BY FERNANDA GEBARA

Remembering Who We Are: From “Universe” to Pluriverse

I want to start this essay by remembering who we are, by remembering our own story.

If you trace your lineage back, generation by generation, you quickly reach a simple and unsettling realization: you are related to far more beings than your family tree can hold. Go back far enough and you are connected to every human who has ever lived and to every human alive today.

But the story doesn’t begin with humans.

To remember who we are, our lineage has to widen: to animals, birds, insects; to plants, trees, grasses, and waterborne vegetation; and further still, to the rocks, rivers, and mountains that form the Earth. Until our ancestry becomes universal.

The elements that make up our bodies and our world were forged in stars. The universe is not a distant “out there”; it is the long archive of our deepest lineage. We are stardust: animated by ancient forces that travelled through countless forms before arriving, briefly, as us.

So when we speak of the “universe” we are not speaking in abstractions. We are speaking of kinship. Of how the cosmos, matter, life, and intelligence (human and more-than-human, ancestral and artificial) are entangled in the same deep history.

When “Universe” Became a Scientific Language

By the 17th century, the “universe” became part of the language of modern science, especially after Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica (1687), which described a mechanistic universe functioning like a clock, ruled by universal laws of motion and gravity.

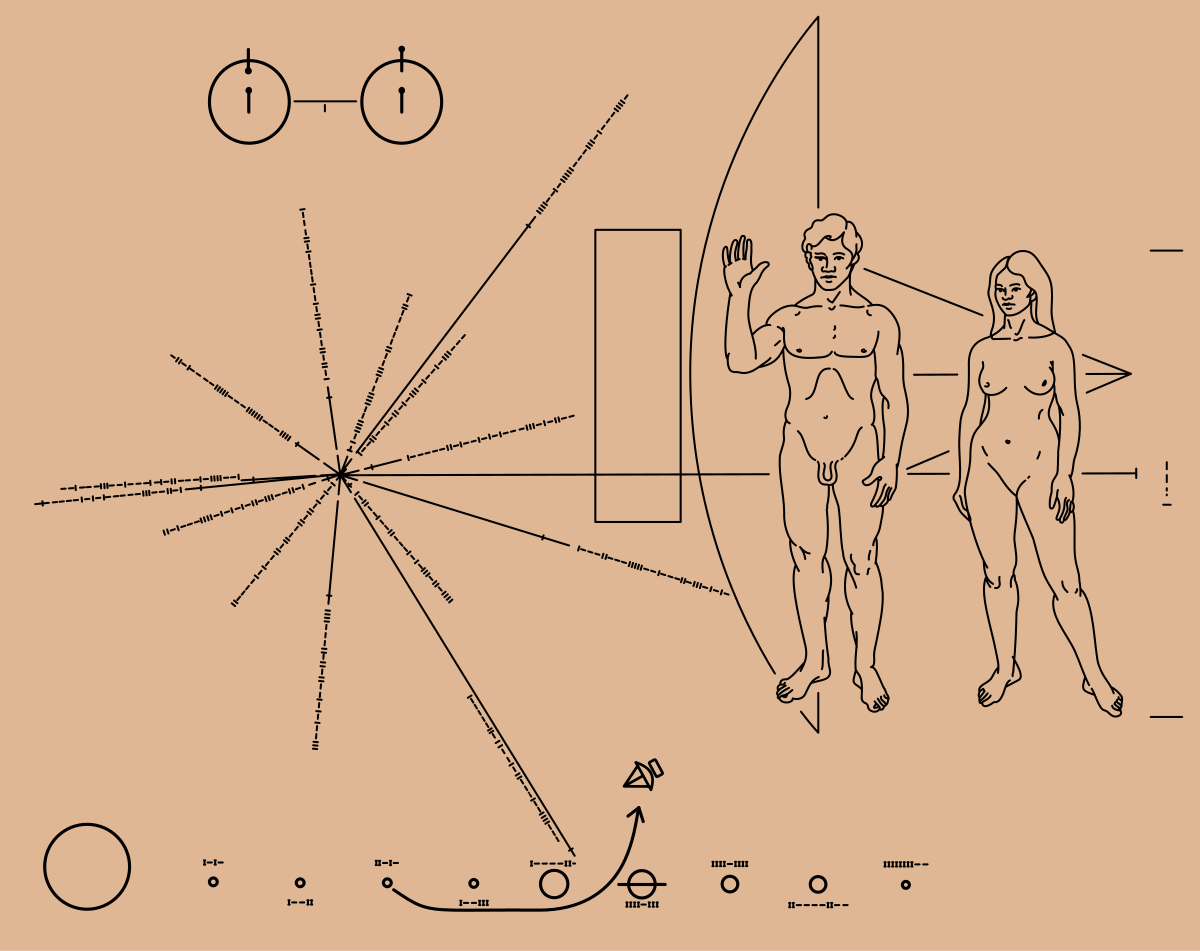

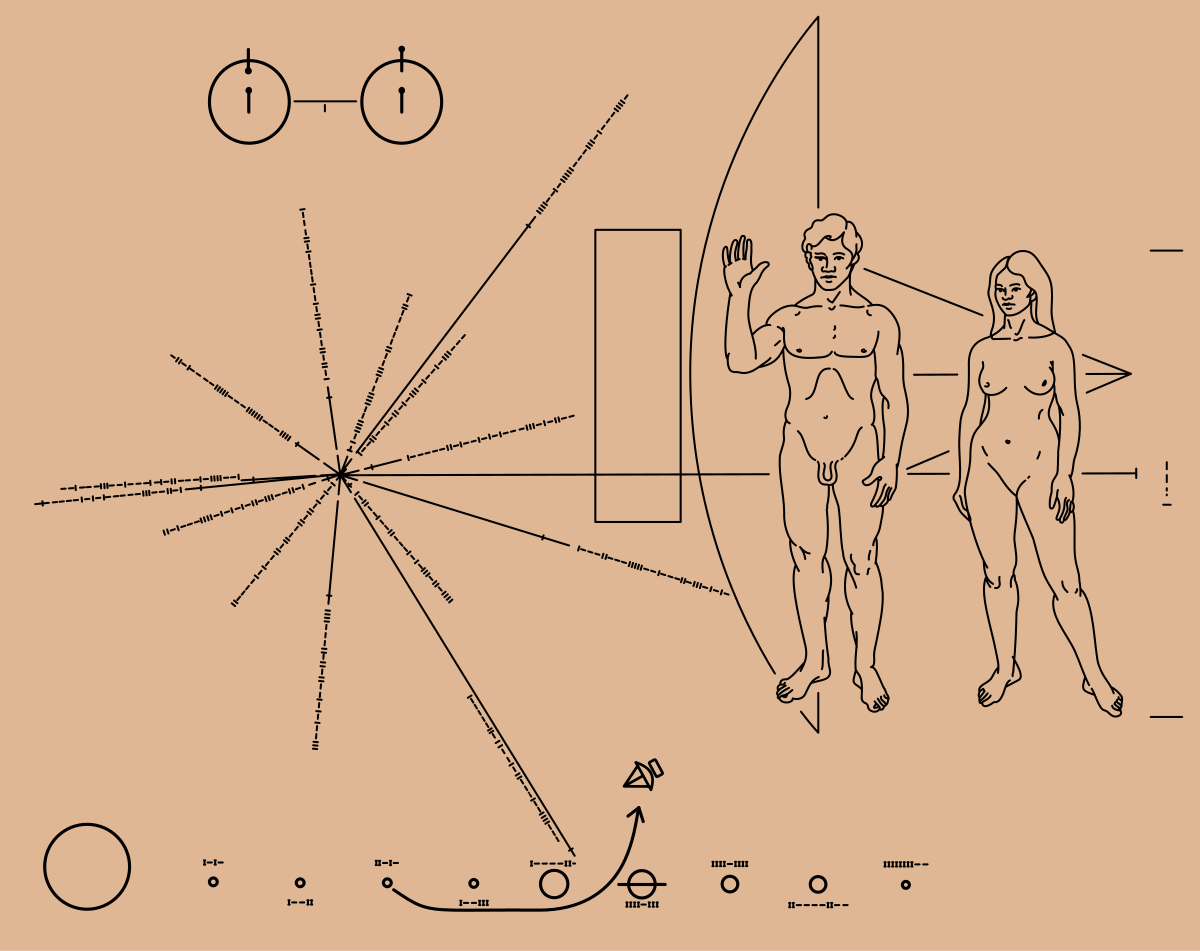

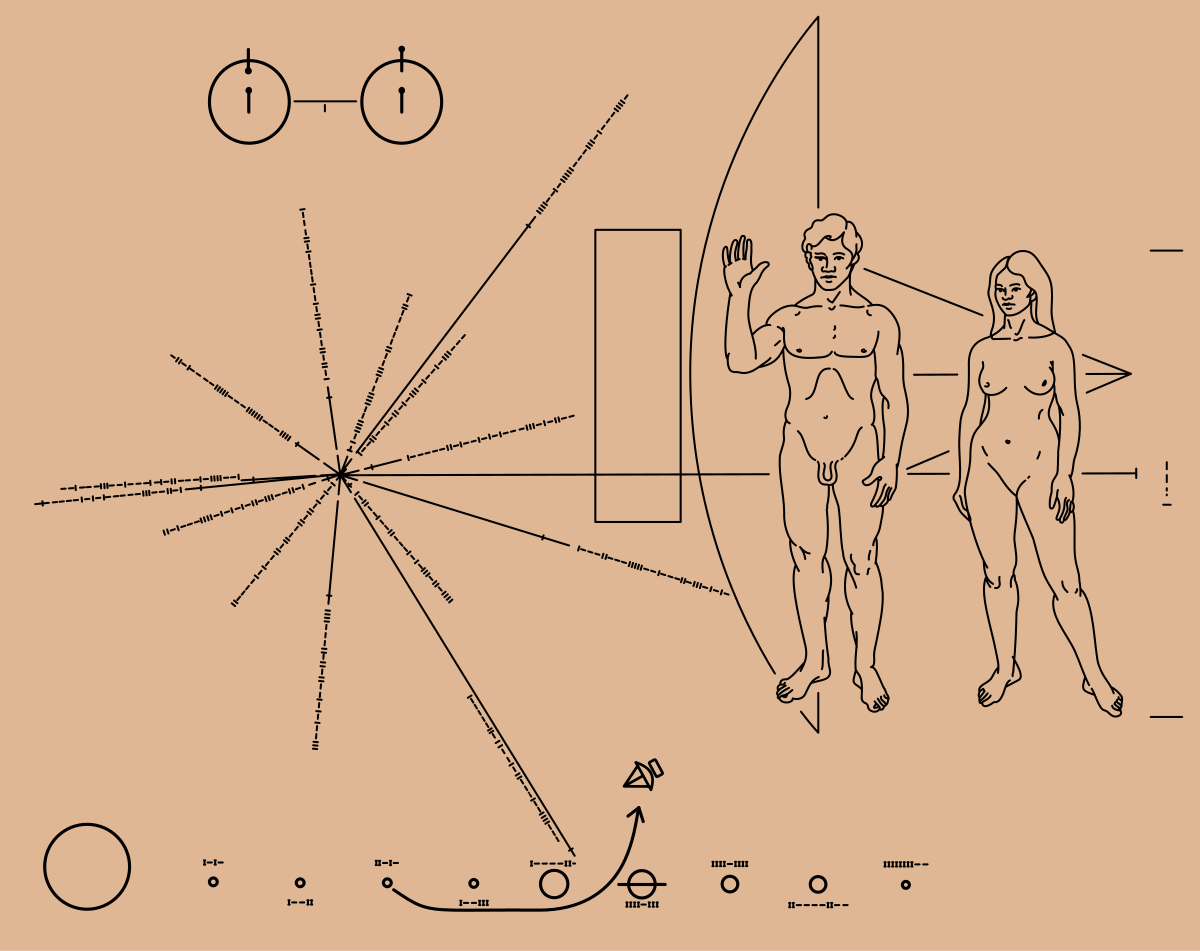

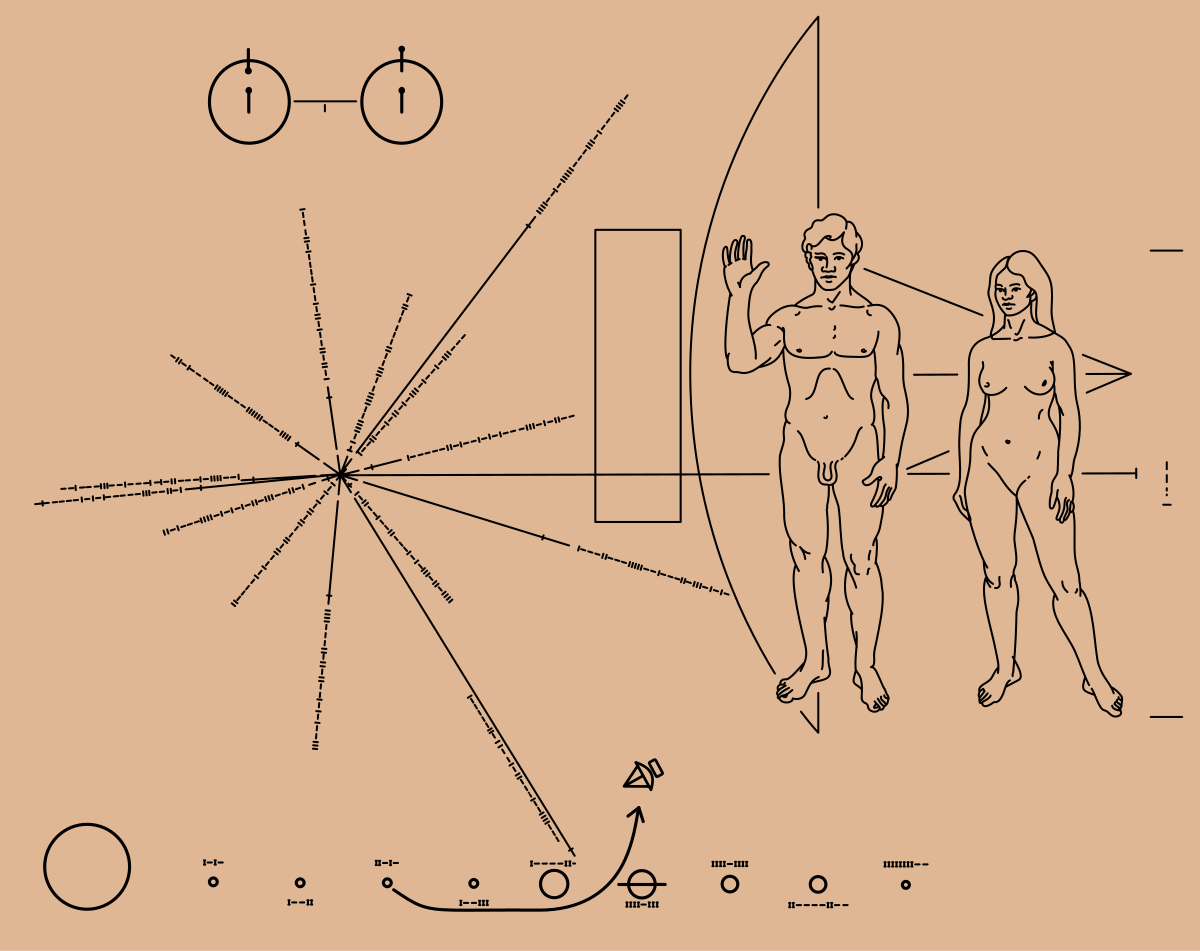

In the 1970s, humanity made its first deliberate attempts to communicate with other beings in the cosmos, possible extraterrestrial intelligences, through two NASA missions curated by Carl Sagan. Both carried messages from Earth designed in the language of science and mathematics, using symbols such as hydrogen atoms, binary numbers, and diagrams of our solar system.

These projects revealed something important: how deeply we relied on the epistemic framework of modern science (more specifically mathematics and physics) as if it were the only language capable of representing “the all,” the grammar through which reality is made intelligible.

Language as World-Making

As Jacques Lacan reminds us, language structures our reality: it is not merely a tool for communication, but the very framework through which we experience the world. He also compared language to mythology as a necessary construct of understanding.

And here I want to invite you to think about language in terms of the diverse ways we can speak with, and not just speak about.

Aníbal Quijano and Walter Mignolo argue that modernity’s so-called universal reason has always been entangled with coloniality. In this process, Europe’s scientific and philosophical frameworks were established as the only legitimate language of knowledge, imposing a single epistemic grammar and silencing other ontologies that were still dominant in the Americas before colonisation, especially Indigenous ones.

The belief that physics stands as the “mother” and ultimate model of all sciences - the one true Science—still endures. As James Watson once said: “What is not physics is mere social work.” In other words, knowledge that cannot be expressed through the mathematical language of physics is dismissed as unscientific.

So: what happens when one grammar or language claims the right to speak for reality itself? This is specially important in a moment where artificial intelligence (AI) is speaking for many.

The Pluriverse: Many grammars, many worlds

The discussion of many grammars, many languages, many worlds and “worldings” as ways of resisting dominant global world-making approaches could be traced back to William James. James coined the term pluriverse in 1907, proposing a reality made not of a single, unified world but of many worlds in the making.

