INTERVIEW WITH IZ PAEHR

JF - Feeling Virtual begins from lived practices of navigating an inaccessible world rather than retrofitting existing VR systems. How did starting from access reshape what virtual reality could become?

IP - My misfit experiences with VR started with the existing design of the controllers of commercially available VR systems, which are hand-held. Holding a walking stick at the same time makes it laborious to use two controllers at once. Here, my first access hack came in the form of a strap that I wrap around my shoulders and with which I can let the controllers dangle, while also moving with my mobility aid. aStarting from access meant asking questions to other disabled folks, slowing down and testing alternative setups together. I learned from my conversation partners that tactile knowledge is underappreciated in society as well as in technology design. This is why the project moved towards tactile access.

JF -Touch is usually removed from archival encounters in the name of preservation. What happened when you reintroduced touch as a way of knowing the Salzburg Festival Archive?

IP - I continue to be grateful that the team of the Salzburg Festival Archive facilitated my tactile access to their collections without hesitation. In the process of touching my way through opera and theatre history, I learned that sight is quite limited when it comes to knowing archival materials in detail. Often, touching a dress from the costume storage would reveal a hidden knot of embroidery yarn hidden underneath a corsage, or would make apparent that a diamond was made from plastic. I also realized how limited my own language was when trying to put these tactile experiences into words, an experience that resonates with the writings of blind scholars such as Lilian Korner. This is why one outcome of my project is a Tactile Descriptions Workbook that offers guiding questions and tactile sensing exercises to feel out tactile language. Your question on preservation as a reason that materials are kept out of touch is spot on and also concerns archival digitization practices. Many contemporary 3D scanning techniques used by archives follow visual paradigms by scanning outlines of costumes for visual digital representations. My hope is that future preservation does not rely on visual preservation alone, so that we do not lose the rich haptic histories that artifacts can teach us about.

JF - By foregrounding vibration, temperature, resistance, and movement, the project shifts VR away from visual dominance. What kinds of new attentions or intimacies emerged through this multisensorial approach?

IP - During my residency, I took part in a seminar of DeafBlind poet John Lee Clark, who taught me that the goal is not to replace an existing sensory hierarchy with another, but to undo the idea of a hierarchy. Undoing visual dominance meant inviting sensory plurality. In the XR artwork Archive of Touch, the interplay of movement, vibration, resistance and sound creates an intimate experience of being in touch with archival objects. Touch is always relational: You cannot touch without also being touched. In Archive of Touch, every touch creates: sounds, vibrations, descriptions, visual textures. The archival materials from the Salzburg Festival Archive become alive – through our willingness and openness to be in touch with them.

JF - You describe play as fragile, tense, and prone to breakdown. How did failure, slowness, or malfunction become generative forces in the work?

IP - Imagine me in my studio, with vibration motors taped to my knees, fixing bugs on my computer and wishing for the sensations on my skin to finally feel like the silk of an opera dress! I love this question, as it reminds me of the frustrations of slowly and not always successfully working against the technical status quo of VR, as well as the joy of imagining and building controllers that work for many bodies and minds. In a way, this project started out with a failure: Of how commercial VR tech is failing disabled people. And this failure became generative. As the project continued, my prototypes of what a VR experience could feel like failed my disabled test players and me less, but it certainly failed at being what ‘smooth, well working tech’ is imagined as. I keep being very interested in moments of slowness, failure and play when it comes to access making with technology.

JF - Looking ahead, how might starting from crip knowledge and tactile imaginaries transform not just VR, but how we relate to cultural heritage more broadly?

IP - Starting from disabled tactile and remote access knowledges can transform how we think of and use technologies, and how these technologies can facilitate access to cultural heritage. When thinking of remote access, the brilliant work of disabled people at the height of the COVID pandemic comes to mind in sharing knowledges on how to connect online. This work has become part of cultural heritage itself in the form of the Critical Design Lab’s Remote Access Archive. DeafBlind communities use the term Virtual Touch to refer to the ways in which they stay in touch via email listservs. It is time to bring these knowledges in touch with how cultural heritage is commonly preserved and made (in)accessible. I think crip creativity can be a key to overcoming the oftentimes voiced concern that cultural heritage materials cannot be touched by a lot of people without being damaged. Disabled culture teaches us that there are many ways to touch and be in touch with each other and with cultural heritage, that we can hold vulnerability of people and materials together, and that after all, tactile access is something we can invent together, with and without tech.

Image Descriptions:

