projects.

The White Light of the Beginning

White light pushes away a swirling cacophony of brightly coloured forms; there is no more clamour, distraction, or seduction, just peace. You’re in a crystal chamber; a space without objects, expanding into infinity; in the flaming white pearl of the great maker; the foamy spring of vital energy; in all-encompassing, unconditional love; supernatural light pervades your limbs; splendour shines not just around or above you, but throughout your heart and lungs. It’s the most intense experience possible; the mind containing all objects, situations, thoughts, and feelings, of everyone and everything, everywhere and of all times; a supernova exploding silently in the middle of your head. You’re inside a white hole, where time and space fuse; a singularity; a white-out. Here, loving others and acquiring knowledge are clearly all that matters, independently of dogma and ideology. Without worrying whether there will be life for you after death, you experience eternity, in gratitude.

You may have experienced the clear, white light of the beginning without having ever touched psychedelics. Or perhaps, you’ve been doing psychedelics for years, and still have never been anywhere near. Either way, many wisdom traditions recognise the experience of a white light. The white light is a clear marker of specific, psychedelic substances, but it also occurs through techniques, as the result of a long and dedicated discipline, or, sometimes, even spontaneously.

It is an otherworldly place, utterly weird. It feels and looks unearthly, but also: it feels like home. It may be the house of your unconscious – or your over-conscious, according to others – a home you forgot you had. And as you likely haven’t been there in a while, it might just need some care.

The creation of this light happens when you learn to shift attention from one field of consciousness to another. In physiological terms, this means: when you do everything you can to attend to your physical, mental and social wellbeing, and then you let go, allowing your nervous system to do the rest. This is your capacity to allow your everyday, active awareness to be witnessed by a second, observing, non-acting consciousness.

It can happen during meditation too: attention turns in on itself, while everything from the outer world flows away. You can cultivate it, one step deeper every time. In more ways than one, this move is similar to when you take a step back from creative work: you stop making, and witness what was made. You gain an overview. When you, later, go back to making and you continue – perhaps differently, perhaps just as you were – forgetting the overview, not knowing but trusting where to go. You hold space for the obscurity of something you allow yourself not to know. After the white light, the work becomes about embracing the dark.

Seemingly simple creative operations like this – unplanned, but continuously tweaked – can grow unpredictable results. For a mandala to generate something almost incalculable, unknowable, the process takes easy, simple steps. The resulting, complex form documents the process in which you have let go of trying to grasp complexity.

However you find or experience this switch between light and darkness, until you do, psychedelics might be entertainment, escapism, therapy, but not quite yet study. Yet, the clear light of the beginning is not an end goal, physiologically or metaphorically. That is to say that you cannot expect enlightenment, and even if that were available, it would not be about you, but rather a manifestation of the presence of everything around you, that you might have been too preoccupied or alienated to have noticed before.

Once you have given new life to this home of white light, you will know you can find your way back to it, in different ways. And when, and if, you do return, it will become a place ready for you to invite others into: new questions, presences and ways of being that are beginning to make themselves known to you.

Image Credit:

Harm van den Dorpel, Creation of Light, 2024. Wall object. Photographic exposure on metallic paper. 100 × 100cm / 39.4 × 39.4″

Why Psychedelic Study?

Study isn’t often thought of as love. Effort and eagerness towards knowledge, yes, but knowledge is usually treated as something that can be undertaken, wrapped up, packaged, used, and commodified. Yet, there are other ways of understanding knowledge: to know something can mean to be able to attribute intentionality to it. Knowing your place in relation to what is studied is also knowledge. There are as many different forms of knowing, as there are forms of study.

The empirical, scientific and technological sciences study objects. But one’s subjective experience of the things that are being studied is equally necessary in order for the study itself to have any meaning. All study has a subjective element: it’s your vision, your drive, that will propel you to undertake the experiment in the first place. This visionary aspect of study is part of its subtly psychedelic side. Another way of saying this, is that there is an art to all study. Science looks for answers to solve problems that initially appear mysterious. Art celebrates mystery by problematising answers and expressing questions. One person can perform both of these roles, because ultimately, art and science are two sides of the same thing. Subjective study is expressed through art, where suddenly the psychedelic aspect of observation is not so subtle anymore, and becomes one of its main languages. Art is not a form of thinking per se: it is a form of being, yet it’s also a way of knowing. This is not the kind of knowledge that can be proven right or wrong. It is a kind of knowledge of the side of things that cannot be known. We can call this not-knowing. If the goal of objective study is to learn to understand, the goal of subjective study may be to learn to love.

Psychedelics, whether very subtly approached through dreaming, meditation or reflection, or whether actively induced through practicing techniques or taking substances, are portals to study. Psychedelic study is not mysticism, even if many experiences are difficult or appear impossible to describe. It is highly practical, and you can be very clear about what you do not know. It is the study of subjects, of experiences close to and far from your own, and it finds results in the shape of questions. Of course, just as empirical fieldwork can lead to visions, a psychedelic trip may bring clarity to an objective experiment or construction. But at the heart of psychedelic study are the immense mysteries that surround us. All you can do with those is learn to articulate the ways in which to ask about them.