Since then, pluriverse has travelled across different conversations, especially decolonial thought and cosmopolitics. In decolonial debates, the pluriverse is often described as a “world of worlds”: a direct challenge to the idea of the universe as one universal order, and an affirmation of world-making practices that exceed Western science.

Indigenous Cosmologies: The Sun Across Worlds

I want to share here some Indigenous beliefs, trying to link them to the pluriverse.

Ashaninka: Seeing Through Spirit

For the Ashaninka, Pawa—the Creator—brought into being the Sun (Oriya) and numerous invisible beings, referred to as spirits, who were entrusted with shaping the planets and the universe. Pawa gave the Sun a symbolic crown, marking him as co-creator. The Ashaninka headdress, resembling a crown, recalls this original gesture and embodies the people’s connection to the creative force of Pawa and the Sun.

The Sun is understood as a traveler, in perpetual movement, never resting, continually engaged in the work of creation alongside spiritual beings.

However, according to the Ashaninka, the eyes of contemporary humans can no longer perceive these beings. To see them, one must be spiritually connected, because perception occurs through the mind or spirit rather than through the physical senses. According to Moyses Ashaninka, human eyes can perceive only matter, and therefore cannot access the primordial time when the planet was conceived.

The Ashaninka conceive the world as composed of two principal realms: the material and the spiritual. Among them, the spiritual is considered the stronger, as it maintains the balance and continuity of the material world. Without care for the spiritual dimension, material life loses harmony and well-being.

Huni Kuin: Plants That Heal the Spirit

For the Huni Kuin, the Sun—called Bari—once lived in an enchanted and sacred state, resting very close to the Earth. It spoke with humans and with nature. And then at some point the Sun rose high into the sky.

The Sun gave them medicinal plants that carry the meaning of his name: Bari. These are plants for healing the spirit: for purification, bathing, eye medicine, inhalation, and cure.

Guarani: Words, Love, and Song to begin with

For the Guarani, the Sun is called Kuaray. Nhamandu, the creator, emerges from the primordial night, dwelling within the primordial wind. From Nhamandu’s wisdom, from his flame and his divine mist, are born the beautiful words (ayu rapyta). After that, he creates the source of infinite love (mborayu miri) and the divine song (mborai). And only then does he conceive his son: Kuaray, the Sun, destined to be the father of spirits (nhee).

So here we have the creation of words, love, and song before the Sun and all other spirits, showing that for the Guarani, words, love, and songs are primary languages of the cosmos.

The Enlightenment: Silencing of a Thousandfold World

The Sun plays a fundamental role in these cosmologies, as it plays also in Western science. They also recognize the dark, the long night, this cosmic being that “created” the Sun and the spirits.

But we all know that during the Enlightenment—which is literally related to the light, to illuminism—Descartes, Galileo, Newton, and others made rational thinking the rule, and with that devitalised the planet and all its living creatures, with the exception of the human.

The thousandfold languages of the natural world became inaudible to many humans.

In the past, everything (even for non-Indigenous people) had a “spirit,” an anima (the main idea behind animism). But when science silenced these different languages, our brains became adept at creating predictive models of reality and we gave up what neuroscientists and psychologists call “magical thinking.”

The modern ideal of knowledge is to describe and explain the world without recourse to the anima—spirit, intention, subject, emotion, consciousness, magic, whatever one chooses to call it.

The ideology of modern science is the complete de-spiritualisation or disenchantment of reality.

One day, perhaps, with all the advances in biogenetic research, we will even manage to do without the spirit in the case of humans themselves.

A Different Future: The Radical Spiritualisation of the World

I see Indigenous cosmologies and knowledge as betting precisely on the opposite: on the radical spiritualisation of the world.