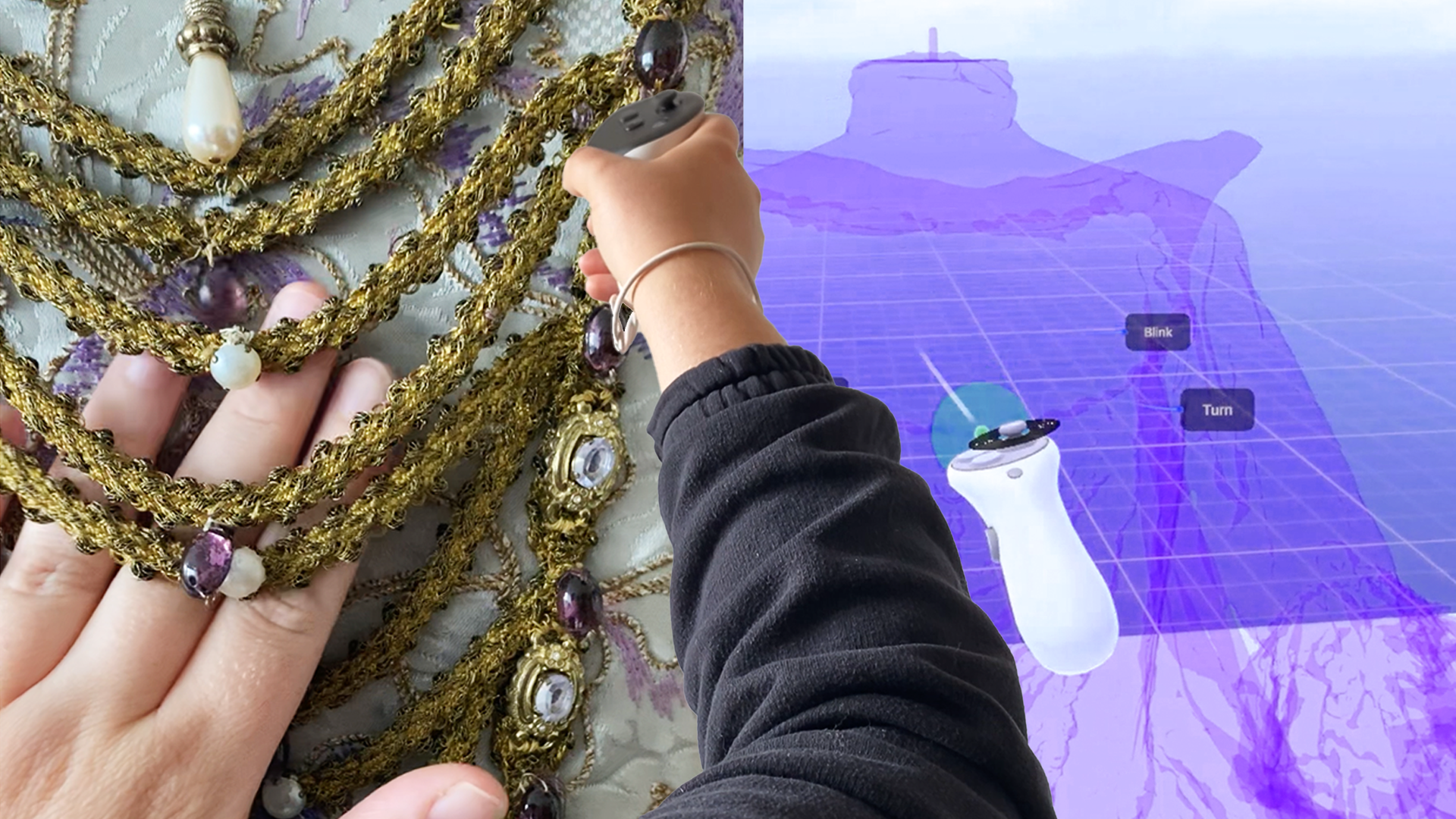

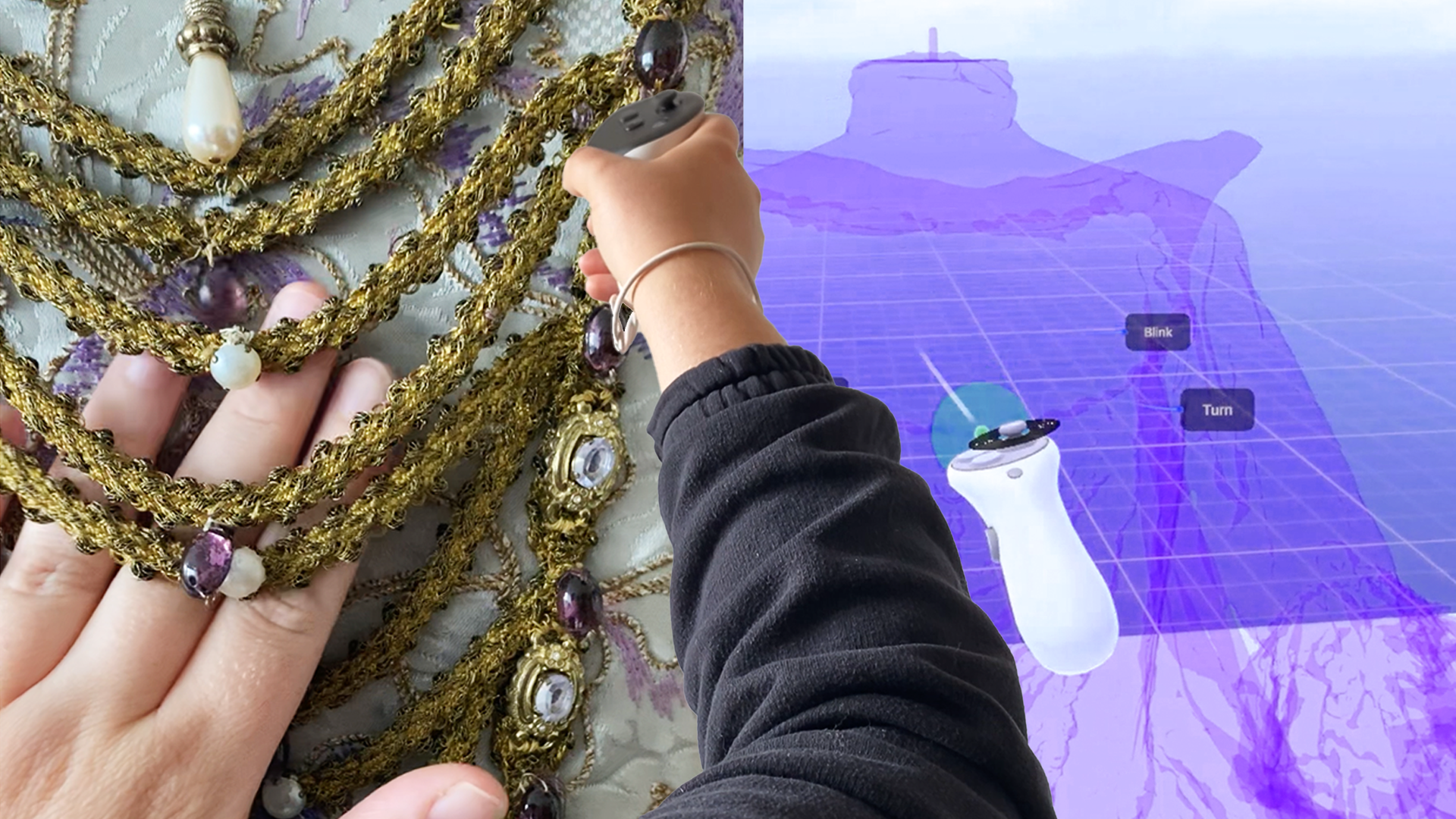

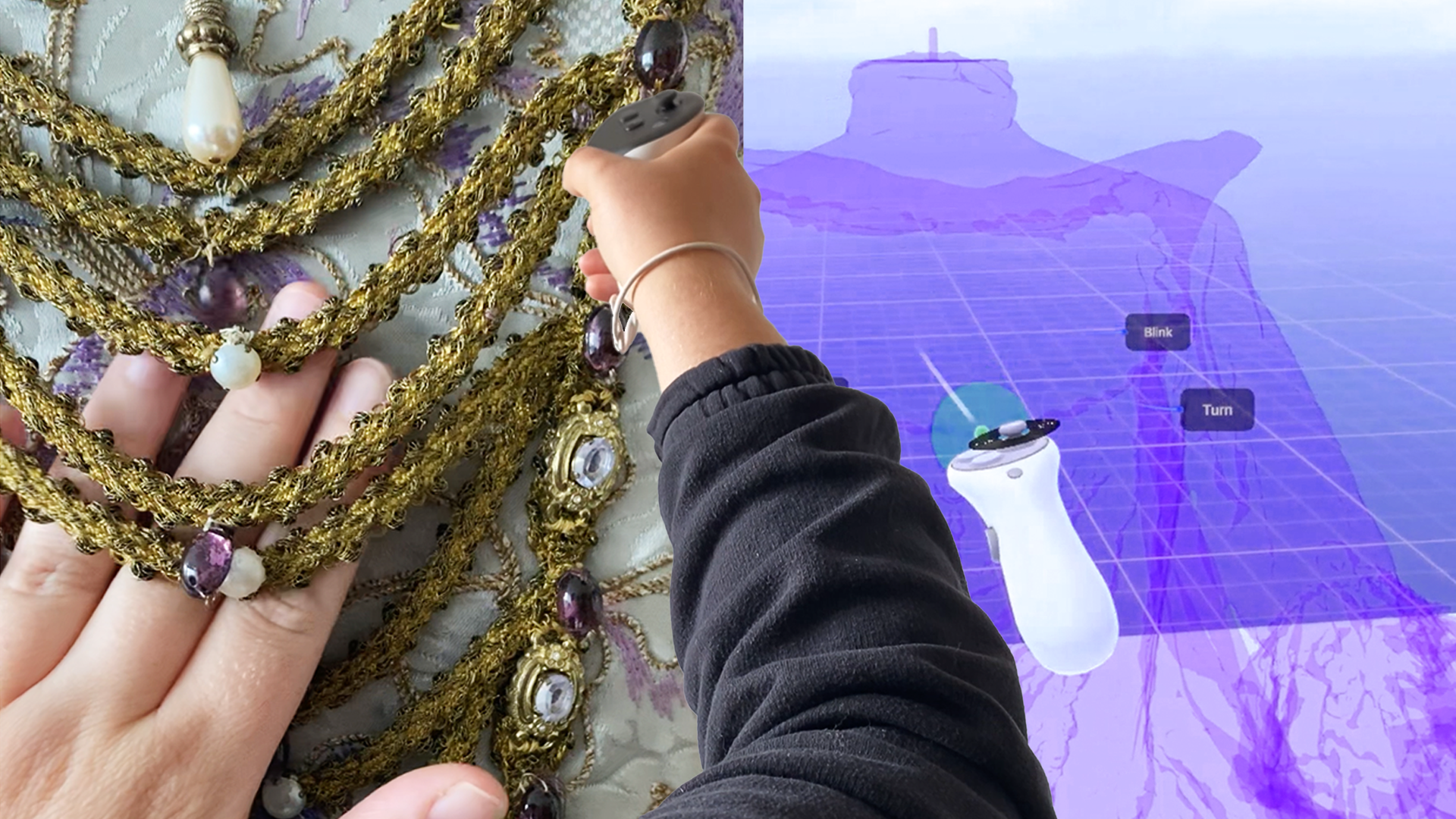

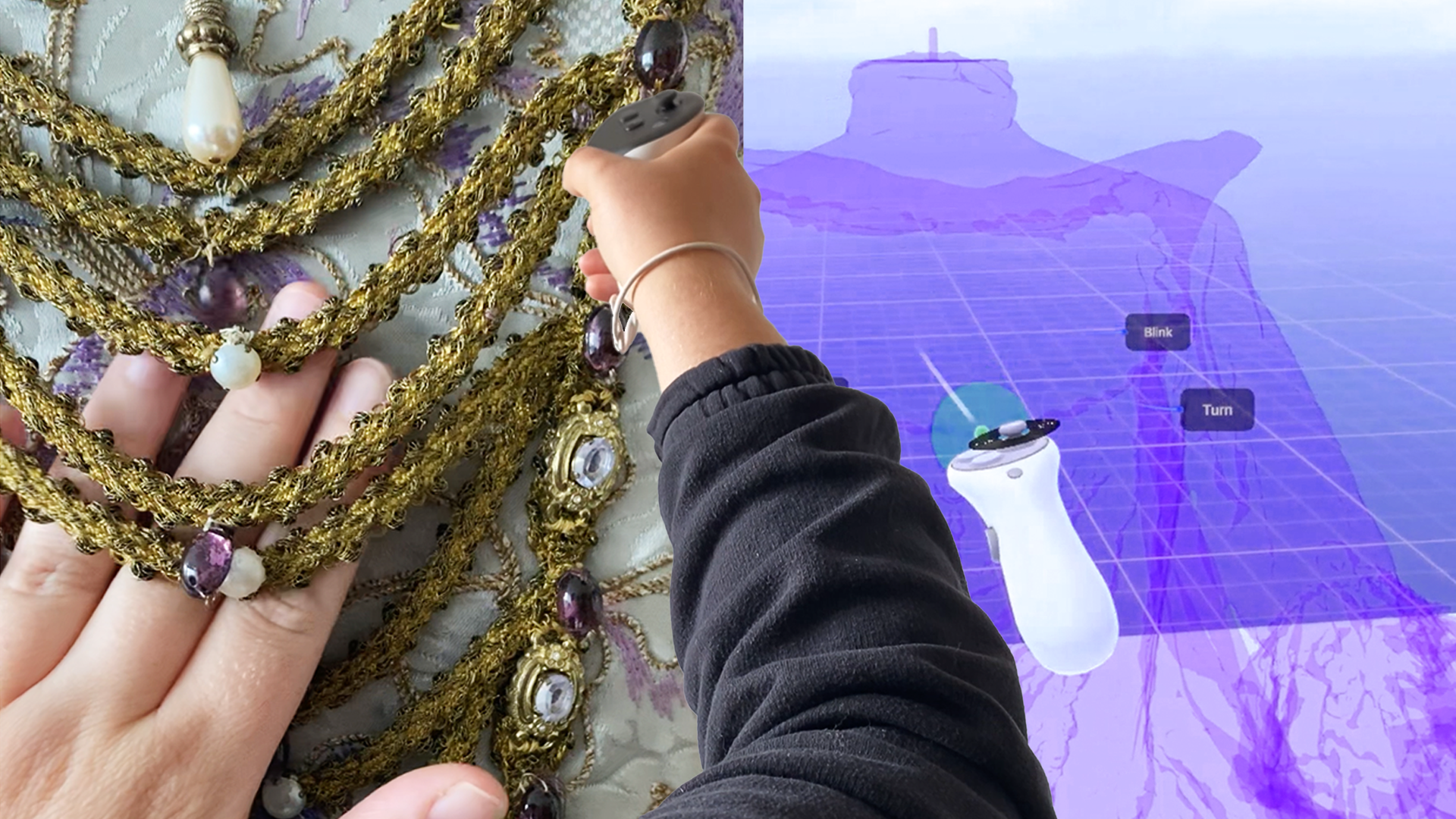

IzPaehr_Collage01: This collage shows touches across modalities: On the left, Iz hand is shown touching the opulent bodice of an opera dress. In the middle, Iz right arm reaches into the image and is holding a Quest Virtual Reality Controller. On the right, the dress from the left is shown in Virtual Reality.