A jungle of faces appears, each one metallic, geometric, yet weirdly plant-like. Each face pixelates, turns into a screen, showing yet newer vegetal faces. Messages flash between cells and selves. A tree emits more light than electronics ever could. Instead of the web, can you connect to a plant? Can you rediscover how life must have been for early hominids living in an untamed forest? Was there ever a home, in an unfarmed and fruitful land, where trees, waters and rocks were as alive as you and me?

Inner study: you are already doing it, you’ve always done it, every night, as you dream deeply. You’ve been doing it during daydreaming, too, during rest, therapy, hikes, holidays, festivals. Anytime you were able to make space for any of those unanswerable questions. It’s one of the oldest stories: you go into a cave, a desert or a forest – literal or metaphorical – long enough to realise it’s all an illusion, and when you come back out, you share what you have seen. Everything vibrates, nothing stands still. You already swim in a sea of light. A star breathes out, a black hole inhales. There is no time and no space. We simply keep changing, throughout spacetime: aeons ago merge with faraway futures into an ever-present now.

Image Credit:

Matrix Vegetal (still), Patricia Domínguez, 2021/22, commissioned by Screen City Biennial with the Support of Cecilia Brunson Projects.

Dirk Vis (1981) is a Dutch author of poetry, (science-)fiction, non-fiction and essays. Vis also published the ‘anti-manual’ Research For People Who (Think They) Would Rather Create. His book Study Trip is a forthcoming guide to psychedelics for research and art. A ‘study trip’ is a psychedelic journey embarked upon to learn about the world. The book offers a lucid guide through artistic, scientific, social, material and spiritual issues around psychedelics, with the goal of helping you find your own deeper questions.

Harm van den Dorpel’s practice focuses on emergent systems and the role technology plays in their development and meaning. Engaging with diverse materials and forms, including works on paper, sculpture, computer-generated graphics, and software, van den Dorpel’s works are continuously evolving, informed by feedback loops and the design of algorithmic systems. Working within and beyond the lineage of ‘net art’, a core aspect of van den Dorpel’s practice is software development that addresses specific approaches to artificial intelligence. With immense skill and craftsmanship, he builds advanced systems that draw on intuition and subliminal processes of the mind in order to continually output unexpected and curious aesthetic forms that embody a feeling of subconscious computation.

Patricia Domínguez is an artist based in Puchuncaví, Chile, and born in Santiago, Chile, in 1984. Assembling experimental research on ethnobotany, extractivism and healing practices, her work focuses on tracing spiritual relationships between living species in an increasingly digital and corporate cosmos. She proposes a poetic vision of contemporary life as deeply connected to the earth.She is the founder of Studio Vegetalista, an experimental platform for ethnobotanical research.

BY DIRK VIS

The White Light of the Beginning

White light pushes away a swirling cacophony of brightly coloured forms; there is no more clamour, distraction, or seduction, just peace. You’re in a crystal chamber; a space without objects, expanding into infinity; in the flaming white pearl of the great maker; the foamy spring of vital energy; in all-encompassing, unconditional love; supernatural light pervades your limbs; splendour shines not just around or above you, but throughout your heart and lungs. It’s the most intense experience possible; the mind containing all objects, situations, thoughts, and feelings, of everyone and everything, everywhere and of all times; a supernova exploding silently in the middle of your head. You’re inside a white hole, where time and space fuse; a singularity; a white-out. Here, loving others and acquiring knowledge are clearly all that matters, independently of dogma and ideology. Without worrying whether there will be life for you after death, you experience eternity, in gratitude.

You may have experienced the clear, white light of the beginning without having ever touched psychedelics. Or perhaps, you’ve been doing psychedelics for years, and still have never been anywhere near. Either way, many wisdom traditions recognise the experience of a white light. The white light is a clear marker of specific, psychedelic substances, but it also occurs through techniques, as the result of a long and dedicated discipline, or, sometimes, even spontaneously.

It is an otherworldly place, utterly weird. It feels and looks unearthly, but also: it feels like home. It may be the house of your unconscious – or your over-conscious, according to others – a home you forgot you had. And as you likely haven’t been there in a while, it might just need some care.

The creation of this light happens when you learn to shift attention from one field of consciousness to another. In physiological terms, this means: when you do everything you can to attend to your physical, mental and social wellbeing, and then you let go, allowing your nervous system to do the rest. This is your capacity to allow your everyday, active awareness to be witnessed by a second, observing, non-acting consciousness.

It can happen during meditation too: attention turns in on itself, while everything from the outer world flows away. You can cultivate it, one step deeper every time. In more ways than one, this move is similar to when you take a step back from creative work: you stop making, and witness what was made. You gain an overview. When you, later, go back to making and you continue – perhaps differently, perhaps just as you were – forgetting the overview, not knowing but trusting where to go. You hold space for the obscurity of something you allow yourself not to know. After the white light, the work becomes about embracing the dark.