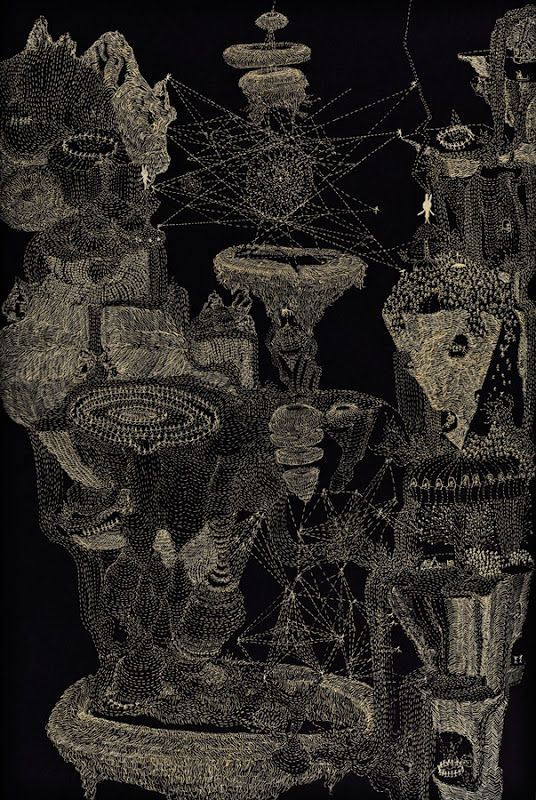

Every element of the world is endowed with intentionality and sociability, forming their own unique cultures, what Viveiros de Castro calls the multiplicity of cultures. In such a cosmology, every being comes into being through relations.

And this is reflected in the many languages used to communicate with other beings: painting, dancing, chanting, emitting sounds, dreaming. In some forms of art, it is almost like you can only truly speak with the other if you also become the other.

So how can we re-learn how to speak these different languages?

I think we probably need a spiritual turn, once for different Indigenous groups the spirit is the one that is able to speak these plural languages.

And I think this is already happening: many Westerners are increasingly engaging with Indigenous spiritual practices and other spiritual practices such as yoga, meditation, and so on. Of course there are many complex issues related to such a move that would require another essay to analyse, but still, it is happening.

Dreams, Darkness, and Nourishment

But let us go back to the dark, the original cosmic force.

Dreams, for example, are a great part of Indigenous spiritualities, and another way our spirit speaks. And I think we have not been able to dream anymore in our society. How can we dream if we are a society that does not sleep?

Indigenous writer Cristine Takuá (Maxacali) reminds us that nourishment is not only physical. Food feeds the body, but dreams feed the spirit. When we stop dreaming, the soul becomes anemic.

Carlos Papá, a spiritual leader of the Guarani people, teaches that healing and dreaming come from embracing darkness, the same darkness that once held us in the womb. When we close our eyes to pray or rest, we return to that sacred space where the spirit is nourished. Darkness, in that sense, is not absence but presence. When we return to that darkness, we awaken the outer darkness from which we all came: the cosmic darkness.

From Concepts to Practice: What Would It Take?

Many concepts and efforts circulate today: pluriverse, ontological turn, unlearning, rewilding, regenerating, decolonizing, multispecies justice, conviviality, degrowth, living well, relationality, the future is ancestral. But I wonder what we need to do to put them more into practice.

Maybe we need to rediscover the darkness, the same darkness that originated us, the cosmos, and the space within us. From that space, we could unlearn some of our practices and beliefs and remember who we are.

I do think we are walking in that direction somehow, with all the recognition science is giving to what Indigenous peoples have been talking about for millennia. Meanwhile, the more we want to debate, to prove, to question their ideas, we also lose time. Time that is so precious to make the changes we need to make so we can be fair with future generations.

Finally spirituality and science—despite what we’ve been taught—are not as different as they seem. Both seek to understand ourselves, society, nature, the universe, and even the pluriverse. We can think of them as complementary ways of inquiry, and it is time to bring spirituality and science into dialogue.

So I will leave you with one last reflection on remembering who we are. If we are stardust, if the rocks that shaped our planet carry the same minerals we now refine into the infrastructures of artificial intelligence, then AI is not only a cultural or technical artifact, but also a continuation of a much older, cosmological lineage. This makes me wonder: how much of AI’s language is truly “artificial,” and how much is the universe speaking back through new forms of matter and code? In that sense, AI is already a pluriverse in itself: a shifting assemblage of minerals, histories, human intentions, and more-than-human forces, co-producing worlds.

Image Credits:

1.Pioneer plague - NASA

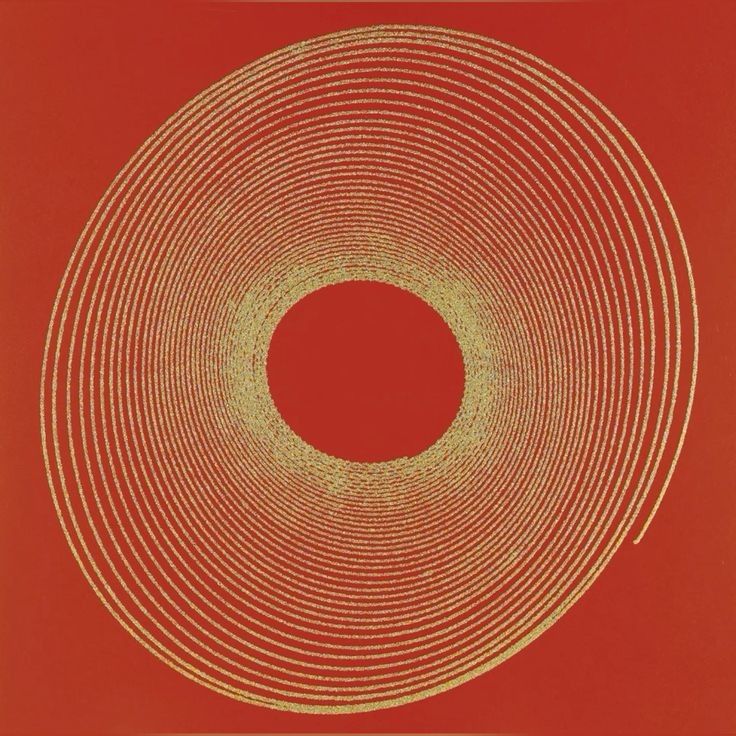

2.Golden Area by SSIN

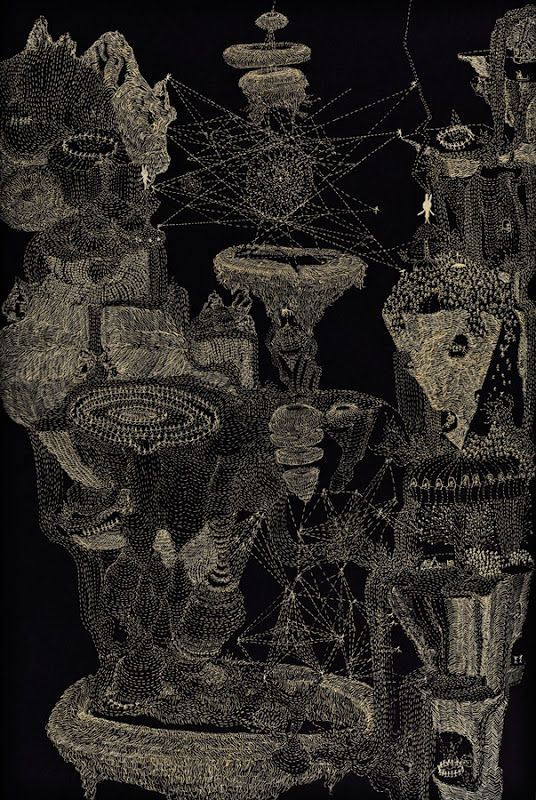

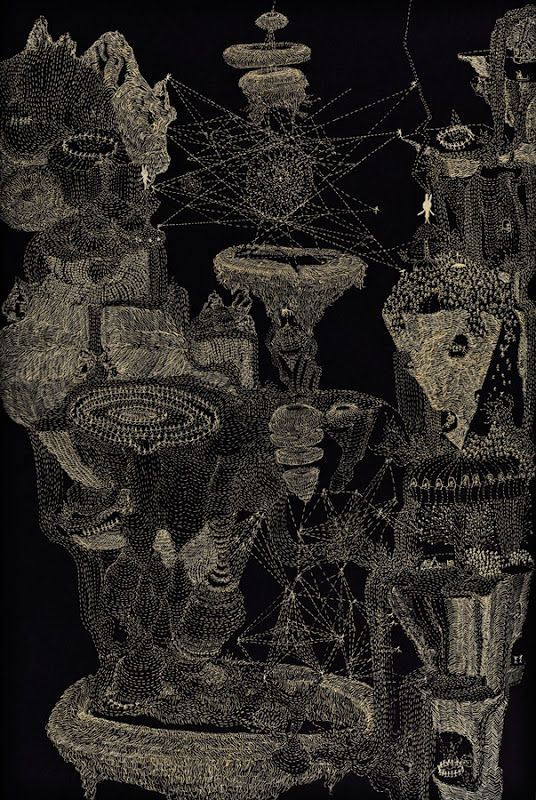

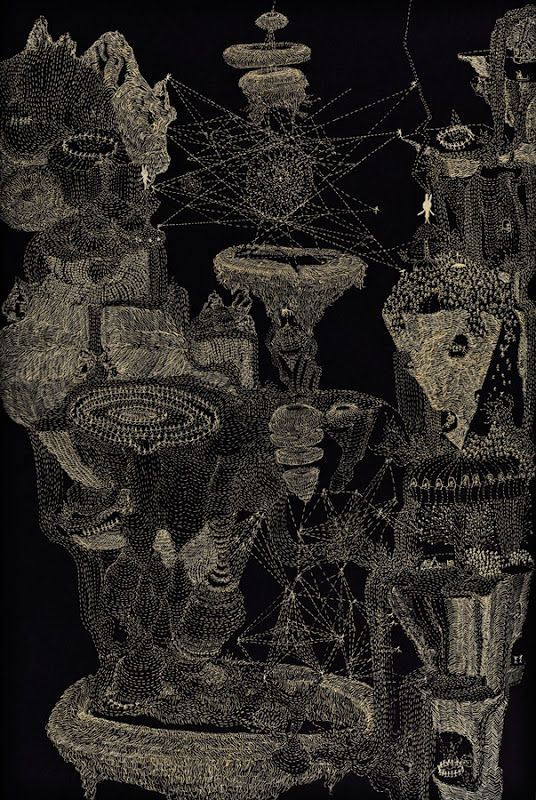

3.Hueco Guacamalla by Abel Rodriguez

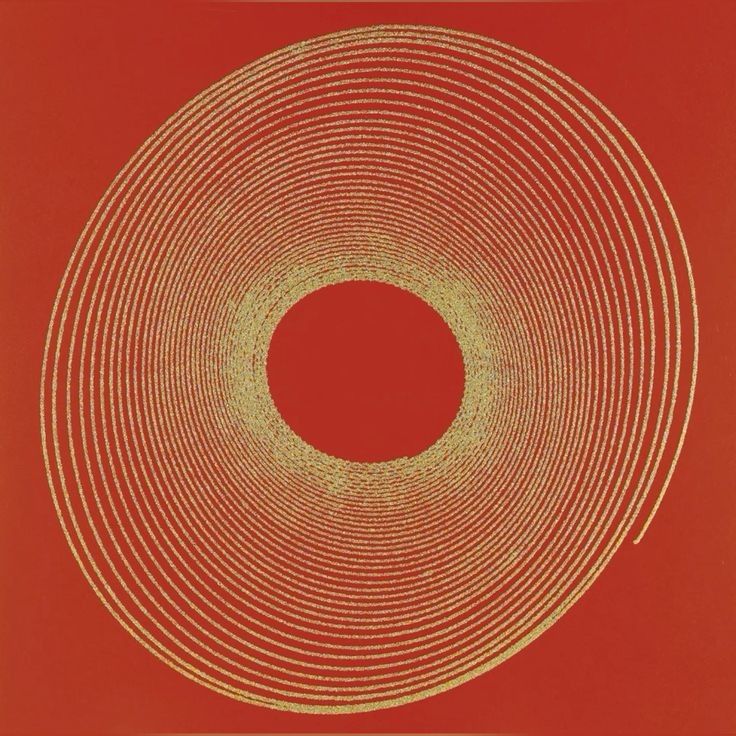

4.Spirale d'or by by Bassam Geitani

5.Yube Inu Yube Shanu by MAHKU (Huni Kuin Artists Movement)

76.Zirkus (Circus) by Unica Zürn, 1956

Remembering Who We Are: From “Universe” to Pluriverse

I want to start this essay by remembering who we are, by remembering our own story.