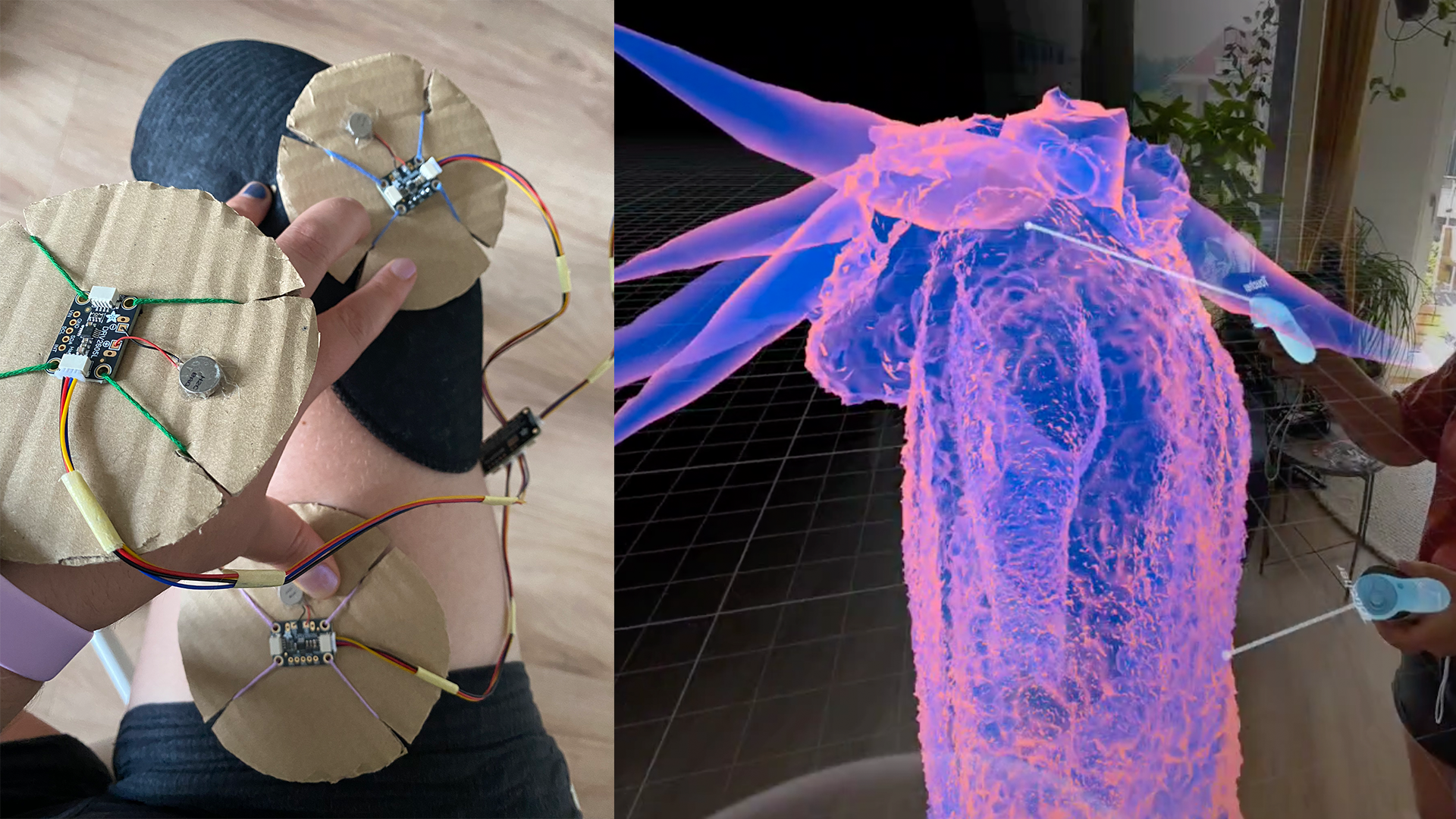

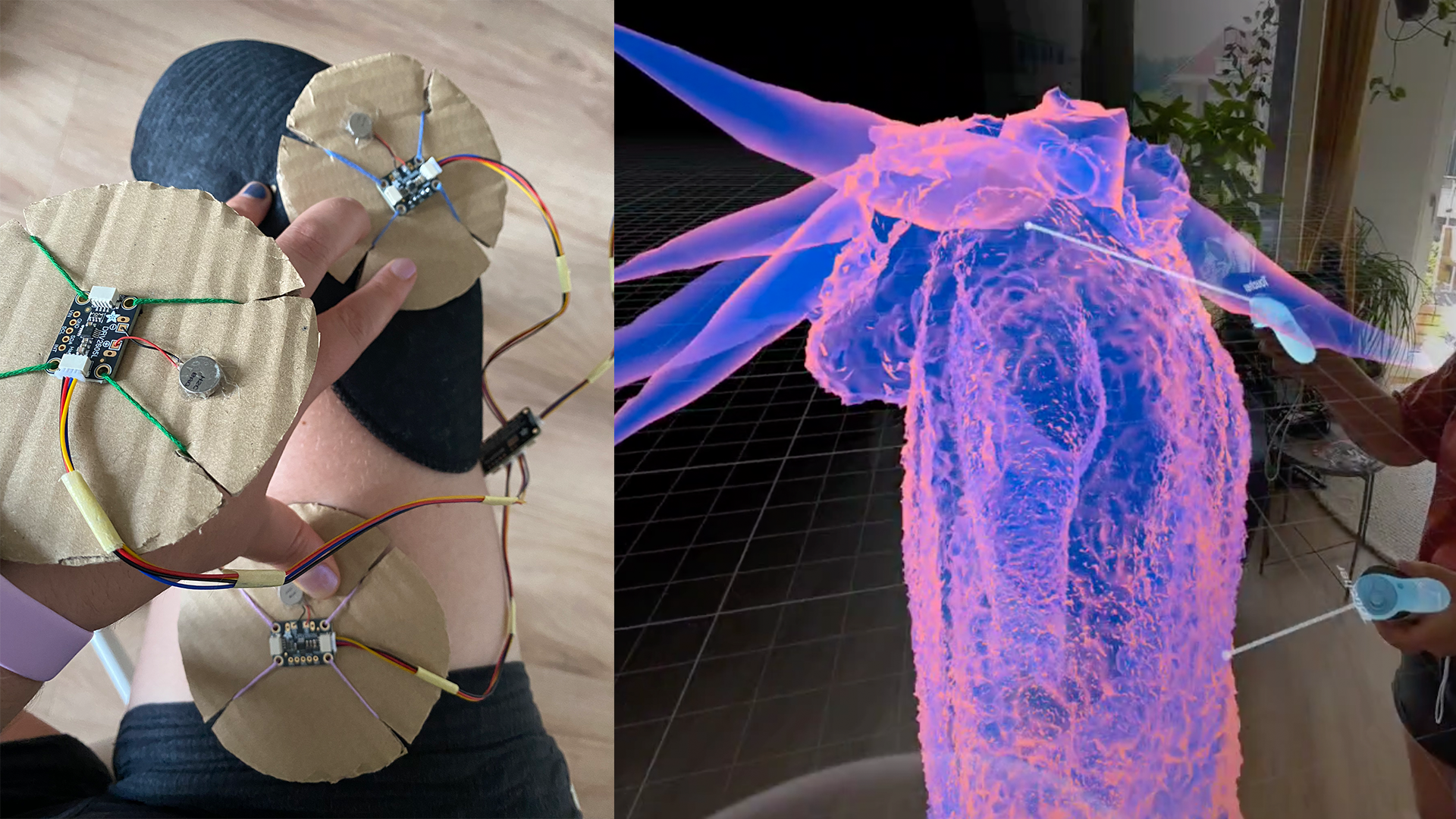

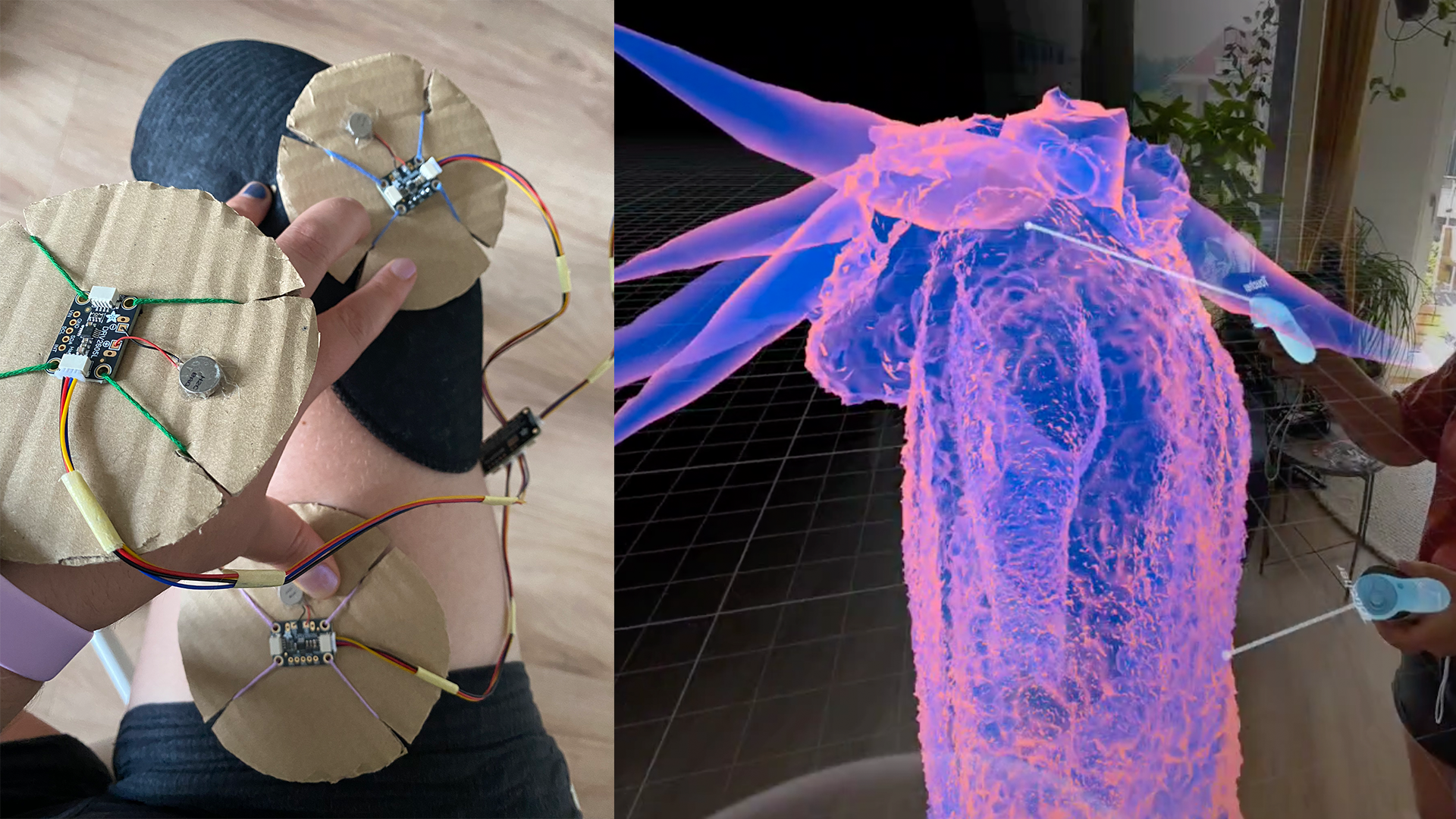

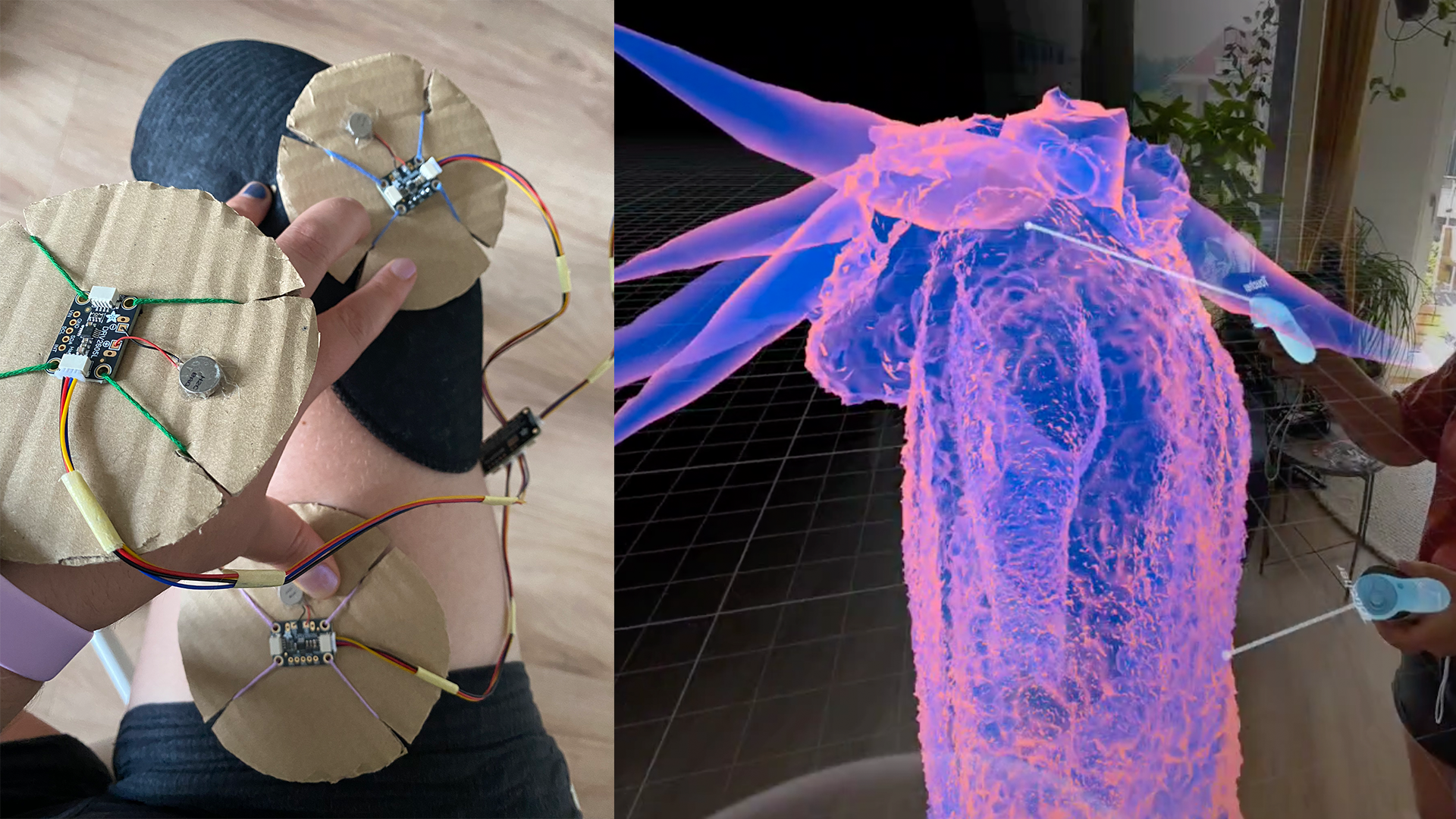

IzPaehr_Collage02: This collage shows how the project experiments with Virtual Reality. On the left, a photo shows a custom controller that Iz is building with two of their hands holding vibration motors attached to cardboard pieces in place. On the right, a screenshot shows the costume of a tiger from the opera The Magic Flute in Virtual Reality. Half of the screenshot shows the virtual space, the other half blends into Iz living room and shows their arms holding Quest controllers.