Seemingly simple creative operations like this – unplanned, but continuously tweaked – can grow unpredictable results. For a mandala to generate something almost incalculable, unknowable, the process takes easy, simple steps. The resulting, complex form documents the process in which you have let go of trying to grasp complexity.

However you find or experience this switch between light and darkness, until you do, psychedelics might be entertainment, escapism, therapy, but not quite yet study. Yet, the clear light of the beginning is not an end goal, physiologically or metaphorically. That is to say that you cannot expect enlightenment, and even if that were available, it would not be about you, but rather a manifestation of the presence of everything around you, that you might have been too preoccupied or alienated to have noticed before.

Once you have given new life to this home of white light, you will know you can find your way back to it, in different ways. And when, and if, you do return, it will become a place ready for you to invite others into: new questions, presences and ways of being that are beginning to make themselves known to you.

Image Credit:

Harm van den Dorpel, Creation of Light, 2024. Wall object. Photographic exposure on metallic paper. 100 × 100cm / 39.4 × 39.4″

Why Psychedelic Study?

Study isn’t often thought of as love. Effort and eagerness towards knowledge, yes, but knowledge is usually treated as something that can be undertaken, wrapped up, packaged, used, and commodified. Yet, there are other ways of understanding knowledge: to know something can mean to be able to attribute intentionality to it. Knowing your place in relation to what is studied is also knowledge. There are as many different forms of knowing, as there are forms of study.

The empirical, scientific and technological sciences study objects. But one’s subjective experience of the things that are being studied is equally necessary in order for the study itself to have any meaning. All study has a subjective element: it’s your vision, your drive, that will propel you to undertake the experiment in the first place. This visionary aspect of study is part of its subtly psychedelic side. Another way of saying this, is that there is an art to all study. Science looks for answers to solve problems that initially appear mysterious. Art celebrates mystery by problematising answers and expressing questions. One person can perform both of these roles, because ultimately, art and science are two sides of the same thing. Subjective study is expressed through art, where suddenly the psychedelic aspect of observation is not so subtle anymore, and becomes one of its main languages. Art is not a form of thinking per se: it is a form of being, yet it’s also a way of knowing. This is not the kind of knowledge that can be proven right or wrong. It is a kind of knowledge of the side of things that cannot be known. We can call this not-knowing. If the goal of objective study is to learn to understand, the goal of subjective study may be to learn to love.

Psychedelics, whether very subtly approached through dreaming, meditation or reflection, or whether actively induced through practicing techniques or taking substances, are portals to study. Psychedelic study is not mysticism, even if many experiences are difficult or appear impossible to describe. It is highly practical, and you can be very clear about what you do not know. It is the study of subjects, of experiences close to and far from your own, and it finds results in the shape of questions. Of course, just as empirical fieldwork can lead to visions, a psychedelic trip may bring clarity to an objective experiment or construction. But at the heart of psychedelic study are the immense mysteries that surround us. All you can do with those is learn to articulate the ways in which to ask about them.

A jungle of faces appears, each one metallic, geometric, yet weirdly plant-like. Each face pixelates, turns into a screen, showing yet newer vegetal faces. Messages flash between cells and selves. A tree emits more light than electronics ever could. Instead of the web, can you connect to a plant? Can you rediscover how life must have been for early hominids living in an untamed forest? Was there ever a home, in an unfarmed and fruitful land, where trees, waters and rocks were as alive as you and me?

Inner study: you are already doing it, you’ve always done it, every night, as you dream deeply. You’ve been doing it during daydreaming, too, during rest, therapy, hikes, holidays, festivals. Anytime you were able to make space for any of those unanswerable questions. It’s one of the oldest stories: you go into a cave, a desert or a forest – literal or metaphorical – long enough to realise it’s all an illusion, and when you come back out, you share what you have seen. Everything vibrates, nothing stands still. You already swim in a sea of light. A star breathes out, a black hole inhales. There is no time and no space. We simply keep changing, throughout spacetime: aeons ago merge with faraway futures into an ever-present now.

Image Credit:

Matrix Vegetal (still), Patricia Domínguez, 2021/22, commissioned by Screen City Biennial with the Support of Cecilia Brunson Projects.

The White Light of the Beginning

White light pushes away a swirling cacophony of brightly coloured forms; there is no more clamour, distraction, or seduction, just peace. You’re in a crystal chamber; a space without objects, expanding into infinity; in the flaming white pearl of the great maker; the foamy spring of vital energy; in all-encompassing, unconditional love; supernatural light pervades your limbs; splendour shines not just around or above you, but throughout your heart and lungs. It’s the most intense experience possible; the mind containing all objects, situations, thoughts, and feelings, of everyone and everything, everywhere and of all times; a supernova exploding silently in the middle of your head. You’re inside a white hole, where time and space fuse; a singularity; a white-out. Here, loving others and acquiring knowledge are clearly all that matters, independently of dogma and ideology. Without worrying whether there will be life for you after death, you experience eternity, in gratitude.