If you trace your lineage back, generation by generation, you quickly reach a simple and unsettling realization: you are related to far more beings than your family tree can hold. Go back far enough and you are connected to every human who has ever lived and to every human alive today.

But the story doesn’t begin with humans.

To remember who we are, our lineage has to widen: to animals, birds, insects; to plants, trees, grasses, and waterborne vegetation; and further still, to the rocks, rivers, and mountains that form the Earth. Until our ancestry becomes universal.

The elements that make up our bodies and our world were forged in stars. The universe is not a distant “out there”; it is the long archive of our deepest lineage. We are stardust: animated by ancient forces that travelled through countless forms before arriving, briefly, as us.

So when we speak of the “universe” we are not speaking in abstractions. We are speaking of kinship. Of how the cosmos, matter, life, and intelligence (human and more-than-human, ancestral and artificial) are entangled in the same deep history.

When “Universe” Became a Scientific Language

By the 17th century, the “universe” became part of the language of modern science, especially after Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica (1687), which described a mechanistic universe functioning like a clock, ruled by universal laws of motion and gravity.

In the 1970s, humanity made its first deliberate attempts to communicate with other beings in the cosmos, possible extraterrestrial intelligences, through two NASA missions curated by Carl Sagan. Both carried messages from Earth designed in the language of science and mathematics, using symbols such as hydrogen atoms, binary numbers, and diagrams of our solar system.

These projects revealed something important: how deeply we relied on the epistemic framework of modern science (more specifically mathematics and physics) as if it were the only language capable of representing “the all,” the grammar through which reality is made intelligible.

Language as World-Making

As Jacques Lacan reminds us, language structures our reality: it is not merely a tool for communication, but the very framework through which we experience the world. He also compared language to mythology as a necessary construct of understanding.

And here I want to invite you to think about language in terms of the diverse ways we can speak with, and not just speak about.

Aníbal Quijano and Walter Mignolo argue that modernity’s so-called universal reason has always been entangled with coloniality. In this process, Europe’s scientific and philosophical frameworks were established as the only legitimate language of knowledge, imposing a single epistemic grammar and silencing other ontologies that were still dominant in the Americas before colonisation, especially Indigenous ones.

The belief that physics stands as the “mother” and ultimate model of all sciences - the one true Science—still endures. As James Watson once said: “What is not physics is mere social work.” In other words, knowledge that cannot be expressed through the mathematical language of physics is dismissed as unscientific.

So: what happens when one grammar or language claims the right to speak for reality itself? This is specially important in a moment where artificial intelligence (AI) is speaking for many.

The Pluriverse: Many grammars, many worlds

The discussion of many grammars, many languages, many worlds and “worldings” as ways of resisting dominant global world-making approaches could be traced back to William James. James coined the term pluriverse in 1907, proposing a reality made not of a single, unified world but of many worlds in the making.

Since then, pluriverse has travelled across different conversations, especially decolonial thought and cosmopolitics. In decolonial debates, the pluriverse is often described as a “world of worlds”: a direct challenge to the idea of the universe as one universal order, and an affirmation of world-making practices that exceed Western science.

Indigenous Cosmologies: The Sun Across Worlds

I want to share here some Indigenous beliefs, trying to link them to the pluriverse.

Ashaninka: Seeing Through Spirit

For the Ashaninka, Pawa—the Creator—brought into being the Sun (Oriya) and numerous invisible beings, referred to as spirits, who were entrusted with shaping the planets and the universe. Pawa gave the Sun a symbolic crown, marking him as co-creator. The Ashaninka headdress, resembling a crown, recalls this original gesture and embodies the people’s connection to the creative force of Pawa and the Sun.

The Sun is understood as a traveler, in perpetual movement, never resting, continually engaged in the work of creation alongside spiritual beings.

However, according to the Ashaninka, the eyes of contemporary humans can no longer perceive these beings. To see them, one must be spiritually connected, because perception occurs through the mind or spirit rather than through the physical senses. According to Moyses Ashaninka, human eyes can perceive only matter, and therefore cannot access the primordial time when the planet was conceived.

The Ashaninka conceive the world as composed of two principal realms: the material and the spiritual. Among them, the spiritual is considered the stronger, as it maintains the balance and continuity of the material world. Without care for the spiritual dimension, material life loses harmony and well-being.

Huni Kuin: Plants That Heal the Spirit

For the Huni Kuin, the Sun—called Bari—once lived in an enchanted and sacred state, resting very close to the Earth. It spoke with humans and with nature. And then at some point the Sun rose high into the sky.

The Sun gave them medicinal plants that carry the meaning of his name: Bari. These are plants for healing the spirit: for purification, bathing, eye medicine, inhalation, and cure.

Guarani: Words, Love, and Song to begin with

For the Guarani, the Sun is called Kuaray. Nhamandu, the creator, emerges from the primordial night, dwelling within the primordial wind. From Nhamandu’s wisdom, from his flame and his divine mist, are born the beautiful words (ayu rapyta). After that, he creates the source of infinite love (mborayu miri) and the divine song (mborai). And only then does he conceive his son: Kuaray, the Sun, destined to be the father of spirits (nhee).

So here we have the creation of words, love, and song before the Sun and all other spirits, showing that for the Guarani, words, love, and songs are primary languages of the cosmos.

The Enlightenment: Silencing of a Thousandfold World

The Sun plays a fundamental role in these cosmologies, as it plays also in Western science. They also recognize the dark, the long night, this cosmic being that “created” the Sun and the spirits.

But we all know that during the Enlightenment—which is literally related to the light, to illuminism—Descartes, Galileo, Newton, and others made rational thinking the rule, and with that devitalised the planet and all its living creatures, with the exception of the human.

The thousandfold languages of the natural world became inaudible to many humans.

In the past, everything (even for non-Indigenous people) had a “spirit,” an anima (the main idea behind animism). But when science silenced these different languages, our brains became adept at creating predictive models of reality and we gave up what neuroscientists and psychologists call “magical thinking.”

The modern ideal of knowledge is to describe and explain the world without recourse to the anima—spirit, intention, subject, emotion, consciousness, magic, whatever one chooses to call it.

The ideology of modern science is the complete de-spiritualisation or disenchantment of reality.

One day, perhaps, with all the advances in biogenetic research, we will even manage to do without the spirit in the case of humans themselves.

A Different Future: The Radical Spiritualisation of the World

I see Indigenous cosmologies and knowledge as betting precisely on the opposite: on the radical spiritualisation of the world.

Every element of the world is endowed with intentionality and sociability, forming their own unique cultures, what Viveiros de Castro calls the multiplicity of cultures. In such a cosmology, every being comes into being through relations.

And this is reflected in the many languages used to communicate with other beings: painting, dancing, chanting, emitting sounds, dreaming. In some forms of art, it is almost like you can only truly speak with the other if you also become the other.

So how can we re-learn how to speak these different languages?

I think we probably need a spiritual turn, once for different Indigenous groups the spirit is the one that is able to speak these plural languages.

And I think this is already happening: many Westerners are increasingly engaging with Indigenous spiritual practices and other spiritual practices such as yoga, meditation, and so on. Of course there are many complex issues related to such a move that would require another essay to analyse, but still, it is happening.

Dreams, Darkness, and Nourishment

But let us go back to the dark, the original cosmic force.

Dreams, for example, are a great part of Indigenous spiritualities, and another way our spirit speaks. And I think we have not been able to dream anymore in our society. How can we dream if we are a society that does not sleep?

Indigenous writer Cristine Takuá (Maxacali) reminds us that nourishment is not only physical. Food feeds the body, but dreams feed the spirit. When we stop dreaming, the soul becomes anemic.

Carlos Papá, a spiritual leader of the Guarani people, teaches that healing and dreaming come from embracing darkness, the same darkness that once held us in the womb. When we close our eyes to pray or rest, we return to that sacred space where the spirit is nourished. Darkness, in that sense, is not absence but presence. When we return to that darkness, we awaken the outer darkness from which we all came: the cosmic darkness.

From Concepts to Practice: What Would It Take?

Many concepts and efforts circulate today: pluriverse, ontological turn, unlearning, rewilding, regenerating, decolonizing, multispecies justice, conviviality, degrowth, living well, relationality, the future is ancestral. But I wonder what we need to do to put them more into practice.

Maybe we need to rediscover the darkness, the same darkness that originated us, the cosmos, and the space within us. From that space, we could unlearn some of our practices and beliefs and remember who we are.

I do think we are walking in that direction somehow, with all the recognition science is giving to what Indigenous peoples have been talking about for millennia. Meanwhile, the more we want to debate, to prove, to question their ideas, we also lose time. Time that is so precious to make the changes we need to make so we can be fair with future generations.

Finally spirituality and science—despite what we’ve been taught—are not as different as they seem. Both seek to understand ourselves, society, nature, the universe, and even the pluriverse. We can think of them as complementary ways of inquiry, and it is time to bring spirituality and science into dialogue.

So I will leave you with one last reflection on remembering who we are. If we are stardust, if the rocks that shaped our planet carry the same minerals we now refine into the infrastructures of artificial intelligence, then AI is not only a cultural or technical artifact, but also a continuation of a much older, cosmological lineage. This makes me wonder: how much of AI’s language is truly “artificial,” and how much is the universe speaking back through new forms of matter and code? In that sense, AI is already a pluriverse in itself: a shifting assemblage of minerals, histories, human intentions, and more-than-human forces, co-producing worlds.