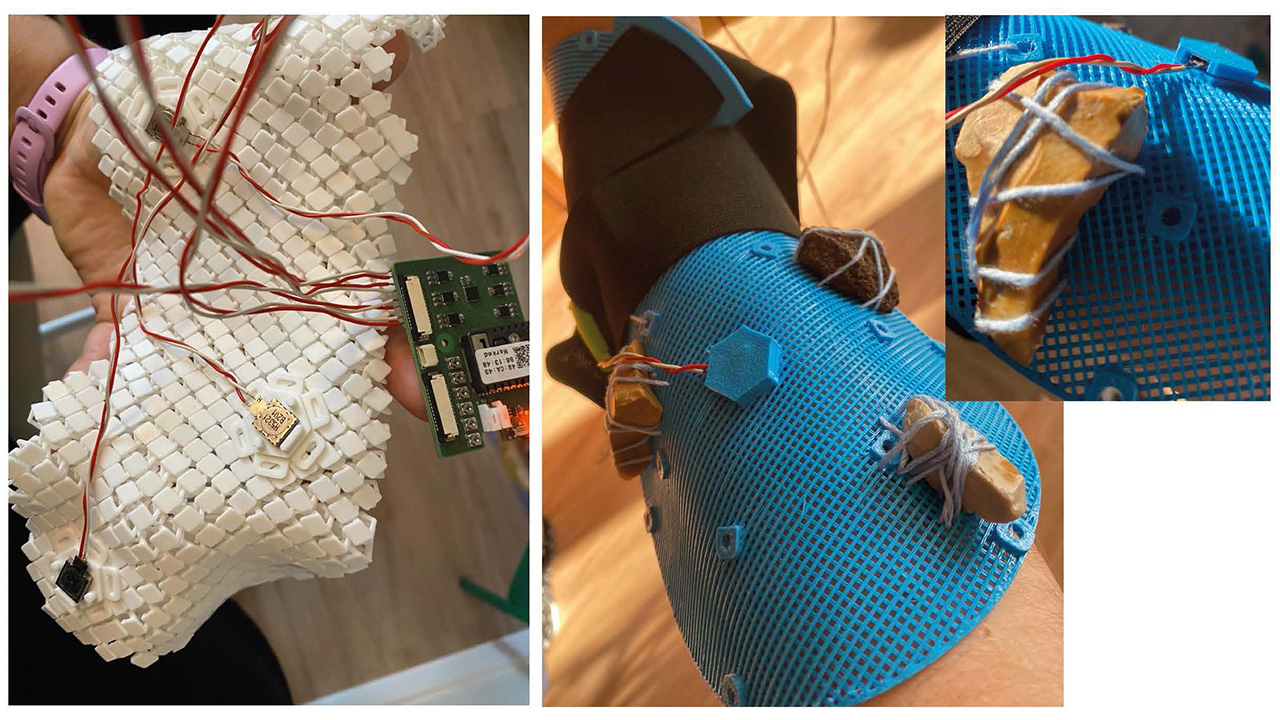

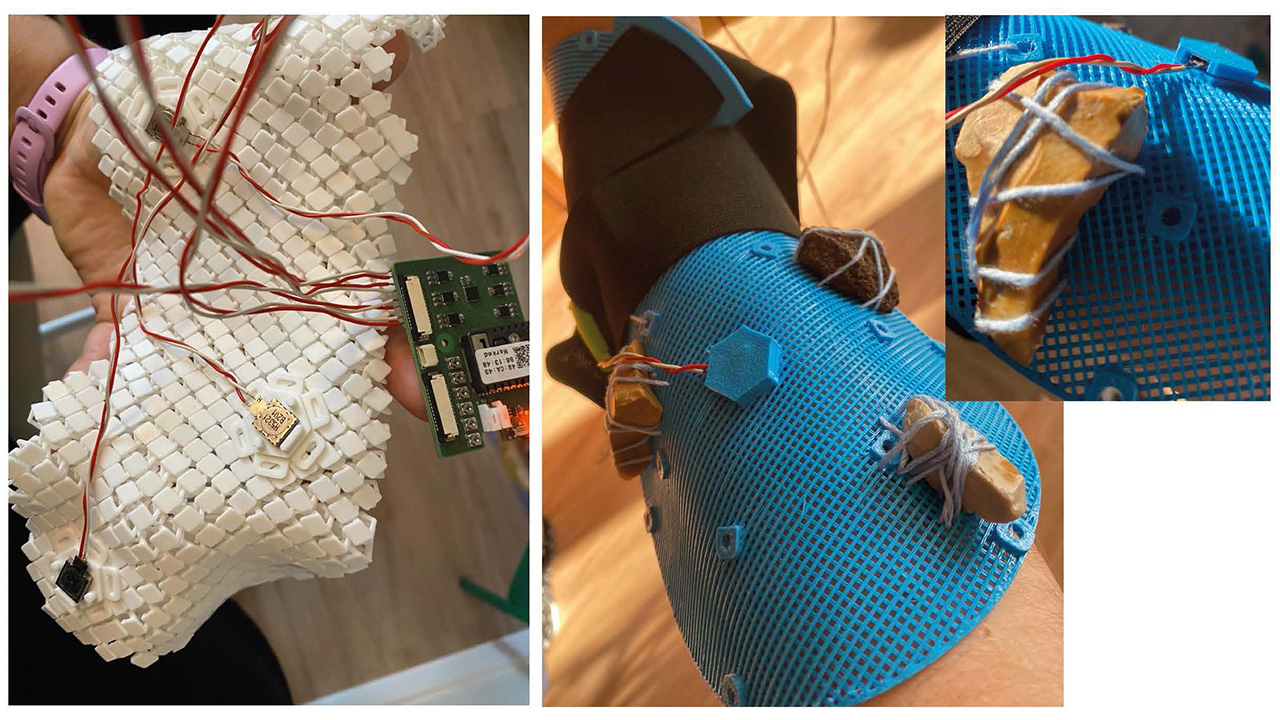

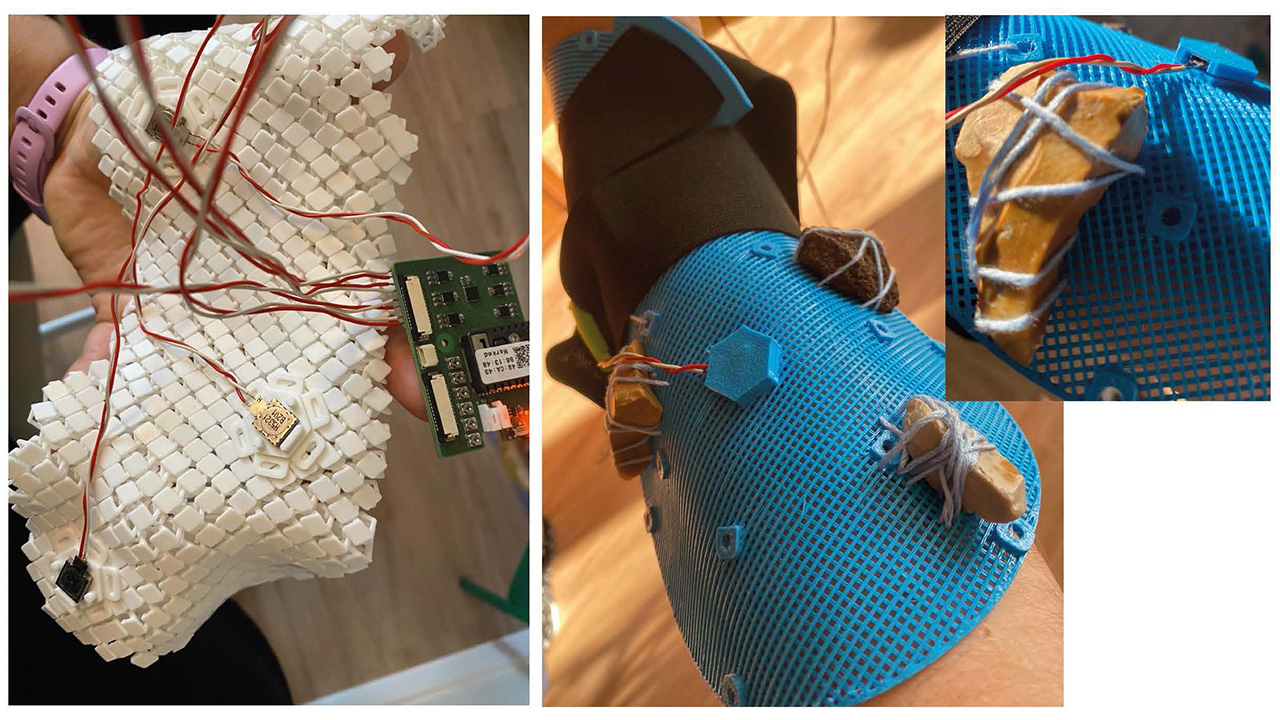

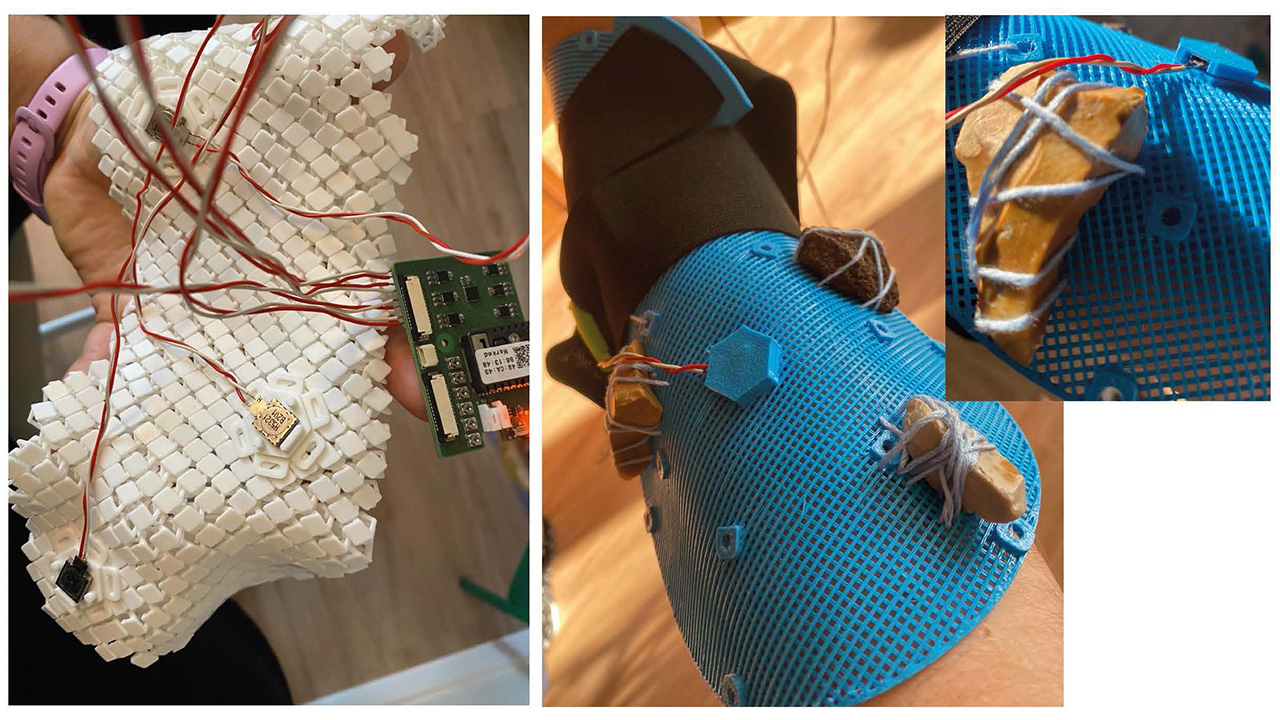

IzPaehr_TactilePatches: A collage shows photos of prototypes of Iz’ alternative controllers. On the left photo, they are holding a controller made from 3D printed fabric into the camera, from which cables and a printed circuit board stick out. On the right, two photos show a soft controller worn on an arm. This controller is a soft 3D printed grid onto which stones are sewn.

ArchiveOfTouch_01: A collage shows the five opera costumes and props that can be felt in the Extended Reality installation Archive of Touch in different colors. In the front, there is an opulent opera dress from the opera Der Rosenkavalier, with two costumes behind it: A tiger, and Papageno from the opera Die Zauberflöte. A bicycle is visible in the back, as well as the costume of one of the ladies from Die Zauberflöte.