You may have experienced the clear, white light of the beginning without having ever touched psychedelics. Or perhaps, you’ve been doing psychedelics for years, and still have never been anywhere near. Either way, many wisdom traditions recognise the experience of a white light. The white light is a clear marker of specific, psychedelic substances, but it also occurs through techniques, as the result of a long and dedicated discipline, or, sometimes, even spontaneously.

It is an otherworldly place, utterly weird. It feels and looks unearthly, but also: it feels like home. It may be the house of your unconscious – or your over-conscious, according to others – a home you forgot you had. And as you likely haven’t been there in a while, it might just need some care.

The creation of this light happens when you learn to shift attention from one field of consciousness to another. In physiological terms, this means: when you do everything you can to attend to your physical, mental and social wellbeing, and then you let go, allowing your nervous system to do the rest. This is your capacity to allow your everyday, active awareness to be witnessed by a second, observing, non-acting consciousness.

It can happen during meditation too: attention turns in on itself, while everything from the outer world flows away. You can cultivate it, one step deeper every time. In more ways than one, this move is similar to when you take a step back from creative work: you stop making, and witness what was made. You gain an overview. When you, later, go back to making and you continue – perhaps differently, perhaps just as you were – forgetting the overview, not knowing but trusting where to go. You hold space for the obscurity of something you allow yourself not to know. After the white light, the work becomes about embracing the dark.

Seemingly simple creative operations like this – unplanned, but continuously tweaked – can grow unpredictable results. For a mandala to generate something almost incalculable, unknowable, the process takes easy, simple steps. The resulting, complex form documents the process in which you have let go of trying to grasp complexity.

However you find or experience this switch between light and darkness, until you do, psychedelics might be entertainment, escapism, therapy, but not quite yet study. Yet, the clear light of the beginning is not an end goal, physiologically or metaphorically. That is to say that you cannot expect enlightenment, and even if that were available, it would not be about you, but rather a manifestation of the presence of everything around you, that you might have been too preoccupied or alienated to have noticed before.

Once you have given new life to this home of white light, you will know you can find your way back to it, in different ways. And when, and if, you do return, it will become a place ready for you to invite others into: new questions, presences and ways of being that are beginning to make themselves known to you.