Image Credits:

1.Pioneer plague - NASA

2.Golden Area by SSIN

3.Hueco Guacamalla by Abel Rodriguez

4.Spirale d'or by by Bassam Geitani

5.Yube Inu Yube Shanu by MAHKU (Huni Kuin Artists Movement)

76.Zirkus (Circus) by Unica Zürn, 1956

Fernanda Gebara is a mother, writer, scientist, and lifelong learner, raised between Brazil’s Atlantic Forest and the city of Rio de Janeiro. With two decades of experience working on Indigenous rights, biodiversity conservation, climate change, and behaviour change, her work focuses on weaving Indigenous and scientific knowledges and supporting Indigenous communities in sharing their cosmologies. She collaborates with the Yorenka Tasorentsi Institute and the Runyn Pupykary Yawanawá Institute to support Indigenous elders in creating an independent framework to preserve ancestral knowledge for future generations.

.jpg)

_%20by%20Unica%20Zu%CC%88rn%2C%201956.jpg)

BY FERNANDA GEBARA

Remembering Who We Are: From “Universe” to Pluriverse

I want to start this essay by remembering who we are, by remembering our own story.

If you trace your lineage back, generation by generation, you quickly reach a simple and unsettling realization: you are related to far more beings than your family tree can hold. Go back far enough and you are connected to every human who has ever lived and to every human alive today.

But the story doesn’t begin with humans.

To remember who we are, our lineage has to widen: to animals, birds, insects; to plants, trees, grasses, and waterborne vegetation; and further still, to the rocks, rivers, and mountains that form the Earth. Until our ancestry becomes universal.

The elements that make up our bodies and our world were forged in stars. The universe is not a distant “out there”; it is the long archive of our deepest lineage. We are stardust: animated by ancient forces that travelled through countless forms before arriving, briefly, as us.

So when we speak of the “universe” we are not speaking in abstractions. We are speaking of kinship. Of how the cosmos, matter, life, and intelligence (human and more-than-human, ancestral and artificial) are entangled in the same deep history.

When “Universe” Became a Scientific Language

By the 17th century, the “universe” became part of the language of modern science, especially after Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica (1687), which described a mechanistic universe functioning like a clock, ruled by universal laws of motion and gravity.

In the 1970s, humanity made its first deliberate attempts to communicate with other beings in the cosmos, possible extraterrestrial intelligences, through two NASA missions curated by Carl Sagan. Both carried messages from Earth designed in the language of science and mathematics, using symbols such as hydrogen atoms, binary numbers, and diagrams of our solar system.

These projects revealed something important: how deeply we relied on the epistemic framework of modern science (more specifically mathematics and physics) as if it were the only language capable of representing “the all,” the grammar through which reality is made intelligible.

Language as World-Making

As Jacques Lacan reminds us, language structures our reality: it is not merely a tool for communication, but the very framework through which we experience the world. He also compared language to mythology as a necessary construct of understanding.

And here I want to invite you to think about language in terms of the diverse ways we can speak with, and not just speak about.

Aníbal Quijano and Walter Mignolo argue that modernity’s so-called universal reason has always been entangled with coloniality. In this process, Europe’s scientific and philosophical frameworks were established as the only legitimate language of knowledge, imposing a single epistemic grammar and silencing other ontologies that were still dominant in the Americas before colonisation, especially Indigenous ones.

The belief that physics stands as the “mother” and ultimate model of all sciences - the one true Science—still endures. As James Watson once said: “What is not physics is mere social work.” In other words, knowledge that cannot be expressed through the mathematical language of physics is dismissed as unscientific.

So: what happens when one grammar or language claims the right to speak for reality itself? This is specially important in a moment where artificial intelligence (AI) is speaking for many.

The Pluriverse: Many grammars, many worlds

The discussion of many grammars, many languages, many worlds and “worldings” as ways of resisting dominant global world-making approaches could be traced back to William James. James coined the term pluriverse in 1907, proposing a reality made not of a single, unified world but of many worlds in the making.

Since then, pluriverse has travelled across different conversations, especially decolonial thought and cosmopolitics. In decolonial debates, the pluriverse is often described as a “world of worlds”: a direct challenge to the idea of the universe as one universal order, and an affirmation of world-making practices that exceed Western science.

Indigenous Cosmologies: The Sun Across Worlds

I want to share here some Indigenous beliefs, trying to link them to the pluriverse.

Ashaninka: Seeing Through Spirit

For the Ashaninka, Pawa—the Creator—brought into being the Sun (Oriya) and numerous invisible beings, referred to as spirits, who were entrusted with shaping the planets and the universe. Pawa gave the Sun a symbolic crown, marking him as co-creator. The Ashaninka headdress, resembling a crown, recalls this original gesture and embodies the people’s connection to the creative force of Pawa and the Sun.

The Sun is understood as a traveler, in perpetual movement, never resting, continually engaged in the work of creation alongside spiritual beings.

However, according to the Ashaninka, the eyes of contemporary humans can no longer perceive these beings. To see them, one must be spiritually connected, because perception occurs through the mind or spirit rather than through the physical senses. According to Moyses Ashaninka, human eyes can perceive only matter, and therefore cannot access the primordial time when the planet was conceived.

The Ashaninka conceive the world as composed of two principal realms: the material and the spiritual. Among them, the spiritual is considered the stronger, as it maintains the balance and continuity of the material world. Without care for the spiritual dimension, material life loses harmony and well-being.

Huni Kuin: Plants That Heal the Spirit

For the Huni Kuin, the Sun—called Bari—once lived in an enchanted and sacred state, resting very close to the Earth. It spoke with humans and with nature. And then at some point the Sun rose high into the sky.

The Sun gave them medicinal plants that carry the meaning of his name: Bari. These are plants for healing the spirit: for purification, bathing, eye medicine, inhalation, and cure.

Guarani: Words, Love, and Song to begin with

For the Guarani, the Sun is called Kuaray. Nhamandu, the creator, emerges from the primordial night, dwelling within the primordial wind. From Nhamandu’s wisdom, from his flame and his divine mist, are born the beautiful words (ayu rapyta). After that, he creates the source of infinite love (mborayu miri) and the divine song (mborai). And only then does he conceive his son: Kuaray, the Sun, destined to be the father of spirits (nhee).

So here we have the creation of words, love, and song before the Sun and all other spirits, showing that for the Guarani, words, love, and songs are primary languages of the cosmos.

The Enlightenment: Silencing of a Thousandfold World

The Sun plays a fundamental role in these cosmologies, as it plays also in Western science. They also recognize the dark, the long night, this cosmic being that “created” the Sun and the spirits.

But we all know that during the Enlightenment—which is literally related to the light, to illuminism—Descartes, Galileo, Newton, and others made rational thinking the rule, and with that devitalised the planet and all its living creatures, with the exception of the human.

The thousandfold languages of the natural world became inaudible to many humans.

In the past, everything (even for non-Indigenous people) had a “spirit,” an anima (the main idea behind animism). But when science silenced these different languages, our brains became adept at creating predictive models of reality and we gave up what neuroscientists and psychologists call “magical thinking.”

The modern ideal of knowledge is to describe and explain the world without recourse to the anima—spirit, intention, subject, emotion, consciousness, magic, whatever one chooses to call it.

The ideology of modern science is the complete de-spiritualisation or disenchantment of reality.

One day, perhaps, with all the advances in biogenetic research, we will even manage to do without the spirit in the case of humans themselves.

A Different Future: The Radical Spiritualisation of the World

I see Indigenous cosmologies and knowledge as betting precisely on the opposite: on the radical spiritualisation of the world.

Every element of the world is endowed with intentionality and sociability, forming their own unique cultures, what Viveiros de Castro calls the multiplicity of cultures. In such a cosmology, every being comes into being through relations.

And this is reflected in the many languages used to communicate with other beings: painting, dancing, chanting, emitting sounds, dreaming. In some forms of art, it is almost like you can only truly speak with the other if you also become the other.

So how can we re-learn how to speak these different languages?

I think we probably need a spiritual turn, once for different Indigenous groups the spirit is the one that is able to speak these plural languages.

And I think this is already happening: many Westerners are increasingly engaging with Indigenous spiritual practices and other spiritual practices such as yoga, meditation, and so on. Of course there are many complex issues related to such a move that would require another essay to analyse, but still, it is happening.

Dreams, Darkness, and Nourishment

But let us go back to the dark, the original cosmic force.

Dreams, for example, are a great part of Indigenous spiritualities, and another way our spirit speaks. And I think we have not been able to dream anymore in our society. How can we dream if we are a society that does not sleep?

Indigenous writer Cristine Takuá (Maxacali) reminds us that nourishment is not only physical. Food feeds the body, but dreams feed the spirit. When we stop dreaming, the soul becomes anemic.

Carlos Papá, a spiritual leader of the Guarani people, teaches that healing and dreaming come from embracing darkness, the same darkness that once held us in the womb. When we close our eyes to pray or rest, we return to that sacred space where the spirit is nourished. Darkness, in that sense, is not absence but presence. When we return to that darkness, we awaken the outer darkness from which we all came: the cosmic darkness.

From Concepts to Practice: What Would It Take?

Many concepts and efforts circulate today: pluriverse, ontological turn, unlearning, rewilding, regenerating, decolonizing, multispecies justice, conviviality, degrowth, living well, relationality, the future is ancestral. But I wonder what we need to do to put them more into practice.

Maybe we need to rediscover the darkness, the same darkness that originated us, the cosmos, and the space within us. From that space, we could unlearn some of our practices and beliefs and remember who we are.

I do think we are walking in that direction somehow, with all the recognition science is giving to what Indigenous peoples have been talking about for millennia. Meanwhile, the more we want to debate, to prove, to question their ideas, we also lose time. Time that is so precious to make the changes we need to make so we can be fair with future generations.

Finally spirituality and science—despite what we’ve been taught—are not as different as they seem. Both seek to understand ourselves, society, nature, the universe, and even the pluriverse. We can think of them as complementary ways of inquiry, and it is time to bring spirituality and science into dialogue.

So I will leave you with one last reflection on remembering who we are. If we are stardust, if the rocks that shaped our planet carry the same minerals we now refine into the infrastructures of artificial intelligence, then AI is not only a cultural or technical artifact, but also a continuation of a much older, cosmological lineage. This makes me wonder: how much of AI’s language is truly “artificial,” and how much is the universe speaking back through new forms of matter and code? In that sense, AI is already a pluriverse in itself: a shifting assemblage of minerals, histories, human intentions, and more-than-human forces, co-producing worlds.