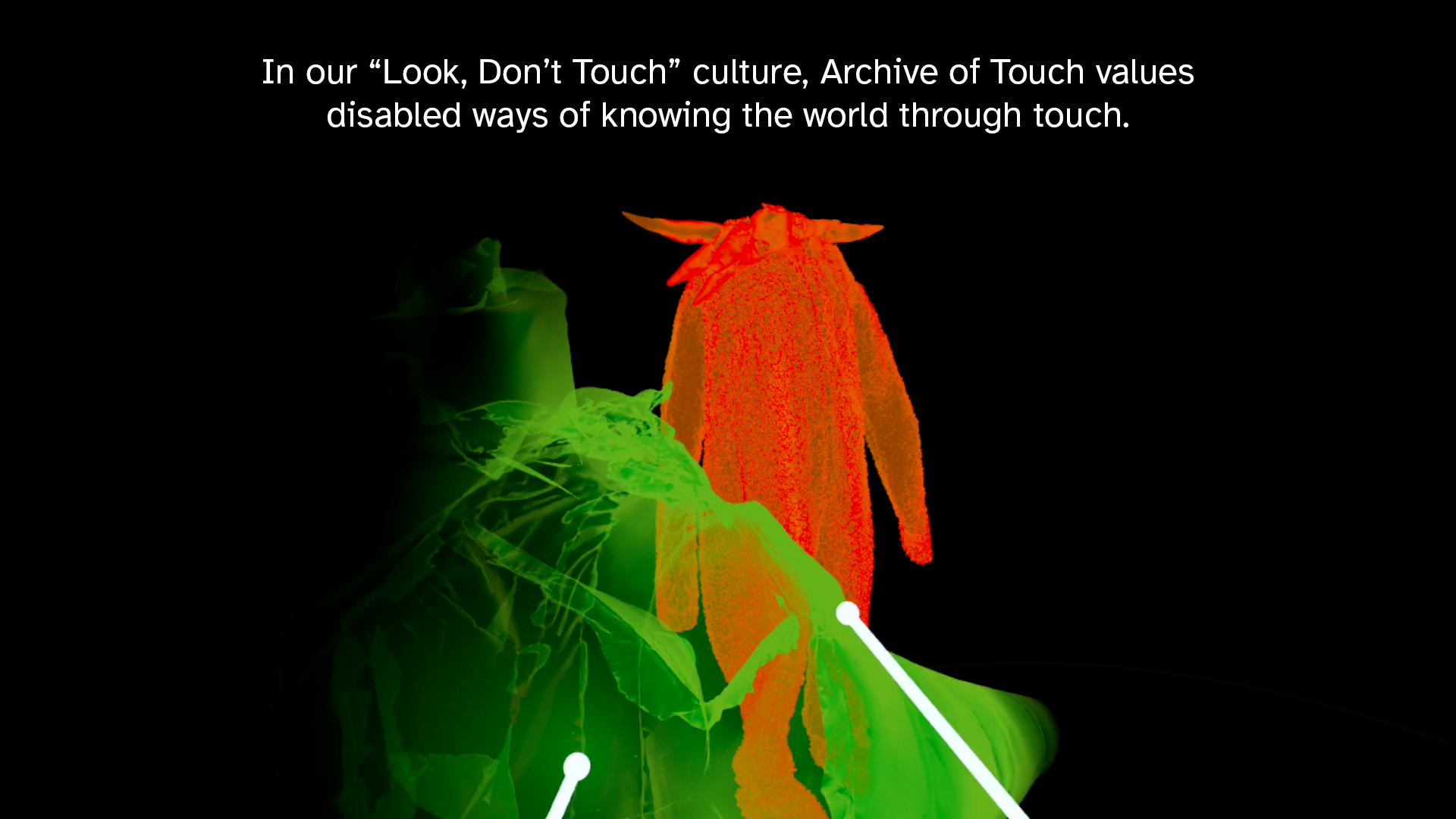

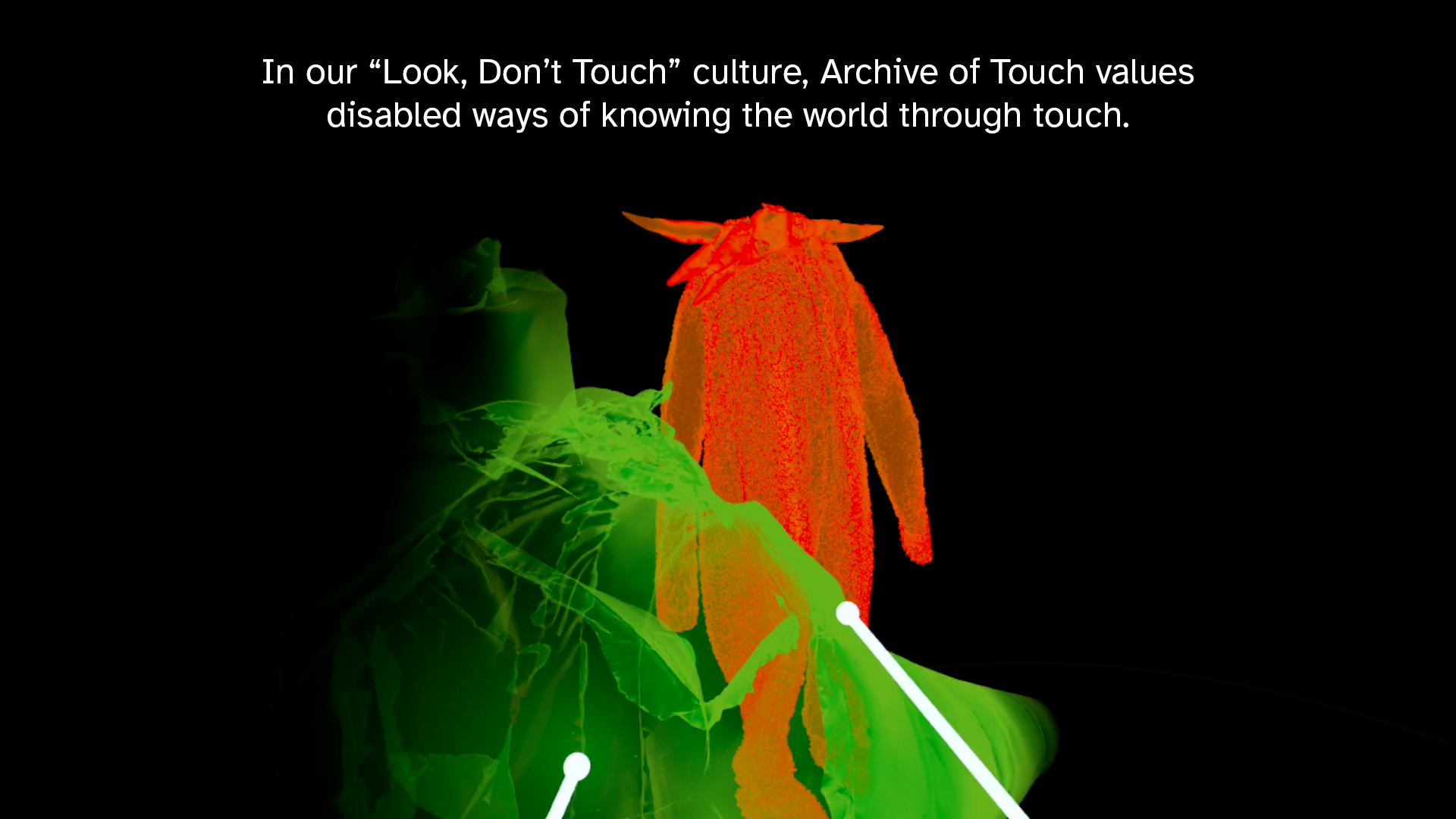

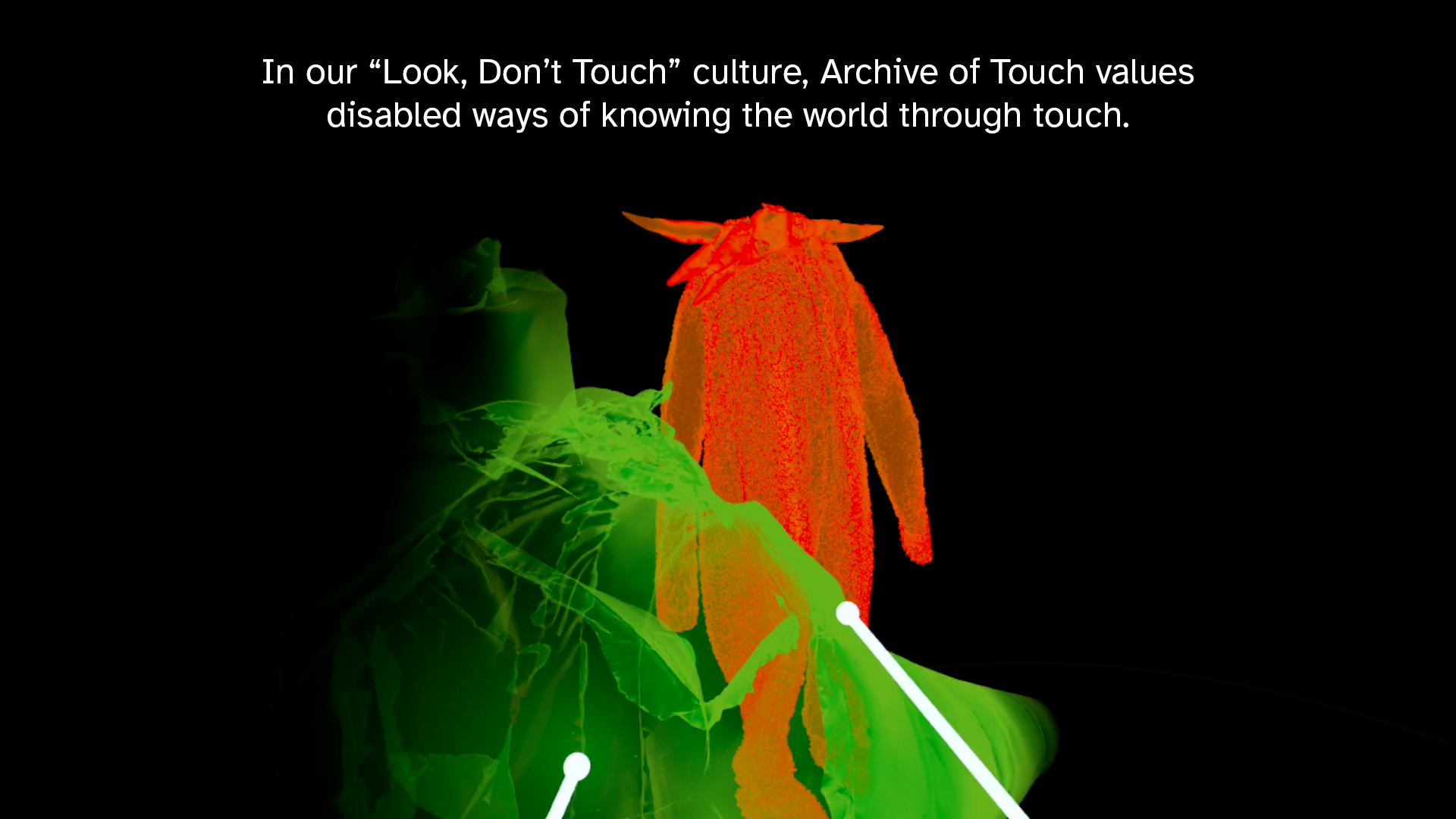

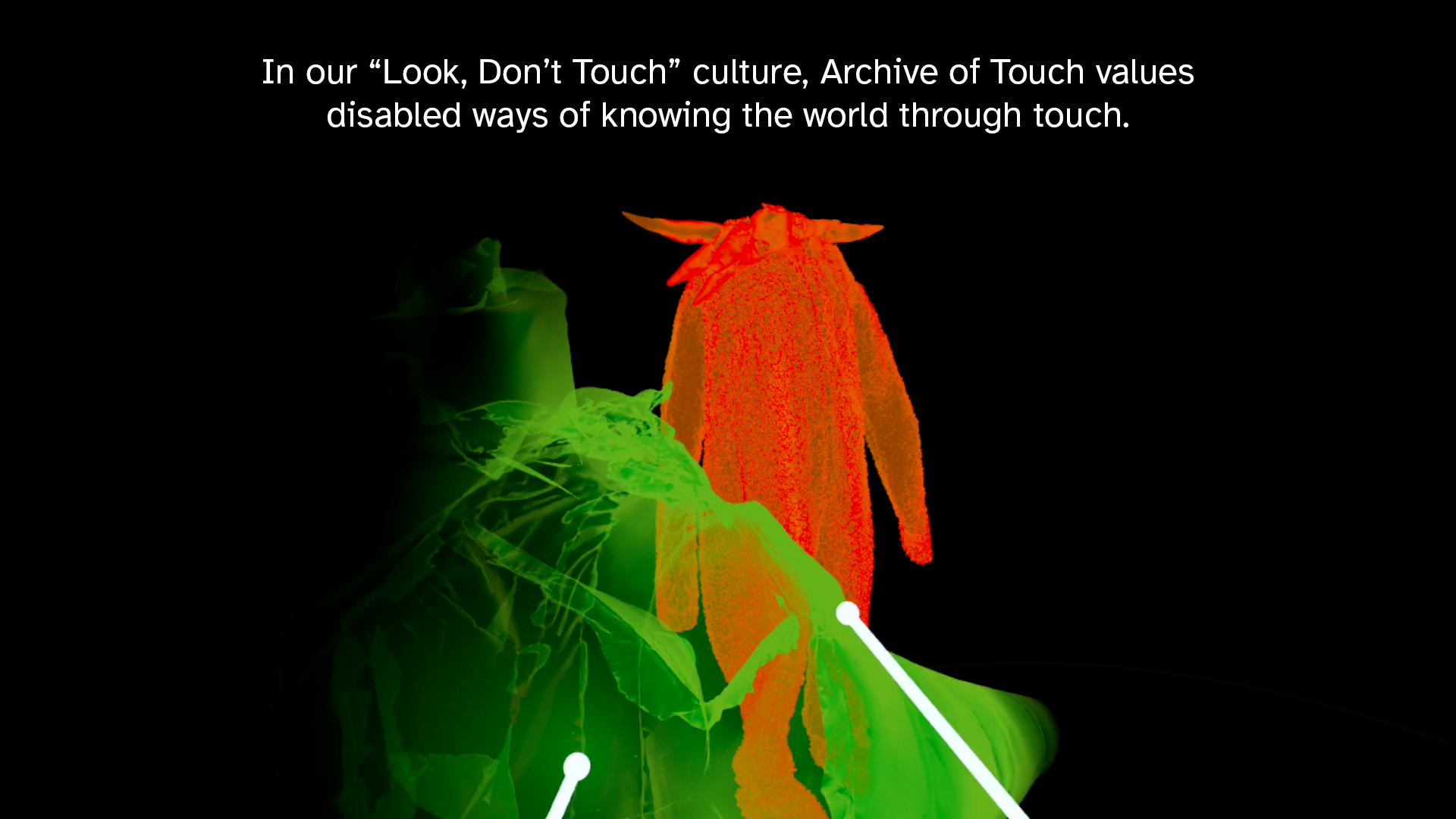

ArchiveOfTouch_02: Two costumes, one of the Magic Flute’s lady, and one of the Magic Flute’s tiger, look like ghostly presences on this screenshot from the Extended Reality artwork Archive of Touch. A text reads: In our „Look, Don’t Touch“ culture, Archive of Touch values disabled ways of knowing the world through touch.

ArchiveOfTouch_03: This collage shows three photos of Iz touching the original dress of the field marshall from the Salzburg Festival 1960ies edition of Der Rosenkavalier. On the left photo, Iz’ hand touches the bodice of the costume. The photo in the middle shows Iz lying on the floor and touching the trim of the costume with their face. The right photo shows fingers tracing the lace on the costume’s elbow.