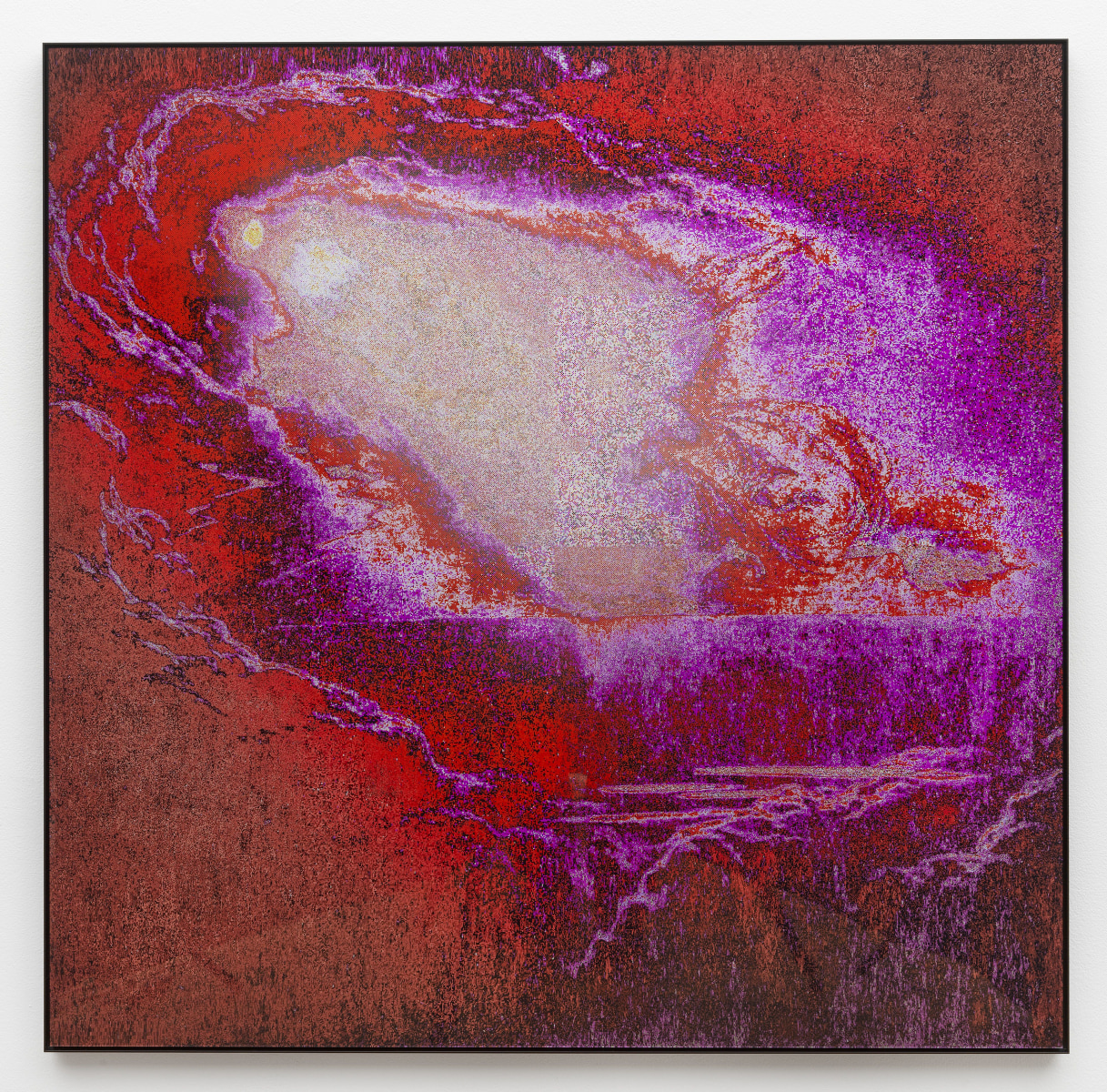

Image Credit:

Harm van den Dorpel, Creation of Light, 2024. Wall object. Photographic exposure on metallic paper. 100 × 100cm / 39.4 × 39.4″

Why Psychedelic Study?

Study isn’t often thought of as love. Effort and eagerness towards knowledge, yes, but knowledge is usually treated as something that can be undertaken, wrapped up, packaged, used, and commodified. Yet, there are other ways of understanding knowledge: to know something can mean to be able to attribute intentionality to it. Knowing your place in relation to what is studied is also knowledge. There are as many different forms of knowing, as there are forms of study.

The empirical, scientific and technological sciences study objects. But one’s subjective experience of the things that are being studied is equally necessary in order for the study itself to have any meaning. All study has a subjective element: it’s your vision, your drive, that will propel you to undertake the experiment in the first place. This visionary aspect of study is part of its subtly psychedelic side. Another way of saying this, is that there is an art to all study. Science looks for answers to solve problems that initially appear mysterious. Art celebrates mystery by problematising answers and expressing questions. One person can perform both of these roles, because ultimately, art and science are two sides of the same thing. Subjective study is expressed through art, where suddenly the psychedelic aspect of observation is not so subtle anymore, and becomes one of its main languages. Art is not a form of thinking per se: it is a form of being, yet it’s also a way of knowing. This is not the kind of knowledge that can be proven right or wrong. It is a kind of knowledge of the side of things that cannot be known. We can call this not-knowing. If the goal of objective study is to learn to understand, the goal of subjective study may be to learn to love.

Psychedelics, whether very subtly approached through dreaming, meditation or reflection, or whether actively induced through practicing techniques or taking substances, are portals to study. Psychedelic study is not mysticism, even if many experiences are difficult or appear impossible to describe. It is highly practical, and you can be very clear about what you do not know. It is the study of subjects, of experiences close to and far from your own, and it finds results in the shape of questions. Of course, just as empirical fieldwork can lead to visions, a psychedelic trip may bring clarity to an objective experiment or construction. But at the heart of psychedelic study are the immense mysteries that surround us. All you can do with those is learn to articulate the ways in which to ask about them.

A jungle of faces appears, each one metallic, geometric, yet weirdly plant-like. Each face pixelates, turns into a screen, showing yet newer vegetal faces. Messages flash between cells and selves. A tree emits more light than electronics ever could. Instead of the web, can you connect to a plant? Can you rediscover how life must have been for early hominids living in an untamed forest? Was there ever a home, in an unfarmed and fruitful land, where trees, waters and rocks were as alive as you and me?

Inner study: you are already doing it, you’ve always done it, every night, as you dream deeply. You’ve been doing it during daydreaming, too, during rest, therapy, hikes, holidays, festivals. Anytime you were able to make space for any of those unanswerable questions. It’s one of the oldest stories: you go into a cave, a desert or a forest – literal or metaphorical – long enough to realise it’s all an illusion, and when you come back out, you share what you have seen. Everything vibrates, nothing stands still. You already swim in a sea of light. A star breathes out, a black hole inhales. There is no time and no space. We simply keep changing, throughout spacetime: aeons ago merge with faraway futures into an ever-present now.

Image Credit:

Matrix Vegetal (still), Patricia Domínguez, 2021/22, commissioned by Screen City Biennial with the Support of Cecilia Brunson Projects.

Dirk Vis (1981) is a Dutch author of poetry, (science-)fiction, non-fiction and essays. Vis also published the ‘anti-manual’ Research For People Who (Think They) Would Rather Create. His book Study Trip is a forthcoming guide to psychedelics for research and art. A ‘study trip’ is a psychedelic journey embarked upon to learn about the world. The book offers a lucid guide through artistic, scientific, social, material and spiritual issues around psychedelics, with the goal of helping you find your own deeper questions.