Image Credits:

1.Pioneer plague - NASA

2.Golden Area by SSIN

3.Hueco Guacamalla by Abel Rodriguez

4.Spirale d'or by by Bassam Geitani

5.Yube Inu Yube Shanu by MAHKU (Huni Kuin Artists Movement)

76.Zirkus (Circus) by Unica Zürn, 1956

Remembering Who We Are: From “Universe” to Pluriverse

I want to start this essay by remembering who we are, by remembering our own story.

If you trace your lineage back, generation by generation, you quickly reach a simple and unsettling realization: you are related to far more beings than your family tree can hold. Go back far enough and you are connected to every human who has ever lived and to every human alive today.

But the story doesn’t begin with humans.

To remember who we are, our lineage has to widen: to animals, birds, insects; to plants, trees, grasses, and waterborne vegetation; and further still, to the rocks, rivers, and mountains that form the Earth. Until our ancestry becomes universal.

The elements that make up our bodies and our world were forged in stars. The universe is not a distant “out there”; it is the long archive of our deepest lineage. We are stardust: animated by ancient forces that travelled through countless forms before arriving, briefly, as us.

So when we speak of the “universe” we are not speaking in abstractions. We are speaking of kinship. Of how the cosmos, matter, life, and intelligence (human and more-than-human, ancestral and artificial) are entangled in the same deep history.

When “Universe” Became a Scientific Language

By the 17th century, the “universe” became part of the language of modern science, especially after Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica (1687), which described a mechanistic universe functioning like a clock, ruled by universal laws of motion and gravity.

In the 1970s, humanity made its first deliberate attempts to communicate with other beings in the cosmos, possible extraterrestrial intelligences, through two NASA missions curated by Carl Sagan. Both carried messages from Earth designed in the language of science and mathematics, using symbols such as hydrogen atoms, binary numbers, and diagrams of our solar system.

These projects revealed something important: how deeply we relied on the epistemic framework of modern science (more specifically mathematics and physics) as if it were the only language capable of representing “the all,” the grammar through which reality is made intelligible.

Language as World-Making

As Jacques Lacan reminds us, language structures our reality: it is not merely a tool for communication, but the very framework through which we experience the world. He also compared language to mythology as a necessary construct of understanding.

And here I want to invite you to think about language in terms of the diverse ways we can speak with, and not just speak about.

Aníbal Quijano and Walter Mignolo argue that modernity’s so-called universal reason has always been entangled with coloniality. In this process, Europe’s scientific and philosophical frameworks were established as the only legitimate language of knowledge, imposing a single epistemic grammar and silencing other ontologies that were still dominant in the Americas before colonisation, especially Indigenous ones.

The belief that physics stands as the “mother” and ultimate model of all sciences - the one true Science—still endures. As James Watson once said: “What is not physics is mere social work.” In other words, knowledge that cannot be expressed through the mathematical language of physics is dismissed as unscientific.

So: what happens when one grammar or language claims the right to speak for reality itself? This is specially important in a moment where artificial intelligence (AI) is speaking for many.

The Pluriverse: Many grammars, many worlds

The discussion of many grammars, many languages, many worlds and “worldings” as ways of resisting dominant global world-making approaches could be traced back to William James. James coined the term pluriverse in 1907, proposing a reality made not of a single, unified world but of many worlds in the making.

Since then, pluriverse has travelled across different conversations, especially decolonial thought and cosmopolitics. In decolonial debates, the pluriverse is often described as a “world of worlds”: a direct challenge to the idea of the universe as one universal order, and an affirmation of world-making practices that exceed Western science.

Indigenous Cosmologies: The Sun Across Worlds

I want to share here some Indigenous beliefs, trying to link them to the pluriverse.

Ashaninka: Seeing Through Spirit

For the Ashaninka, Pawa—the Creator—brought into being the Sun (Oriya) and numerous invisible beings, referred to as spirits, who were entrusted with shaping the planets and the universe. Pawa gave the Sun a symbolic crown, marking him as co-creator. The Ashaninka headdress, resembling a crown, recalls this original gesture and embodies the people’s connection to the creative force of Pawa and the Sun.

The Sun is understood as a traveler, in perpetual movement, never resting, continually engaged in the work of creation alongside spiritual beings.

However, according to the Ashaninka, the eyes of contemporary humans can no longer perceive these beings. To see them, one must be spiritually connected, because perception occurs through the mind or spirit rather than through the physical senses. According to Moyses Ashaninka, human eyes can perceive only matter, and therefore cannot access the primordial time when the planet was conceived.

The Ashaninka conceive the world as composed of two principal realms: the material and the spiritual. Among them, the spiritual is considered the stronger, as it maintains the balance and continuity of the material world. Without care for the spiritual dimension, material life loses harmony and well-being.

Huni Kuin: Plants That Heal the Spirit

For the Huni Kuin, the Sun—called Bari—once lived in an enchanted and sacred state, resting very close to the Earth. It spoke with humans and with nature. And then at some point the Sun rose high into the sky.

The Sun gave them medicinal plants that carry the meaning of his name: Bari. These are plants for healing the spirit: for purification, bathing, eye medicine, inhalation, and cure.

Guarani: Words, Love, and Song to begin with

For the Guarani, the Sun is called Kuaray. Nhamandu, the creator, emerges from the primordial night, dwelling within the primordial wind. From Nhamandu’s wisdom, from his flame and his divine mist, are born the beautiful words (ayu rapyta). After that, he creates the source of infinite love (mborayu miri) and the divine song (mborai). And only then does he conceive his son: Kuaray, the Sun, destined to be the father of spirits (nhee).

So here we have the creation of words, love, and song before the Sun and all other spirits, showing that for the Guarani, words, love, and songs are primary languages of the cosmos.

The Enlightenment: Silencing of a Thousandfold World

The Sun plays a fundamental role in these cosmologies, as it plays also in Western science. They also recognize the dark, the long night, this cosmic being that “created” the Sun and the spirits.

But we all know that during the Enlightenment—which is literally related to the light, to illuminism—Descartes, Galileo, Newton, and others made rational thinking the rule, and with that devitalised the planet and all its living creatures, with the exception of the human.

The thousandfold languages of the natural world became inaudible to many humans.

In the past, everything (even for non-Indigenous people) had a “spirit,” an anima (the main idea behind animism). But when science silenced these different languages, our brains became adept at creating predictive models of reality and we gave up what neuroscientists and psychologists call “magical thinking.”

The modern ideal of knowledge is to describe and explain the world without recourse to the anima—spirit, intention, subject, emotion, consciousness, magic, whatever one chooses to call it.

The ideology of modern science is the complete de-spiritualisation or disenchantment of reality.

One day, perhaps, with all the advances in biogenetic research, we will even manage to do without the spirit in the case of humans themselves.

A Different Future: The Radical Spiritualisation of the World

I see Indigenous cosmologies and knowledge as betting precisely on the opposite: on the radical spiritualisation of the world.

Every element of the world is endowed with intentionality and sociability, forming their own unique cultures, what Viveiros de Castro calls the multiplicity of cultures. In such a cosmology, every being comes into being through relations.

And this is reflected in the many languages used to communicate with other beings: painting, dancing, chanting, emitting sounds, dreaming. In some forms of art, it is almost like you can only truly speak with the other if you also become the other.

So how can we re-learn how to speak these different languages?

I think we probably need a spiritual turn, once for different Indigenous groups the spirit is the one that is able to speak these plural languages.

And I think this is already happening: many Westerners are increasingly engaging with Indigenous spiritual practices and other spiritual practices such as yoga, meditation, and so on. Of course there are many complex issues related to such a move that would require another essay to analyse, but still, it is happening.

Dreams, Darkness, and Nourishment

But let us go back to the dark, the original cosmic force.

Dreams, for example, are a great part of Indigenous spiritualities, and another way our spirit speaks. And I think we have not been able to dream anymore in our society. How can we dream if we are a society that does not sleep?

Indigenous writer Cristine Takuá (Maxacali) reminds us that nourishment is not only physical. Food feeds the body, but dreams feed the spirit. When we stop dreaming, the soul becomes anemic.

Carlos Papá, a spiritual leader of the Guarani people, teaches that healing and dreaming come from embracing darkness, the same darkness that once held us in the womb. When we close our eyes to pray or rest, we return to that sacred space where the spirit is nourished. Darkness, in that sense, is not absence but presence. When we return to that darkness, we awaken the outer darkness from which we all came: the cosmic darkness.

From Concepts to Practice: What Would It Take?

Many concepts and efforts circulate today: pluriverse, ontological turn, unlearning, rewilding, regenerating, decolonizing, multispecies justice, conviviality, degrowth, living well, relationality, the future is ancestral. But I wonder what we need to do to put them more into practice.

Maybe we need to rediscover the darkness, the same darkness that originated us, the cosmos, and the space within us. From that space, we could unlearn some of our practices and beliefs and remember who we are.

I do think we are walking in that direction somehow, with all the recognition science is giving to what Indigenous peoples have been talking about for millennia. Meanwhile, the more we want to debate, to prove, to question their ideas, we also lose time. Time that is so precious to make the changes we need to make so we can be fair with future generations.

Finally spirituality and science—despite what we’ve been taught—are not as different as they seem. Both seek to understand ourselves, society, nature, the universe, and even the pluriverse. We can think of them as complementary ways of inquiry, and it is time to bring spirituality and science into dialogue.

So I will leave you with one last reflection on remembering who we are. If we are stardust, if the rocks that shaped our planet carry the same minerals we now refine into the infrastructures of artificial intelligence, then AI is not only a cultural or technical artifact, but also a continuation of a much older, cosmological lineage. This makes me wonder: how much of AI’s language is truly “artificial,” and how much is the universe speaking back through new forms of matter and code? In that sense, AI is already a pluriverse in itself: a shifting assemblage of minerals, histories, human intentions, and more-than-human forces, co-producing worlds.

Image Credits:

1.Pioneer plague - NASA

2.Golden Area by SSIN

3.Hueco Guacamalla by Abel Rodriguez

4.Spirale d'or by by Bassam Geitani

5.Yube Inu Yube Shanu by MAHKU (Huni Kuin Artists Movement)

76.Zirkus (Circus) by Unica Zürn, 1956

.jpg)

_%20by%20Unica%20Zu%CC%88rn%2C%201956.jpg)

Fernanda Gebara is a mother, writer, scientist, and lifelong learner, raised between Brazil’s Atlantic Forest and the city of Rio de Janeiro. With two decades of experience working on Indigenous rights, biodiversity conservation, climate change, and behaviour change, her work focuses on weaving Indigenous and scientific knowledges and supporting Indigenous communities in sharing their cosmologies. She collaborates with the Yorenka Tasorentsi Institute and the Runyn Pupykary Yawanawá Institute to support Indigenous elders in creating an independent framework to preserve ancestral knowledge for future generations.