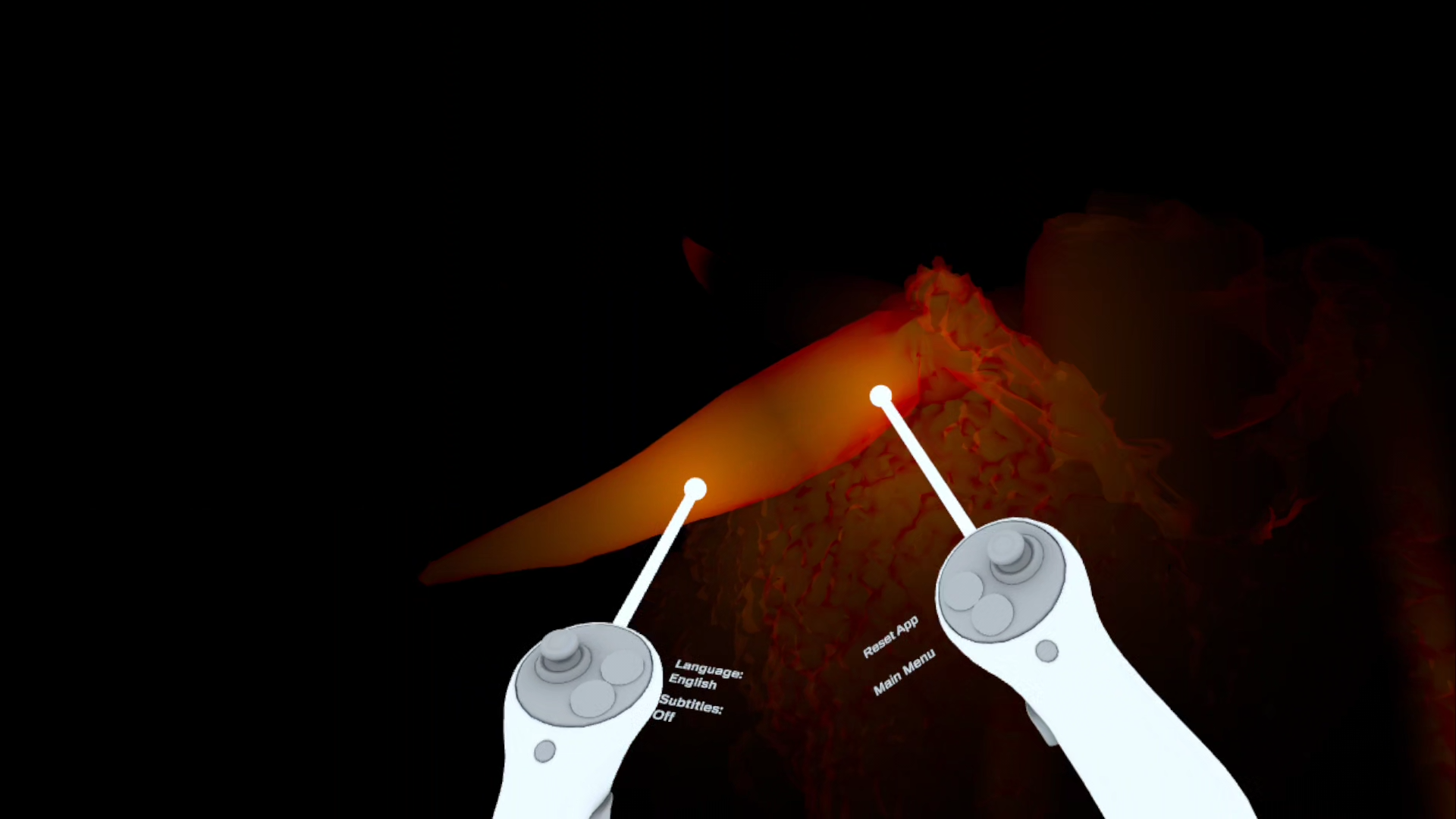

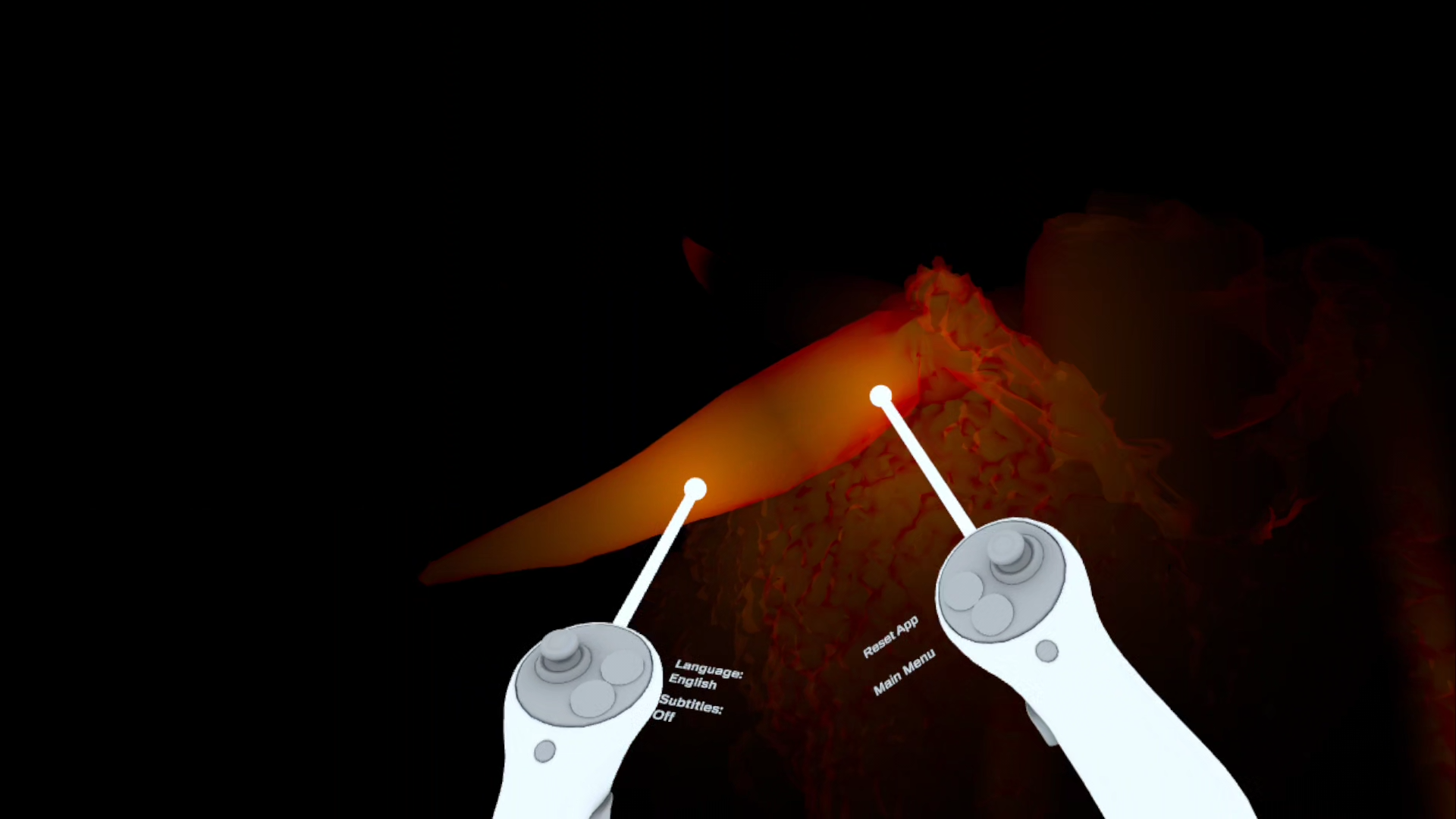

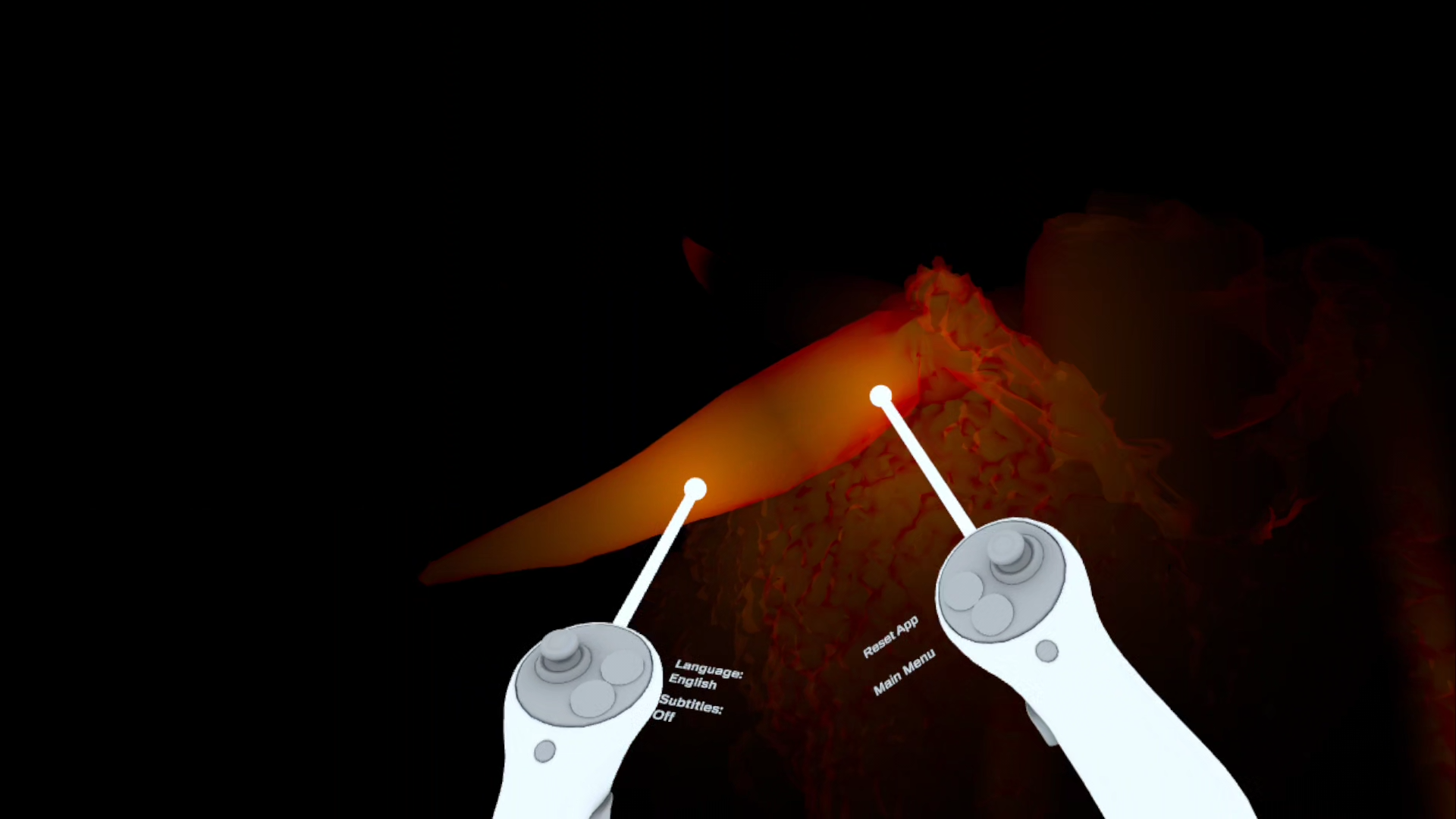

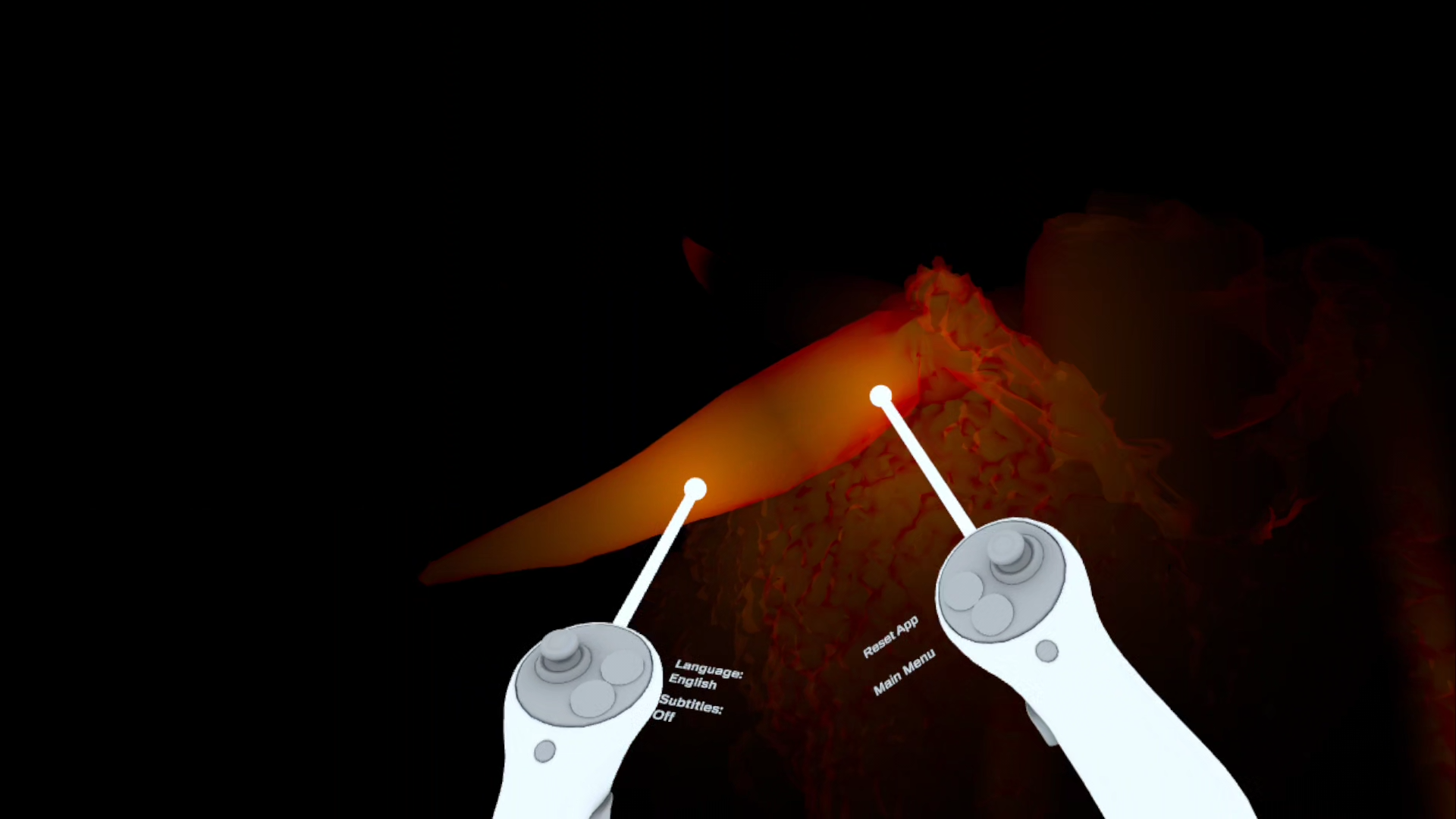

ArchiveOfTouch_04: In this screenshot from the Extended Reality artwork Archive of Touch, two controllers of the Quest3 touch a horn that is part of the costume The Tiger. This costume originates from the opera The Magic Flute that was performed at the stage of Salzburg Festival in 1997. If you held the controllers in your hands, you would feel them vibrate while tracing the virtual costume.

JF - Feeling Virtual begins from lived practices of navigating an inaccessible world rather than retrofitting existing VR systems. How did starting from access reshape what virtual reality could become?

IP - My misfit experiences with VR started with the existing design of the controllers of commercially available VR systems, which are hand-held. Holding a walking stick at the same time makes it laborious to use two controllers at once. Here, my first access hack came in the form of a strap that I wrap around my shoulders and with which I can let the controllers dangle, while also moving with my mobility aid. aStarting from access meant asking questions to other disabled folks, slowing down and testing alternative setups together. I learned from my conversation partners that tactile knowledge is underappreciated in society as well as in technology design. This is why the project moved towards tactile access.

JF -Touch is usually removed from archival encounters in the name of preservation. What happened when you reintroduced touch as a way of knowing the Salzburg Festival Archive?

IP - I continue to be grateful that the team of the Salzburg Festival Archive facilitated my tactile access to their collections without hesitation. In the process of touching my way through opera and theatre history, I learned that sight is quite limited when it comes to knowing archival materials in detail. Often, touching a dress from the costume storage would reveal a hidden knot of embroidery yarn hidden underneath a corsage, or would make apparent that a diamond was made from plastic. I also realized how limited my own language was when trying to put these tactile experiences into words, an experience that resonates with the writings of blind scholars such as Lilian Korner. This is why one outcome of my project is a Tactile Descriptions Workbook that offers guiding questions and tactile sensing exercises to feel out tactile language. Your question on preservation as a reason that materials are kept out of touch is spot on and also concerns archival digitization practices. Many contemporary 3D scanning techniques used by archives follow visual paradigms by scanning outlines of costumes for visual digital representations. My hope is that future preservation does not rely on visual preservation alone, so that we do not lose the rich haptic histories that artifacts can teach us about.

JF - By foregrounding vibration, temperature, resistance, and movement, the project shifts VR away from visual dominance. What kinds of new attentions or intimacies emerged through this multisensorial approach?

IP - During my residency, I took part in a seminar of DeafBlind poet John Lee Clark, who taught me that the goal is not to replace an existing sensory hierarchy with another, but to undo the idea of a hierarchy. Undoing visual dominance meant inviting sensory plurality. In the XR artwork Archive of Touch, the interplay of movement, vibration, resistance and sound creates an intimate experience of being in touch with archival objects. Touch is always relational: You cannot touch without also being touched. In Archive of Touch, every touch creates: sounds, vibrations, descriptions, visual textures. The archival materials from the Salzburg Festival Archive become alive – through our willingness and openness to be in touch with them.

JF - You describe play as fragile, tense, and prone to breakdown. How did failure, slowness, or malfunction become generative forces in the work?

IP - Imagine me in my studio, with vibration motors taped to my knees, fixing bugs on my computer and wishing for the sensations on my skin to finally feel like the silk of an opera dress! I love this question, as it reminds me of the frustrations of slowly and not always successfully working against the technical status quo of VR, as well as the joy of imagining and building controllers that work for many bodies and minds. In a way, this project started out with a failure: Of how commercial VR tech is failing disabled people. And this failure became generative. As the project continued, my prototypes of what a VR experience could feel like failed my disabled test players and me less, but it certainly failed at being what ‘smooth, well working tech’ is imagined as. I keep being very interested in moments of slowness, failure and play when it comes to access making with technology.

JF - Looking ahead, how might starting from crip knowledge and tactile imaginaries transform not just VR, but how we relate to cultural heritage more broadly?

IP - Starting from disabled tactile and remote access knowledges can transform how we think of and use technologies, and how these technologies can facilitate access to cultural heritage. When thinking of remote access, the brilliant work of disabled people at the height of the COVID pandemic comes to mind in sharing knowledges on how to connect online. This work has become part of cultural heritage itself in the form of the Critical Design Lab’s Remote Access Archive. DeafBlind communities use the term Virtual Touch to refer to the ways in which they stay in touch via email listservs. It is time to bring these knowledges in touch with how cultural heritage is commonly preserved and made (in)accessible. I think crip creativity can be a key to overcoming the oftentimes voiced concern that cultural heritage materials cannot be touched by a lot of people without being damaged. Disabled culture teaches us that there are many ways to touch and be in touch with each other and with cultural heritage, that we can hold vulnerability of people and materials together, and that after all, tactile access is something we can invent together, with and without tech.

Image Descriptions:

IzPaehr_Collage01: This collage shows touches across modalities: On the left, Iz hand is shown touching the opulent bodice of an opera dress. In the middle, Iz right arm reaches into the image and is holding a Quest Virtual Reality Controller. On the right, the dress from the left is shown in Virtual Reality.

IzPaehr_Collage02: This collage shows how the project experiments with Virtual Reality. On the left, a photo shows a custom controller that Iz is building with two of their hands holding vibration motors attached to cardboard pieces in place. On the right, a screenshot shows the costume of a tiger from the opera The Magic Flute in Virtual Reality. Half of the screenshot shows the virtual space, the other half blends into Iz living room and shows their arms holding Quest controllers.

IzPaehr_TactilePatches: A collage shows photos of prototypes of Iz’ alternative controllers. On the left photo, they are holding a controller made from 3D printed fabric into the camera, from which cables and a printed circuit board stick out. On the right, two photos show a soft controller worn on an arm. This controller is a soft 3D printed grid onto which stones are sewn.

ArchiveOfTouch_01: A collage shows the five opera costumes and props that can be felt in the Extended Reality installation Archive of Touch in different colors. In the front, there is an opulent opera dress from the opera Der Rosenkavalier, with two costumes behind it: A tiger, and Papageno from the opera Die Zauberflöte. A bicycle is visible in the back, as well as the costume of one of the ladies from Die Zauberflöte.