Harm van den Dorpel’s practice focuses on emergent systems and the role technology plays in their development and meaning. Engaging with diverse materials and forms, including works on paper, sculpture, computer-generated graphics, and software, van den Dorpel’s works are continuously evolving, informed by feedback loops and the design of algorithmic systems. Working within and beyond the lineage of ‘net art’, a core aspect of van den Dorpel’s practice is software development that addresses specific approaches to artificial intelligence. With immense skill and craftsmanship, he builds advanced systems that draw on intuition and subliminal processes of the mind in order to continually output unexpected and curious aesthetic forms that embody a feeling of subconscious computation.

Patricia Domínguez is an artist based in Puchuncaví, Chile, and born in Santiago, Chile, in 1984. Assembling experimental research on ethnobotany, extractivism and healing practices, her work focuses on tracing spiritual relationships between living species in an increasingly digital and corporate cosmos. She proposes a poetic vision of contemporary life as deeply connected to the earth.She is the founder of Studio Vegetalista, an experimental platform for ethnobotanical research.

BY DIRK VIS

The White Light of the Beginning

White light pushes away a swirling cacophony of brightly coloured forms; there is no more clamour, distraction, or seduction, just peace. You’re in a crystal chamber; a space without objects, expanding into infinity; in the flaming white pearl of the great maker; the foamy spring of vital energy; in all-encompassing, unconditional love; supernatural light pervades your limbs; splendour shines not just around or above you, but throughout your heart and lungs. It’s the most intense experience possible; the mind containing all objects, situations, thoughts, and feelings, of everyone and everything, everywhere and of all times; a supernova exploding silently in the middle of your head. You’re inside a white hole, where time and space fuse; a singularity; a white-out. Here, loving others and acquiring knowledge are clearly all that matters, independently of dogma and ideology. Without worrying whether there will be life for you after death, you experience eternity, in gratitude.

You may have experienced the clear, white light of the beginning without having ever touched psychedelics. Or perhaps, you’ve been doing psychedelics for years, and still have never been anywhere near. Either way, many wisdom traditions recognise the experience of a white light. The white light is a clear marker of specific, psychedelic substances, but it also occurs through techniques, as the result of a long and dedicated discipline, or, sometimes, even spontaneously.

It is an otherworldly place, utterly weird. It feels and looks unearthly, but also: it feels like home. It may be the house of your unconscious – or your over-conscious, according to others – a home you forgot you had. And as you likely haven’t been there in a while, it might just need some care.

The creation of this light happens when you learn to shift attention from one field of consciousness to another. In physiological terms, this means: when you do everything you can to attend to your physical, mental and social wellbeing, and then you let go, allowing your nervous system to do the rest. This is your capacity to allow your everyday, active awareness to be witnessed by a second, observing, non-acting consciousness.

It can happen during meditation too: attention turns in on itself, while everything from the outer world flows away. You can cultivate it, one step deeper every time. In more ways than one, this move is similar to when you take a step back from creative work: you stop making, and witness what was made. You gain an overview. When you, later, go back to making and you continue – perhaps differently, perhaps just as you were – forgetting the overview, not knowing but trusting where to go. You hold space for the obscurity of something you allow yourself not to know. After the white light, the work becomes about embracing the dark.

Seemingly simple creative operations like this – unplanned, but continuously tweaked – can grow unpredictable results. For a mandala to generate something almost incalculable, unknowable, the process takes easy, simple steps. The resulting, complex form documents the process in which you have let go of trying to grasp complexity.

However you find or experience this switch between light and darkness, until you do, psychedelics might be entertainment, escapism, therapy, but not quite yet study. Yet, the clear light of the beginning is not an end goal, physiologically or metaphorically. That is to say that you cannot expect enlightenment, and even if that were available, it would not be about you, but rather a manifestation of the presence of everything around you, that you might have been too preoccupied or alienated to have noticed before.

Once you have given new life to this home of white light, you will know you can find your way back to it, in different ways. And when, and if, you do return, it will become a place ready for you to invite others into: new questions, presences and ways of being that are beginning to make themselves known to you.

Image Credit:

Harm van den Dorpel, Creation of Light, 2024. Wall object. Photographic exposure on metallic paper. 100 × 100cm / 39.4 × 39.4″

Why Psychedelic Study?

Study isn’t often thought of as love. Effort and eagerness towards knowledge, yes, but knowledge is usually treated as something that can be undertaken, wrapped up, packaged, used, and commodified. Yet, there are other ways of understanding knowledge: to know something can mean to be able to attribute intentionality to it. Knowing your place in relation to what is studied is also knowledge. There are as many different forms of knowing, as there are forms of study.

The empirical, scientific and technological sciences study objects. But one’s subjective experience of the things that are being studied is equally necessary in order for the study itself to have any meaning. All study has a subjective element: it’s your vision, your drive, that will propel you to undertake the experiment in the first place. This visionary aspect of study is part of its subtly psychedelic side. Another way of saying this, is that there is an art to all study. Science looks for answers to solve problems that initially appear mysterious. Art celebrates mystery by problematising answers and expressing questions. One person can perform both of these roles, because ultimately, art and science are two sides of the same thing. Subjective study is expressed through art, where suddenly the psychedelic aspect of observation is not so subtle anymore, and becomes one of its main languages. Art is not a form of thinking per se: it is a form of being, yet it’s also a way of knowing. This is not the kind of knowledge that can be proven right or wrong. It is a kind of knowledge of the side of things that cannot be known. We can call this not-knowing. If the goal of objective study is to learn to understand, the goal of subjective study may be to learn to love.