BY FERNANDA GEBARA

Remembering Who We Are: From “Universe” to Pluriverse

I want to start this essay by remembering who we are, by remembering our own story.

If you trace your lineage back, generation by generation, you quickly reach a simple and unsettling realization: you are related to far more beings than your family tree can hold. Go back far enough and you are connected to every human who has ever lived and to every human alive today.

But the story doesn’t begin with humans.

To remember who we are, our lineage has to widen: to animals, birds, insects; to plants, trees, grasses, and waterborne vegetation; and further still, to the rocks, rivers, and mountains that form the Earth. Until our ancestry becomes universal.

The elements that make up our bodies and our world were forged in stars. The universe is not a distant “out there”; it is the long archive of our deepest lineage. We are stardust: animated by ancient forces that travelled through countless forms before arriving, briefly, as us.

So when we speak of the “universe” we are not speaking in abstractions. We are speaking of kinship. Of how the cosmos, matter, life, and intelligence (human and more-than-human, ancestral and artificial) are entangled in the same deep history.

When “Universe” Became a Scientific Language

By the 17th century, the “universe” became part of the language of modern science, especially after Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica (1687), which described a mechanistic universe functioning like a clock, ruled by universal laws of motion and gravity.

In the 1970s, humanity made its first deliberate attempts to communicate with other beings in the cosmos, possible extraterrestrial intelligences, through two NASA missions curated by Carl Sagan. Both carried messages from Earth designed in the language of science and mathematics, using symbols such as hydrogen atoms, binary numbers, and diagrams of our solar system.

These projects revealed something important: how deeply we relied on the epistemic framework of modern science (more specifically mathematics and physics) as if it were the only language capable of representing “the all,” the grammar through which reality is made intelligible.

Language as World-Making

As Jacques Lacan reminds us, language structures our reality: it is not merely a tool for communication, but the very framework through which we experience the world. He also compared language to mythology as a necessary construct of understanding.

And here I want to invite you to think about language in terms of the diverse ways we can speak with, and not just speak about.

Aníbal Quijano and Walter Mignolo argue that modernity’s so-called universal reason has always been entangled with coloniality. In this process, Europe’s scientific and philosophical frameworks were established as the only legitimate language of knowledge, imposing a single epistemic grammar and silencing other ontologies that were still dominant in the Americas before colonisation, especially Indigenous ones.

The belief that physics stands as the “mother” and ultimate model of all sciences - the one true Science—still endures. As James Watson once said: “What is not physics is mere social work.” In other words, knowledge that cannot be expressed through the mathematical language of physics is dismissed as unscientific.

So: what happens when one grammar or language claims the right to speak for reality itself? This is specially important in a moment where artificial intelligence (AI) is speaking for many.

The Pluriverse: Many grammars, many worlds

The discussion of many grammars, many languages, many worlds and “worldings” as ways of resisting dominant global world-making approaches could be traced back to William James. James coined the term pluriverse in 1907, proposing a reality made not of a single, unified world but of many worlds in the making.

Since then, pluriverse has travelled across different conversations, especially decolonial thought and cosmopolitics. In decolonial debates, the pluriverse is often described as a “world of worlds”: a direct challenge to the idea of the universe as one universal order, and an affirmation of world-making practices that exceed Western science.

Indigenous Cosmologies: The Sun Across Worlds

I want to share here some Indigenous beliefs, trying to link them to the pluriverse.

Ashaninka: Seeing Through Spirit

For the Ashaninka, Pawa—the Creator—brought into being the Sun (Oriya) and numerous invisible beings, referred to as spirits, who were entrusted with shaping the planets and the universe. Pawa gave the Sun a symbolic crown, marking him as co-creator. The Ashaninka headdress, resembling a crown, recalls this original gesture and embodies the people’s connection to the creative force of Pawa and the Sun.

The Sun is understood as a traveler, in perpetual movement, never resting, continually engaged in the work of creation alongside spiritual beings.

However, according to the Ashaninka, the eyes of contemporary humans can no longer perceive these beings. To see them, one must be spiritually connected, because perception occurs through the mind or spirit rather than through the physical senses. According to Moyses Ashaninka, human eyes can perceive only matter, and therefore cannot access the primordial time when the planet was conceived.

The Ashaninka conceive the world as composed of two principal realms: the material and the spiritual. Among them, the spiritual is considered the stronger, as it maintains the balance and continuity of the material world. Without care for the spiritual dimension, material life loses harmony and well-being.

Huni Kuin: Plants That Heal the Spirit

For the Huni Kuin, the Sun—called Bari—once lived in an enchanted and sacred state, resting very close to the Earth. It spoke with humans and with nature. And then at some point the Sun rose high into the sky.

The Sun gave them medicinal plants that carry the meaning of his name: Bari. These are plants for healing the spirit: for purification, bathing, eye medicine, inhalation, and cure.

Guarani: Words, Love, and Song to begin with

For the Guarani, the Sun is called Kuaray. Nhamandu, the creator, emerges from the primordial night, dwelling within the primordial wind. From Nhamandu’s wisdom, from his flame and his divine mist, are born the beautiful words (ayu rapyta). After that, he creates the source of infinite love (mborayu miri) and the divine song (mborai). And only then does he conceive his son: Kuaray, the Sun, destined to be the father of spirits (nhee).

So here we have the creation of words, love, and song before the Sun and all other spirits, showing that for the Guarani, words, love, and songs are primary languages of the cosmos.

The Enlightenment: Silencing of a Thousandfold World

The Sun plays a fundamental role in these cosmologies, as it plays also in Western science. They also recognize the dark, the long night, this cosmic being that “created” the Sun and the spirits.

But we all know that during the Enlightenment—which is literally related to the light, to illuminism—Descartes, Galileo, Newton, and others made rational thinking the rule, and with that devitalised the planet and all its living creatures, with the exception of the human.

The thousandfold languages of the natural world became inaudible to many humans.

In the past, everything (even for non-Indigenous people) had a “spirit,” an anima (the main idea behind animism). But when science silenced these different languages, our brains became adept at creating predictive models of reality and we gave up what neuroscientists and psychologists call “magical thinking.”

The modern ideal of knowledge is to describe and explain the world without recourse to the anima—spirit, intention, subject, emotion, consciousness, magic, whatever one chooses to call it.

The ideology of modern science is the complete de-spiritualisation or disenchantment of reality.

One day, perhaps, with all the advances in biogenetic research, we will even manage to do without the spirit in the case of humans themselves.

A Different Future: The Radical Spiritualisation of the World

I see Indigenous cosmologies and knowledge as betting precisely on the opposite: on the radical spiritualisation of the world.

Every element of the world is endowed with intentionality and sociability, forming their own unique cultures, what Viveiros de Castro calls the multiplicity of cultures. In such a cosmology, every being comes into being through relations.

And this is reflected in the many languages used to communicate with other beings: painting, dancing, chanting, emitting sounds, dreaming. In some forms of art, it is almost like you can only truly speak with the other if you also become the other.

So how can we re-learn how to speak these different languages?

I think we probably need a spiritual turn, once for different Indigenous groups the spirit is the one that is able to speak these plural languages.

And I think this is already happening: many Westerners are increasingly engaging with Indigenous spiritual practices and other spiritual practices such as yoga, meditation, and so on. Of course there are many complex issues related to such a move that would require another essay to analyse, but still, it is happening.

Dreams, Darkness, and Nourishment

But let us go back to the dark, the original cosmic force.

Dreams, for example, are a great part of Indigenous spiritualities, and another way our spirit speaks. And I think we have not been able to dream anymore in our society. How can we dream if we are a society that does not sleep?

Indigenous writer Cristine Takuá (Maxacali) reminds us that nourishment is not only physical. Food feeds the body, but dreams feed the spirit. When we stop dreaming, the soul becomes anemic.

Carlos Papá, a spiritual leader of the Guarani people, teaches that healing and dreaming come from embracing darkness, the same darkness that once held us in the womb. When we close our eyes to pray or rest, we return to that sacred space where the spirit is nourished. Darkness, in that sense, is not absence but presence. When we return to that darkness, we awaken the outer darkness from which we all came: the cosmic darkness.

From Concepts to Practice: What Would It Take?

Many concepts and efforts circulate today: pluriverse, ontological turn, unlearning, rewilding, regenerating, decolonizing, multispecies justice, conviviality, degrowth, living well, relationality, the future is ancestral. But I wonder what we need to do to put them more into practice.

Maybe we need to rediscover the darkness, the same darkness that originated us, the cosmos, and the space within us. From that space, we could unlearn some of our practices and beliefs and remember who we are.

I do think we are walking in that direction somehow, with all the recognition science is giving to what Indigenous peoples have been talking about for millennia. Meanwhile, the more we want to debate, to prove, to question their ideas, we also lose time. Time that is so precious to make the changes we need to make so we can be fair with future generations.

Finally spirituality and science—despite what we’ve been taught—are not as different as they seem. Both seek to understand ourselves, society, nature, the universe, and even the pluriverse. We can think of them as complementary ways of inquiry, and it is time to bring spirituality and science into dialogue.

So I will leave you with one last reflection on remembering who we are. If we are stardust, if the rocks that shaped our planet carry the same minerals we now refine into the infrastructures of artificial intelligence, then AI is not only a cultural or technical artifact, but also a continuation of a much older, cosmological lineage. This makes me wonder: how much of AI’s language is truly “artificial,” and how much is the universe speaking back through new forms of matter and code? In that sense, AI is already a pluriverse in itself: a shifting assemblage of minerals, histories, human intentions, and more-than-human forces, co-producing worlds.

Image Credits:

1.Pioneer plague - NASA

2.Golden Area by SSIN

3.Hueco Guacamalla by Abel Rodriguez

4.Spirale d'or by by Bassam Geitani

5.Yube Inu Yube Shanu by MAHKU (Huni Kuin Artists Movement)

76.Zirkus (Circus) by Unica Zürn, 1956

Remembering Who We Are: From “Universe” to Pluriverse

I want to start this essay by remembering who we are, by remembering our own story.

If you trace your lineage back, generation by generation, you quickly reach a simple and unsettling realization: you are related to far more beings than your family tree can hold. Go back far enough and you are connected to every human who has ever lived and to every human alive today.

But the story doesn’t begin with humans.

To remember who we are, our lineage has to widen: to animals, birds, insects; to plants, trees, grasses, and waterborne vegetation; and further still, to the rocks, rivers, and mountains that form the Earth. Until our ancestry becomes universal.

The elements that make up our bodies and our world were forged in stars. The universe is not a distant “out there”; it is the long archive of our deepest lineage. We are stardust: animated by ancient forces that travelled through countless forms before arriving, briefly, as us.

So when we speak of the “universe” we are not speaking in abstractions. We are speaking of kinship. Of how the cosmos, matter, life, and intelligence (human and more-than-human, ancestral and artificial) are entangled in the same deep history.