ArchiveOfTouch_02: Two costumes, one of the Magic Flute’s lady, and one of the Magic Flute’s tiger, look like ghostly presences on this screenshot from the Extended Reality artwork Archive of Touch. A text reads: In our „Look, Don’t Touch“ culture, Archive of Touch values disabled ways of knowing the world through touch.

ArchiveOfTouch_03: This collage shows three photos of Iz touching the original dress of the field marshall from the Salzburg Festival 1960ies edition of Der Rosenkavalier. On the left photo, Iz’ hand touches the bodice of the costume. The photo in the middle shows Iz lying on the floor and touching the trim of the costume with their face. The right photo shows fingers tracing the lace on the costume’s elbow.

ArchiveOfTouch_04: In this screenshot from the Extended Reality artwork Archive of Touch, two controllers of the Quest3 touch a horn that is part of the costume The Tiger. This costume originates from the opera The Magic Flute that was performed at the stage of Salzburg Festival in 1997. If you held the controllers in your hands, you would feel them vibrate while tracing the virtual costume.

Iz Paehr is an iterdisciplinary designer in love with disability access, internet infrastructure, and the subversive potential of play.

INTERVIEW WITH IZ PAEHR

JF - Feeling Virtual begins from lived practices of navigating an inaccessible world rather than retrofitting existing VR systems. How did starting from access reshape what virtual reality could become?

IP - My misfit experiences with VR started with the existing design of the controllers of commercially available VR systems, which are hand-held. Holding a walking stick at the same time makes it laborious to use two controllers at once. Here, my first access hack came in the form of a strap that I wrap around my shoulders and with which I can let the controllers dangle, while also moving with my mobility aid. aStarting from access meant asking questions to other disabled folks, slowing down and testing alternative setups together. I learned from my conversation partners that tactile knowledge is underappreciated in society as well as in technology design. This is why the project moved towards tactile access.

JF -Touch is usually removed from archival encounters in the name of preservation. What happened when you reintroduced touch as a way of knowing the Salzburg Festival Archive?

IP - I continue to be grateful that the team of the Salzburg Festival Archive facilitated my tactile access to their collections without hesitation. In the process of touching my way through opera and theatre history, I learned that sight is quite limited when it comes to knowing archival materials in detail. Often, touching a dress from the costume storage would reveal a hidden knot of embroidery yarn hidden underneath a corsage, or would make apparent that a diamond was made from plastic. I also realized how limited my own language was when trying to put these tactile experiences into words, an experience that resonates with the writings of blind scholars such as Lilian Korner. This is why one outcome of my project is a Tactile Descriptions Workbook that offers guiding questions and tactile sensing exercises to feel out tactile language. Your question on preservation as a reason that materials are kept out of touch is spot on and also concerns archival digitization practices. Many contemporary 3D scanning techniques used by archives follow visual paradigms by scanning outlines of costumes for visual digital representations. My hope is that future preservation does not rely on visual preservation alone, so that we do not lose the rich haptic histories that artifacts can teach us about.

JF - By foregrounding vibration, temperature, resistance, and movement, the project shifts VR away from visual dominance. What kinds of new attentions or intimacies emerged through this multisensorial approach?

IP - During my residency, I took part in a seminar of DeafBlind poet John Lee Clark, who taught me that the goal is not to replace an existing sensory hierarchy with another, but to undo the idea of a hierarchy. Undoing visual dominance meant inviting sensory plurality. In the XR artwork Archive of Touch, the interplay of movement, vibration, resistance and sound creates an intimate experience of being in touch with archival objects. Touch is always relational: You cannot touch without also being touched. In Archive of Touch, every touch creates: sounds, vibrations, descriptions, visual textures. The archival materials from the Salzburg Festival Archive become alive – through our willingness and openness to be in touch with them.

JF - You describe play as fragile, tense, and prone to breakdown. How did failure, slowness, or malfunction become generative forces in the work?

IP - Imagine me in my studio, with vibration motors taped to my knees, fixing bugs on my computer and wishing for the sensations on my skin to finally feel like the silk of an opera dress! I love this question, as it reminds me of the frustrations of slowly and not always successfully working against the technical status quo of VR, as well as the joy of imagining and building controllers that work for many bodies and minds. In a way, this project started out with a failure: Of how commercial VR tech is failing disabled people. And this failure became generative. As the project continued, my prototypes of what a VR experience could feel like failed my disabled test players and me less, but it certainly failed at being what ‘smooth, well working tech’ is imagined as. I keep being very interested in moments of slowness, failure and play when it comes to access making with technology.

JF - Looking ahead, how might starting from crip knowledge and tactile imaginaries transform not just VR, but how we relate to cultural heritage more broadly?

IP - Starting from disabled tactile and remote access knowledges can transform how we think of and use technologies, and how these technologies can facilitate access to cultural heritage. When thinking of remote access, the brilliant work of disabled people at the height of the COVID pandemic comes to mind in sharing knowledges on how to connect online. This work has become part of cultural heritage itself in the form of the Critical Design Lab’s Remote Access Archive. DeafBlind communities use the term Virtual Touch to refer to the ways in which they stay in touch via email listservs. It is time to bring these knowledges in touch with how cultural heritage is commonly preserved and made (in)accessible. I think crip creativity can be a key to overcoming the oftentimes voiced concern that cultural heritage materials cannot be touched by a lot of people without being damaged. Disabled culture teaches us that there are many ways to touch and be in touch with each other and with cultural heritage, that we can hold vulnerability of people and materials together, and that after all, tactile access is something we can invent together, with and without tech.

Image Descriptions:

IzPaehr_Collage01: This collage shows touches across modalities: On the left, Iz hand is shown touching the opulent bodice of an opera dress. In the middle, Iz right arm reaches into the image and is holding a Quest Virtual Reality Controller. On the right, the dress from the left is shown in Virtual Reality.

IzPaehr_Collage02: This collage shows how the project experiments with Virtual Reality. On the left, a photo shows a custom controller that Iz is building with two of their hands holding vibration motors attached to cardboard pieces in place. On the right, a screenshot shows the costume of a tiger from the opera The Magic Flute in Virtual Reality. Half of the screenshot shows the virtual space, the other half blends into Iz living room and shows their arms holding Quest controllers.

IzPaehr_TactilePatches: A collage shows photos of prototypes of Iz’ alternative controllers. On the left photo, they are holding a controller made from 3D printed fabric into the camera, from which cables and a printed circuit board stick out. On the right, two photos show a soft controller worn on an arm. This controller is a soft 3D printed grid onto which stones are sewn.

ArchiveOfTouch_01: A collage shows the five opera costumes and props that can be felt in the Extended Reality installation Archive of Touch in different colors. In the front, there is an opulent opera dress from the opera Der Rosenkavalier, with two costumes behind it: A tiger, and Papageno from the opera Die Zauberflöte. A bicycle is visible in the back, as well as the costume of one of the ladies from Die Zauberflöte.

ArchiveOfTouch_02: Two costumes, one of the Magic Flute’s lady, and one of the Magic Flute’s tiger, look like ghostly presences on this screenshot from the Extended Reality artwork Archive of Touch. A text reads: In our „Look, Don’t Touch“ culture, Archive of Touch values disabled ways of knowing the world through touch.

ArchiveOfTouch_03: This collage shows three photos of Iz touching the original dress of the field marshall from the Salzburg Festival 1960ies edition of Der Rosenkavalier. On the left photo, Iz’ hand touches the bodice of the costume. The photo in the middle shows Iz lying on the floor and touching the trim of the costume with their face. The right photo shows fingers tracing the lace on the costume’s elbow.

ArchiveOfTouch_04: In this screenshot from the Extended Reality artwork Archive of Touch, two controllers of the Quest3 touch a horn that is part of the costume The Tiger. This costume originates from the opera The Magic Flute that was performed at the stage of Salzburg Festival in 1997. If you held the controllers in your hands, you would feel them vibrate while tracing the virtual costume.

JF - Feeling Virtual begins from lived practices of navigating an inaccessible world rather than retrofitting existing VR systems. How did starting from access reshape what virtual reality could become?

IP - My misfit experiences with VR started with the existing design of the controllers of commercially available VR systems, which are hand-held. Holding a walking stick at the same time makes it laborious to use two controllers at once. Here, my first access hack came in the form of a strap that I wrap around my shoulders and with which I can let the controllers dangle, while also moving with my mobility aid. aStarting from access meant asking questions to other disabled folks, slowing down and testing alternative setups together. I learned from my conversation partners that tactile knowledge is underappreciated in society as well as in technology design. This is why the project moved towards tactile access.

JF -Touch is usually removed from archival encounters in the name of preservation. What happened when you reintroduced touch as a way of knowing the Salzburg Festival Archive?

IP - I continue to be grateful that the team of the Salzburg Festival Archive facilitated my tactile access to their collections without hesitation. In the process of touching my way through opera and theatre history, I learned that sight is quite limited when it comes to knowing archival materials in detail. Often, touching a dress from the costume storage would reveal a hidden knot of embroidery yarn hidden underneath a corsage, or would make apparent that a diamond was made from plastic. I also realized how limited my own language was when trying to put these tactile experiences into words, an experience that resonates with the writings of blind scholars such as Lilian Korner. This is why one outcome of my project is a Tactile Descriptions Workbook that offers guiding questions and tactile sensing exercises to feel out tactile language. Your question on preservation as a reason that materials are kept out of touch is spot on and also concerns archival digitization practices. Many contemporary 3D scanning techniques used by archives follow visual paradigms by scanning outlines of costumes for visual digital representations. My hope is that future preservation does not rely on visual preservation alone, so that we do not lose the rich haptic histories that artifacts can teach us about.

JF - By foregrounding vibration, temperature, resistance, and movement, the project shifts VR away from visual dominance. What kinds of new attentions or intimacies emerged through this multisensorial approach?

IP - During my residency, I took part in a seminar of DeafBlind poet John Lee Clark, who taught me that the goal is not to replace an existing sensory hierarchy with another, but to undo the idea of a hierarchy. Undoing visual dominance meant inviting sensory plurality. In the XR artwork Archive of Touch, the interplay of movement, vibration, resistance and sound creates an intimate experience of being in touch with archival objects. Touch is always relational: You cannot touch without also being touched. In Archive of Touch, every touch creates: sounds, vibrations, descriptions, visual textures. The archival materials from the Salzburg Festival Archive become alive – through our willingness and openness to be in touch with them.

JF - You describe play as fragile, tense, and prone to breakdown. How did failure, slowness, or malfunction become generative forces in the work?

IP - Imagine me in my studio, with vibration motors taped to my knees, fixing bugs on my computer and wishing for the sensations on my skin to finally feel like the silk of an opera dress! I love this question, as it reminds me of the frustrations of slowly and not always successfully working against the technical status quo of VR, as well as the joy of imagining and building controllers that work for many bodies and minds. In a way, this project started out with a failure: Of how commercial VR tech is failing disabled people. And this failure became generative. As the project continued, my prototypes of what a VR experience could feel like failed my disabled test players and me less, but it certainly failed at being what ‘smooth, well working tech’ is imagined as. I keep being very interested in moments of slowness, failure and play when it comes to access making with technology.

JF - Looking ahead, how might starting from crip knowledge and tactile imaginaries transform not just VR, but how we relate to cultural heritage more broadly?

IP - Starting from disabled tactile and remote access knowledges can transform how we think of and use technologies, and how these technologies can facilitate access to cultural heritage. When thinking of remote access, the brilliant work of disabled people at the height of the COVID pandemic comes to mind in sharing knowledges on how to connect online. This work has become part of cultural heritage itself in the form of the Critical Design Lab’s Remote Access Archive. DeafBlind communities use the term Virtual Touch to refer to the ways in which they stay in touch via email listservs. It is time to bring these knowledges in touch with how cultural heritage is commonly preserved and made (in)accessible. I think crip creativity can be a key to overcoming the oftentimes voiced concern that cultural heritage materials cannot be touched by a lot of people without being damaged. Disabled culture teaches us that there are many ways to touch and be in touch with each other and with cultural heritage, that we can hold vulnerability of people and materials together, and that after all, tactile access is something we can invent together, with and without tech.

Image Descriptions:

IzPaehr_Collage01: This collage shows touches across modalities: On the left, Iz hand is shown touching the opulent bodice of an opera dress. In the middle, Iz right arm reaches into the image and is holding a Quest Virtual Reality Controller. On the right, the dress from the left is shown in Virtual Reality.

IzPaehr_Collage02: This collage shows how the project experiments with Virtual Reality. On the left, a photo shows a custom controller that Iz is building with two of their hands holding vibration motors attached to cardboard pieces in place. On the right, a screenshot shows the costume of a tiger from the opera The Magic Flute in Virtual Reality. Half of the screenshot shows the virtual space, the other half blends into Iz living room and shows their arms holding Quest controllers.

IzPaehr_TactilePatches: A collage shows photos of prototypes of Iz’ alternative controllers. On the left photo, they are holding a controller made from 3D printed fabric into the camera, from which cables and a printed circuit board stick out. On the right, two photos show a soft controller worn on an arm. This controller is a soft 3D printed grid onto which stones are sewn.

ArchiveOfTouch_01: A collage shows the five opera costumes and props that can be felt in the Extended Reality installation Archive of Touch in different colors. In the front, there is an opulent opera dress from the opera Der Rosenkavalier, with two costumes behind it: A tiger, and Papageno from the opera Die Zauberflöte. A bicycle is visible in the back, as well as the costume of one of the ladies from Die Zauberflöte.

ArchiveOfTouch_02: Two costumes, one of the Magic Flute’s lady, and one of the Magic Flute’s tiger, look like ghostly presences on this screenshot from the Extended Reality artwork Archive of Touch. A text reads: In our „Look, Don’t Touch“ culture, Archive of Touch values disabled ways of knowing the world through touch.

ArchiveOfTouch_03: This collage shows three photos of Iz touching the original dress of the field marshall from the Salzburg Festival 1960ies edition of Der Rosenkavalier. On the left photo, Iz’ hand touches the bodice of the costume. The photo in the middle shows Iz lying on the floor and touching the trim of the costume with their face. The right photo shows fingers tracing the lace on the costume’s elbow.