Psychedelics, whether very subtly approached through dreaming, meditation or reflection, or whether actively induced through practicing techniques or taking substances, are portals to study. Psychedelic study is not mysticism, even if many experiences are difficult or appear impossible to describe. It is highly practical, and you can be very clear about what you do not know. It is the study of subjects, of experiences close to and far from your own, and it finds results in the shape of questions. Of course, just as empirical fieldwork can lead to visions, a psychedelic trip may bring clarity to an objective experiment or construction. But at the heart of psychedelic study are the immense mysteries that surround us. All you can do with those is learn to articulate the ways in which to ask about them.

A jungle of faces appears, each one metallic, geometric, yet weirdly plant-like. Each face pixelates, turns into a screen, showing yet newer vegetal faces. Messages flash between cells and selves. A tree emits more light than electronics ever could. Instead of the web, can you connect to a plant? Can you rediscover how life must have been for early hominids living in an untamed forest? Was there ever a home, in an unfarmed and fruitful land, where trees, waters and rocks were as alive as you and me?

Inner study: you are already doing it, you’ve always done it, every night, as you dream deeply. You’ve been doing it during daydreaming, too, during rest, therapy, hikes, holidays, festivals. Anytime you were able to make space for any of those unanswerable questions. It’s one of the oldest stories: you go into a cave, a desert or a forest – literal or metaphorical – long enough to realise it’s all an illusion, and when you come back out, you share what you have seen. Everything vibrates, nothing stands still. You already swim in a sea of light. A star breathes out, a black hole inhales. There is no time and no space. We simply keep changing, throughout spacetime: aeons ago merge with faraway futures into an ever-present now.

Image Credit:

Matrix Vegetal (still), Patricia Domínguez, 2021/22, commissioned by Screen City Biennial with the Support of Cecilia Brunson Projects.

The White Light of the Beginning

White light pushes away a swirling cacophony of brightly coloured forms; there is no more clamour, distraction, or seduction, just peace. You’re in a crystal chamber; a space without objects, expanding into infinity; in the flaming white pearl of the great maker; the foamy spring of vital energy; in all-encompassing, unconditional love; supernatural light pervades your limbs; splendour shines not just around or above you, but throughout your heart and lungs. It’s the most intense experience possible; the mind containing all objects, situations, thoughts, and feelings, of everyone and everything, everywhere and of all times; a supernova exploding silently in the middle of your head. You’re inside a white hole, where time and space fuse; a singularity; a white-out. Here, loving others and acquiring knowledge are clearly all that matters, independently of dogma and ideology. Without worrying whether there will be life for you after death, you experience eternity, in gratitude.

You may have experienced the clear, white light of the beginning without having ever touched psychedelics. Or perhaps, you’ve been doing psychedelics for years, and still have never been anywhere near. Either way, many wisdom traditions recognise the experience of a white light. The white light is a clear marker of specific, psychedelic substances, but it also occurs through techniques, as the result of a long and dedicated discipline, or, sometimes, even spontaneously.

It is an otherworldly place, utterly weird. It feels and looks unearthly, but also: it feels like home. It may be the house of your unconscious – or your over-conscious, according to others – a home you forgot you had. And as you likely haven’t been there in a while, it might just need some care.

The creation of this light happens when you learn to shift attention from one field of consciousness to another. In physiological terms, this means: when you do everything you can to attend to your physical, mental and social wellbeing, and then you let go, allowing your nervous system to do the rest. This is your capacity to allow your everyday, active awareness to be witnessed by a second, observing, non-acting consciousness.

It can happen during meditation too: attention turns in on itself, while everything from the outer world flows away. You can cultivate it, one step deeper every time. In more ways than one, this move is similar to when you take a step back from creative work: you stop making, and witness what was made. You gain an overview. When you, later, go back to making and you continue – perhaps differently, perhaps just as you were – forgetting the overview, not knowing but trusting where to go. You hold space for the obscurity of something you allow yourself not to know. After the white light, the work becomes about embracing the dark.

Seemingly simple creative operations like this – unplanned, but continuously tweaked – can grow unpredictable results. For a mandala to generate something almost incalculable, unknowable, the process takes easy, simple steps. The resulting, complex form documents the process in which you have let go of trying to grasp complexity.

However you find or experience this switch between light and darkness, until you do, psychedelics might be entertainment, escapism, therapy, but not quite yet study. Yet, the clear light of the beginning is not an end goal, physiologically or metaphorically. That is to say that you cannot expect enlightenment, and even if that were available, it would not be about you, but rather a manifestation of the presence of everything around you, that you might have been too preoccupied or alienated to have noticed before.