When “Universe” Became a Scientific Language

By the 17th century, the “universe” became part of the language of modern science, especially after Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica (1687), which described a mechanistic universe functioning like a clock, ruled by universal laws of motion and gravity.

In the 1970s, humanity made its first deliberate attempts to communicate with other beings in the cosmos, possible extraterrestrial intelligences, through two NASA missions curated by Carl Sagan. Both carried messages from Earth designed in the language of science and mathematics, using symbols such as hydrogen atoms, binary numbers, and diagrams of our solar system.

These projects revealed something important: how deeply we relied on the epistemic framework of modern science (more specifically mathematics and physics) as if it were the only language capable of representing “the all,” the grammar through which reality is made intelligible.

Language as World-Making

As Jacques Lacan reminds us, language structures our reality: it is not merely a tool for communication, but the very framework through which we experience the world. He also compared language to mythology as a necessary construct of understanding.

And here I want to invite you to think about language in terms of the diverse ways we can speak with, and not just speak about.

Aníbal Quijano and Walter Mignolo argue that modernity’s so-called universal reason has always been entangled with coloniality. In this process, Europe’s scientific and philosophical frameworks were established as the only legitimate language of knowledge, imposing a single epistemic grammar and silencing other ontologies that were still dominant in the Americas before colonisation, especially Indigenous ones.

The belief that physics stands as the “mother” and ultimate model of all sciences - the one true Science—still endures. As James Watson once said: “What is not physics is mere social work.” In other words, knowledge that cannot be expressed through the mathematical language of physics is dismissed as unscientific.

So: what happens when one grammar or language claims the right to speak for reality itself? This is specially important in a moment where artificial intelligence (AI) is speaking for many.

The Pluriverse: Many grammars, many worlds

The discussion of many grammars, many languages, many worlds and “worldings” as ways of resisting dominant global world-making approaches could be traced back to William James. James coined the term pluriverse in 1907, proposing a reality made not of a single, unified world but of many worlds in the making.

Since then, pluriverse has travelled across different conversations, especially decolonial thought and cosmopolitics. In decolonial debates, the pluriverse is often described as a “world of worlds”: a direct challenge to the idea of the universe as one universal order, and an affirmation of world-making practices that exceed Western science.

Indigenous Cosmologies: The Sun Across Worlds

I want to share here some Indigenous beliefs, trying to link them to the pluriverse.

Ashaninka: Seeing Through Spirit

For the Ashaninka, Pawa—the Creator—brought into being the Sun (Oriya) and numerous invisible beings, referred to as spirits, who were entrusted with shaping the planets and the universe. Pawa gave the Sun a symbolic crown, marking him as co-creator. The Ashaninka headdress, resembling a crown, recalls this original gesture and embodies the people’s connection to the creative force of Pawa and the Sun.

The Sun is understood as a traveler, in perpetual movement, never resting, continually engaged in the work of creation alongside spiritual beings.

However, according to the Ashaninka, the eyes of contemporary humans can no longer perceive these beings. To see them, one must be spiritually connected, because perception occurs through the mind or spirit rather than through the physical senses. According to Moyses Ashaninka, human eyes can perceive only matter, and therefore cannot access the primordial time when the planet was conceived.

The Ashaninka conceive the world as composed of two principal realms: the material and the spiritual. Among them, the spiritual is considered the stronger, as it maintains the balance and continuity of the material world. Without care for the spiritual dimension, material life loses harmony and well-being.

Huni Kuin: Plants That Heal the Spirit

For the Huni Kuin, the Sun—called Bari—once lived in an enchanted and sacred state, resting very close to the Earth. It spoke with humans and with nature. And then at some point the Sun rose high into the sky.

The Sun gave them medicinal plants that carry the meaning of his name: Bari. These are plants for healing the spirit: for purification, bathing, eye medicine, inhalation, and cure.

Guarani: Words, Love, and Song to begin with

For the Guarani, the Sun is called Kuaray. Nhamandu, the creator, emerges from the primordial night, dwelling within the primordial wind. From Nhamandu’s wisdom, from his flame and his divine mist, are born the beautiful words (ayu rapyta). After that, he creates the source of infinite love (mborayu miri) and the divine song (mborai). And only then does he conceive his son: Kuaray, the Sun, destined to be the father of spirits (nhee).

So here we have the creation of words, love, and song before the Sun and all other spirits, showing that for the Guarani, words, love, and songs are primary languages of the cosmos.

The Enlightenment: Silencing of a Thousandfold World

The Sun plays a fundamental role in these cosmologies, as it plays also in Western science. They also recognize the dark, the long night, this cosmic being that “created” the Sun and the spirits.

But we all know that during the Enlightenment—which is literally related to the light, to illuminism—Descartes, Galileo, Newton, and others made rational thinking the rule, and with that devitalised the planet and all its living creatures, with the exception of the human.

The thousandfold languages of the natural world became inaudible to many humans.

In the past, everything (even for non-Indigenous people) had a “spirit,” an anima (the main idea behind animism). But when science silenced these different languages, our brains became adept at creating predictive models of reality and we gave up what neuroscientists and psychologists call “magical thinking.”

The modern ideal of knowledge is to describe and explain the world without recourse to the anima—spirit, intention, subject, emotion, consciousness, magic, whatever one chooses to call it.

The ideology of modern science is the complete de-spiritualisation or disenchantment of reality.

One day, perhaps, with all the advances in biogenetic research, we will even manage to do without the spirit in the case of humans themselves.

A Different Future: The Radical Spiritualisation of the World

I see Indigenous cosmologies and knowledge as betting precisely on the opposite: on the radical spiritualisation of the world.

Every element of the world is endowed with intentionality and sociability, forming their own unique cultures, what Viveiros de Castro calls the multiplicity of cultures. In such a cosmology, every being comes into being through relations.

And this is reflected in the many languages used to communicate with other beings: painting, dancing, chanting, emitting sounds, dreaming. In some forms of art, it is almost like you can only truly speak with the other if you also become the other.

So how can we re-learn how to speak these different languages?

I think we probably need a spiritual turn, once for different Indigenous groups the spirit is the one that is able to speak these plural languages.

And I think this is already happening: many Westerners are increasingly engaging with Indigenous spiritual practices and other spiritual practices such as yoga, meditation, and so on. Of course there are many complex issues related to such a move that would require another essay to analyse, but still, it is happening.

Dreams, Darkness, and Nourishment

But let us go back to the dark, the original cosmic force.

Dreams, for example, are a great part of Indigenous spiritualities, and another way our spirit speaks. And I think we have not been able to dream anymore in our society. How can we dream if we are a society that does not sleep?

Indigenous writer Cristine Takuá (Maxacali) reminds us that nourishment is not only physical. Food feeds the body, but dreams feed the spirit. When we stop dreaming, the soul becomes anemic.

Carlos Papá, a spiritual leader of the Guarani people, teaches that healing and dreaming come from embracing darkness, the same darkness that once held us in the womb. When we close our eyes to pray or rest, we return to that sacred space where the spirit is nourished. Darkness, in that sense, is not absence but presence. When we return to that darkness, we awaken the outer darkness from which we all came: the cosmic darkness.

From Concepts to Practice: What Would It Take?

Many concepts and efforts circulate today: pluriverse, ontological turn, unlearning, rewilding, regenerating, decolonizing, multispecies justice, conviviality, degrowth, living well, relationality, the future is ancestral. But I wonder what we need to do to put them more into practice.

Maybe we need to rediscover the darkness, the same darkness that originated us, the cosmos, and the space within us. From that space, we could unlearn some of our practices and beliefs and remember who we are.

I do think we are walking in that direction somehow, with all the recognition science is giving to what Indigenous peoples have been talking about for millennia. Meanwhile, the more we want to debate, to prove, to question their ideas, we also lose time. Time that is so precious to make the changes we need to make so we can be fair with future generations.

Finally spirituality and science—despite what we’ve been taught—are not as different as they seem. Both seek to understand ourselves, society, nature, the universe, and even the pluriverse. We can think of them as complementary ways of inquiry, and it is time to bring spirituality and science into dialogue.

So I will leave you with one last reflection on remembering who we are. If we are stardust, if the rocks that shaped our planet carry the same minerals we now refine into the infrastructures of artificial intelligence, then AI is not only a cultural or technical artifact, but also a continuation of a much older, cosmological lineage. This makes me wonder: how much of AI’s language is truly “artificial,” and how much is the universe speaking back through new forms of matter and code? In that sense, AI is already a pluriverse in itself: a shifting assemblage of minerals, histories, human intentions, and more-than-human forces, co-producing worlds.

Image Credits:

1.Pioneer plague - NASA

2.Golden Area by SSIN

3.Hueco Guacamalla by Abel Rodriguez

4.Spirale d'or by by Bassam Geitani

5.Yube Inu Yube Shanu by MAHKU (Huni Kuin Artists Movement)

76.Zirkus (Circus) by Unica Zürn, 1956

.jpg)

_%20by%20Unica%20Zu%CC%88rn%2C%201956.jpg)

Fernanda Gebara is a mother, writer, scientist, and lifelong learner, raised between Brazil’s Atlantic Forest and the city of Rio de Janeiro. With two decades of experience working on Indigenous rights, biodiversity conservation, climate change, and behaviour change, her work focuses on weaving Indigenous and scientific knowledges and supporting Indigenous communities in sharing their cosmologies. She collaborates with the Yorenka Tasorentsi Institute and the Runyn Pupykary Yawanawá Institute to support Indigenous elders in creating an independent framework to preserve ancestral knowledge for future generations.

BY FERNANDA GEBARA

Remembering Who We Are: From “Universe” to Pluriverse

I want to start this essay by remembering who we are, by remembering our own story.

If you trace your lineage back, generation by generation, you quickly reach a simple and unsettling realization: you are related to far more beings than your family tree can hold. Go back far enough and you are connected to every human who has ever lived and to every human alive today.

But the story doesn’t begin with humans.

To remember who we are, our lineage has to widen: to animals, birds, insects; to plants, trees, grasses, and waterborne vegetation; and further still, to the rocks, rivers, and mountains that form the Earth. Until our ancestry becomes universal.

The elements that make up our bodies and our world were forged in stars. The universe is not a distant “out there”; it is the long archive of our deepest lineage. We are stardust: animated by ancient forces that travelled through countless forms before arriving, briefly, as us.

So when we speak of the “universe” we are not speaking in abstractions. We are speaking of kinship. Of how the cosmos, matter, life, and intelligence (human and more-than-human, ancestral and artificial) are entangled in the same deep history.

When “Universe” Became a Scientific Language

By the 17th century, the “universe” became part of the language of modern science, especially after Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica (1687), which described a mechanistic universe functioning like a clock, ruled by universal laws of motion and gravity.