Once you have given new life to this home of white light, you will know you can find your way back to it, in different ways. And when, and if, you do return, it will become a place ready for you to invite others into: new questions, presences and ways of being that are beginning to make themselves known to you.

Image Credit:

Harm van den Dorpel, Creation of Light, 2024. Wall object. Photographic exposure on metallic paper. 100 × 100cm / 39.4 × 39.4″

Why Psychedelic Study?

Study isn’t often thought of as love. Effort and eagerness towards knowledge, yes, but knowledge is usually treated as something that can be undertaken, wrapped up, packaged, used, and commodified. Yet, there are other ways of understanding knowledge: to know something can mean to be able to attribute intentionality to it. Knowing your place in relation to what is studied is also knowledge. There are as many different forms of knowing, as there are forms of study.

The empirical, scientific and technological sciences study objects. But one’s subjective experience of the things that are being studied is equally necessary in order for the study itself to have any meaning. All study has a subjective element: it’s your vision, your drive, that will propel you to undertake the experiment in the first place. This visionary aspect of study is part of its subtly psychedelic side. Another way of saying this, is that there is an art to all study. Science looks for answers to solve problems that initially appear mysterious. Art celebrates mystery by problematising answers and expressing questions. One person can perform both of these roles, because ultimately, art and science are two sides of the same thing. Subjective study is expressed through art, where suddenly the psychedelic aspect of observation is not so subtle anymore, and becomes one of its main languages. Art is not a form of thinking per se: it is a form of being, yet it’s also a way of knowing. This is not the kind of knowledge that can be proven right or wrong. It is a kind of knowledge of the side of things that cannot be known. We can call this not-knowing. If the goal of objective study is to learn to understand, the goal of subjective study may be to learn to love.

Psychedelics, whether very subtly approached through dreaming, meditation or reflection, or whether actively induced through practicing techniques or taking substances, are portals to study. Psychedelic study is not mysticism, even if many experiences are difficult or appear impossible to describe. It is highly practical, and you can be very clear about what you do not know. It is the study of subjects, of experiences close to and far from your own, and it finds results in the shape of questions. Of course, just as empirical fieldwork can lead to visions, a psychedelic trip may bring clarity to an objective experiment or construction. But at the heart of psychedelic study are the immense mysteries that surround us. All you can do with those is learn to articulate the ways in which to ask about them.

A jungle of faces appears, each one metallic, geometric, yet weirdly plant-like. Each face pixelates, turns into a screen, showing yet newer vegetal faces. Messages flash between cells and selves. A tree emits more light than electronics ever could. Instead of the web, can you connect to a plant? Can you rediscover how life must have been for early hominids living in an untamed forest? Was there ever a home, in an unfarmed and fruitful land, where trees, waters and rocks were as alive as you and me?

Inner study: you are already doing it, you’ve always done it, every night, as you dream deeply. You’ve been doing it during daydreaming, too, during rest, therapy, hikes, holidays, festivals. Anytime you were able to make space for any of those unanswerable questions. It’s one of the oldest stories: you go into a cave, a desert or a forest – literal or metaphorical – long enough to realise it’s all an illusion, and when you come back out, you share what you have seen. Everything vibrates, nothing stands still. You already swim in a sea of light. A star breathes out, a black hole inhales. There is no time and no space. We simply keep changing, throughout spacetime: aeons ago merge with faraway futures into an ever-present now.

Image Credit:

Matrix Vegetal (still), Patricia Domínguez, 2021/22, commissioned by Screen City Biennial with the Support of Cecilia Brunson Projects.

Dirk Vis (1981) is a Dutch author of poetry, (science-)fiction, non-fiction and essays. Vis also published the ‘anti-manual’ Research For People Who (Think They) Would Rather Create. His book Study Trip is a forthcoming guide to psychedelics for research and art. A ‘study trip’ is a psychedelic journey embarked upon to learn about the world. The book offers a lucid guide through artistic, scientific, social, material and spiritual issues around psychedelics, with the goal of helping you find your own deeper questions.

Harm van den Dorpel’s practice focuses on emergent systems and the role technology plays in their development and meaning. Engaging with diverse materials and forms, including works on paper, sculpture, computer-generated graphics, and software, van den Dorpel’s works are continuously evolving, informed by feedback loops and the design of algorithmic systems. Working within and beyond the lineage of ‘net art’, a core aspect of van den Dorpel’s practice is software development that addresses specific approaches to artificial intelligence. With immense skill and craftsmanship, he builds advanced systems that draw on intuition and subliminal processes of the mind in order to continually output unexpected and curious aesthetic forms that embody a feeling of subconscious computation.

Patricia Domínguez is an artist based in Puchuncaví, Chile, and born in Santiago, Chile, in 1984. Assembling experimental research on ethnobotany, extractivism and healing practices, her work focuses on tracing spiritual relationships between living species in an increasingly digital and corporate cosmos. She proposes a poetic vision of contemporary life as deeply connected to the earth.She is the founder of Studio Vegetalista, an experimental platform for ethnobotanical research.