ArchiveOfTouch_04: In this screenshot from the Extended Reality artwork Archive of Touch, two controllers of the Quest3 touch a horn that is part of the costume The Tiger. This costume originates from the opera The Magic Flute that was performed at the stage of Salzburg Festival in 1997. If you held the controllers in your hands, you would feel them vibrate while tracing the virtual costume.

Iz Paehr is an iterdisciplinary designer in love with disability access, internet infrastructure, and the subversive potential of play.

INTERVIEW WITH IZ PAEHR

JF - Feeling Virtual begins from lived practices of navigating an inaccessible world rather than retrofitting existing VR systems. How did starting from access reshape what virtual reality could become?

IP - My misfit experiences with VR started with the existing design of the controllers of commercially available VR systems, which are hand-held. Holding a walking stick at the same time makes it laborious to use two controllers at once. Here, my first access hack came in the form of a strap that I wrap around my shoulders and with which I can let the controllers dangle, while also moving with my mobility aid. aStarting from access meant asking questions to other disabled folks, slowing down and testing alternative setups together. I learned from my conversation partners that tactile knowledge is underappreciated in society as well as in technology design. This is why the project moved towards tactile access.

JF -Touch is usually removed from archival encounters in the name of preservation. What happened when you reintroduced touch as a way of knowing the Salzburg Festival Archive?

IP - I continue to be grateful that the team of the Salzburg Festival Archive facilitated my tactile access to their collections without hesitation. In the process of touching my way through opera and theatre history, I learned that sight is quite limited when it comes to knowing archival materials in detail. Often, touching a dress from the costume storage would reveal a hidden knot of embroidery yarn hidden underneath a corsage, or would make apparent that a diamond was made from plastic. I also realized how limited my own language was when trying to put these tactile experiences into words, an experience that resonates with the writings of blind scholars such as Lilian Korner. This is why one outcome of my project is a Tactile Descriptions Workbook that offers guiding questions and tactile sensing exercises to feel out tactile language. Your question on preservation as a reason that materials are kept out of touch is spot on and also concerns archival digitization practices. Many contemporary 3D scanning techniques used by archives follow visual paradigms by scanning outlines of costumes for visual digital representations. My hope is that future preservation does not rely on visual preservation alone, so that we do not lose the rich haptic histories that artifacts can teach us about.

JF - By foregrounding vibration, temperature, resistance, and movement, the project shifts VR away from visual dominance. What kinds of new attentions or intimacies emerged through this multisensorial approach?

IP - During my residency, I took part in a seminar of DeafBlind poet John Lee Clark, who taught me that the goal is not to replace an existing sensory hierarchy with another, but to undo the idea of a hierarchy. Undoing visual dominance meant inviting sensory plurality. In the XR artwork Archive of Touch, the interplay of movement, vibration, resistance and sound creates an intimate experience of being in touch with archival objects. Touch is always relational: You cannot touch without also being touched. In Archive of Touch, every touch creates: sounds, vibrations, descriptions, visual textures. The archival materials from the Salzburg Festival Archive become alive – through our willingness and openness to be in touch with them.

JF - You describe play as fragile, tense, and prone to breakdown. How did failure, slowness, or malfunction become generative forces in the work?

IP - Imagine me in my studio, with vibration motors taped to my knees, fixing bugs on my computer and wishing for the sensations on my skin to finally feel like the silk of an opera dress! I love this question, as it reminds me of the frustrations of slowly and not always successfully working against the technical status quo of VR, as well as the joy of imagining and building controllers that work for many bodies and minds. In a way, this project started out with a failure: Of how commercial VR tech is failing disabled people. And this failure became generative. As the project continued, my prototypes of what a VR experience could feel like failed my disabled test players and me less, but it certainly failed at being what ‘smooth, well working tech’ is imagined as. I keep being very interested in moments of slowness, failure and play when it comes to access making with technology.

JF - Looking ahead, how might starting from crip knowledge and tactile imaginaries transform not just VR, but how we relate to cultural heritage more broadly?

IP - Starting from disabled tactile and remote access knowledges can transform how we think of and use technologies, and how these technologies can facilitate access to cultural heritage. When thinking of remote access, the brilliant work of disabled people at the height of the COVID pandemic comes to mind in sharing knowledges on how to connect online. This work has become part of cultural heritage itself in the form of the Critical Design Lab’s Remote Access Archive. DeafBlind communities use the term Virtual Touch to refer to the ways in which they stay in touch via email listservs. It is time to bring these knowledges in touch with how cultural heritage is commonly preserved and made (in)accessible. I think crip creativity can be a key to overcoming the oftentimes voiced concern that cultural heritage materials cannot be touched by a lot of people without being damaged. Disabled culture teaches us that there are many ways to touch and be in touch with each other and with cultural heritage, that we can hold vulnerability of people and materials together, and that after all, tactile access is something we can invent together, with and without tech.

Image Descriptions:

IzPaehr_Collage01: This collage shows touches across modalities: On the left, Iz hand is shown touching the opulent bodice of an opera dress. In the middle, Iz right arm reaches into the image and is holding a Quest Virtual Reality Controller. On the right, the dress from the left is shown in Virtual Reality.

IzPaehr_Collage02: This collage shows how the project experiments with Virtual Reality. On the left, a photo shows a custom controller that Iz is building with two of their hands holding vibration motors attached to cardboard pieces in place. On the right, a screenshot shows the costume of a tiger from the opera The Magic Flute in Virtual Reality. Half of the screenshot shows the virtual space, the other half blends into Iz living room and shows their arms holding Quest controllers.

IzPaehr_TactilePatches: A collage shows photos of prototypes of Iz’ alternative controllers. On the left photo, they are holding a controller made from 3D printed fabric into the camera, from which cables and a printed circuit board stick out. On the right, two photos show a soft controller worn on an arm. This controller is a soft 3D printed grid onto which stones are sewn.

ArchiveOfTouch_01: A collage shows the five opera costumes and props that can be felt in the Extended Reality installation Archive of Touch in different colors. In the front, there is an opulent opera dress from the opera Der Rosenkavalier, with two costumes behind it: A tiger, and Papageno from the opera Die Zauberflöte. A bicycle is visible in the back, as well as the costume of one of the ladies from Die Zauberflöte.

ArchiveOfTouch_02: Two costumes, one of the Magic Flute’s lady, and one of the Magic Flute’s tiger, look like ghostly presences on this screenshot from the Extended Reality artwork Archive of Touch. A text reads: In our „Look, Don’t Touch“ culture, Archive of Touch values disabled ways of knowing the world through touch.

ArchiveOfTouch_03: This collage shows three photos of Iz touching the original dress of the field marshall from the Salzburg Festival 1960ies edition of Der Rosenkavalier. On the left photo, Iz’ hand touches the bodice of the costume. The photo in the middle shows Iz lying on the floor and touching the trim of the costume with their face. The right photo shows fingers tracing the lace on the costume’s elbow.

ArchiveOfTouch_04: In this screenshot from the Extended Reality artwork Archive of Touch, two controllers of the Quest3 touch a horn that is part of the costume The Tiger. This costume originates from the opera The Magic Flute that was performed at the stage of Salzburg Festival in 1997. If you held the controllers in your hands, you would feel them vibrate while tracing the virtual costume.

JF - Feeling Virtual begins from lived practices of navigating an inaccessible world rather than retrofitting existing VR systems. How did starting from access reshape what virtual reality could become?

IP - My misfit experiences with VR started with the existing design of the controllers of commercially available VR systems, which are hand-held. Holding a walking stick at the same time makes it laborious to use two controllers at once. Here, my first access hack came in the form of a strap that I wrap around my shoulders and with which I can let the controllers dangle, while also moving with my mobility aid. aStarting from access meant asking questions to other disabled folks, slowing down and testing alternative setups together. I learned from my conversation partners that tactile knowledge is underappreciated in society as well as in technology design. This is why the project moved towards tactile access.

JF -Touch is usually removed from archival encounters in the name of preservation. What happened when you reintroduced touch as a way of knowing the Salzburg Festival Archive?

IP - I continue to be grateful that the team of the Salzburg Festival Archive facilitated my tactile access to their collections without hesitation. In the process of touching my way through opera and theatre history, I learned that sight is quite limited when it comes to knowing archival materials in detail. Often, touching a dress from the costume storage would reveal a hidden knot of embroidery yarn hidden underneath a corsage, or would make apparent that a diamond was made from plastic. I also realized how limited my own language was when trying to put these tactile experiences into words, an experience that resonates with the writings of blind scholars such as Lilian Korner. This is why one outcome of my project is a Tactile Descriptions Workbook that offers guiding questions and tactile sensing exercises to feel out tactile language. Your question on preservation as a reason that materials are kept out of touch is spot on and also concerns archival digitization practices. Many contemporary 3D scanning techniques used by archives follow visual paradigms by scanning outlines of costumes for visual digital representations. My hope is that future preservation does not rely on visual preservation alone, so that we do not lose the rich haptic histories that artifacts can teach us about.

JF - By foregrounding vibration, temperature, resistance, and movement, the project shifts VR away from visual dominance. What kinds of new attentions or intimacies emerged through this multisensorial approach?

IP - During my residency, I took part in a seminar of DeafBlind poet John Lee Clark, who taught me that the goal is not to replace an existing sensory hierarchy with another, but to undo the idea of a hierarchy. Undoing visual dominance meant inviting sensory plurality. In the XR artwork Archive of Touch, the interplay of movement, vibration, resistance and sound creates an intimate experience of being in touch with archival objects. Touch is always relational: You cannot touch without also being touched. In Archive of Touch, every touch creates: sounds, vibrations, descriptions, visual textures. The archival materials from the Salzburg Festival Archive become alive – through our willingness and openness to be in touch with them.

JF - You describe play as fragile, tense, and prone to breakdown. How did failure, slowness, or malfunction become generative forces in the work?

IP - Imagine me in my studio, with vibration motors taped to my knees, fixing bugs on my computer and wishing for the sensations on my skin to finally feel like the silk of an opera dress! I love this question, as it reminds me of the frustrations of slowly and not always successfully working against the technical status quo of VR, as well as the joy of imagining and building controllers that work for many bodies and minds. In a way, this project started out with a failure: Of how commercial VR tech is failing disabled people. And this failure became generative. As the project continued, my prototypes of what a VR experience could feel like failed my disabled test players and me less, but it certainly failed at being what ‘smooth, well working tech’ is imagined as. I keep being very interested in moments of slowness, failure and play when it comes to access making with technology.

JF - Looking ahead, how might starting from crip knowledge and tactile imaginaries transform not just VR, but how we relate to cultural heritage more broadly?

IP - Starting from disabled tactile and remote access knowledges can transform how we think of and use technologies, and how these technologies can facilitate access to cultural heritage. When thinking of remote access, the brilliant work of disabled people at the height of the COVID pandemic comes to mind in sharing knowledges on how to connect online. This work has become part of cultural heritage itself in the form of the Critical Design Lab’s Remote Access Archive. DeafBlind communities use the term Virtual Touch to refer to the ways in which they stay in touch via email listservs. It is time to bring these knowledges in touch with how cultural heritage is commonly preserved and made (in)accessible. I think crip creativity can be a key to overcoming the oftentimes voiced concern that cultural heritage materials cannot be touched by a lot of people without being damaged. Disabled culture teaches us that there are many ways to touch and be in touch with each other and with cultural heritage, that we can hold vulnerability of people and materials together, and that after all, tactile access is something we can invent together, with and without tech.

Image Descriptions:

IzPaehr_Collage01: This collage shows touches across modalities: On the left, Iz hand is shown touching the opulent bodice of an opera dress. In the middle, Iz right arm reaches into the image and is holding a Quest Virtual Reality Controller. On the right, the dress from the left is shown in Virtual Reality.

IzPaehr_Collage02: This collage shows how the project experiments with Virtual Reality. On the left, a photo shows a custom controller that Iz is building with two of their hands holding vibration motors attached to cardboard pieces in place. On the right, a screenshot shows the costume of a tiger from the opera The Magic Flute in Virtual Reality. Half of the screenshot shows the virtual space, the other half blends into Iz living room and shows their arms holding Quest controllers.

IzPaehr_TactilePatches: A collage shows photos of prototypes of Iz’ alternative controllers. On the left photo, they are holding a controller made from 3D printed fabric into the camera, from which cables and a printed circuit board stick out. On the right, two photos show a soft controller worn on an arm. This controller is a soft 3D printed grid onto which stones are sewn.

ArchiveOfTouch_01: A collage shows the five opera costumes and props that can be felt in the Extended Reality installation Archive of Touch in different colors. In the front, there is an opulent opera dress from the opera Der Rosenkavalier, with two costumes behind it: A tiger, and Papageno from the opera Die Zauberflöte. A bicycle is visible in the back, as well as the costume of one of the ladies from Die Zauberflöte.

ArchiveOfTouch_02: Two costumes, one of the Magic Flute’s lady, and one of the Magic Flute’s tiger, look like ghostly presences on this screenshot from the Extended Reality artwork Archive of Touch. A text reads: In our „Look, Don’t Touch“ culture, Archive of Touch values disabled ways of knowing the world through touch.

ArchiveOfTouch_03: This collage shows three photos of Iz touching the original dress of the field marshall from the Salzburg Festival 1960ies edition of Der Rosenkavalier. On the left photo, Iz’ hand touches the bodice of the costume. The photo in the middle shows Iz lying on the floor and touching the trim of the costume with their face. The right photo shows fingers tracing the lace on the costume’s elbow.

ArchiveOfTouch_04: In this screenshot from the Extended Reality artwork Archive of Touch, two controllers of the Quest3 touch a horn that is part of the costume The Tiger. This costume originates from the opera The Magic Flute that was performed at the stage of Salzburg Festival in 1997. If you held the controllers in your hands, you would feel them vibrate while tracing the virtual costume.

Iz Paehr is an iterdisciplinary designer in love with disability access, internet infrastructure, and the subversive potential of play.

INTERVIEW WITH IZ PAEHR

JF - Feeling Virtual begins from lived practices of navigating an inaccessible world rather than retrofitting existing VR systems. How did starting from access reshape what virtual reality could become?

IP - My misfit experiences with VR started with the existing design of the controllers of commercially available VR systems, which are hand-held. Holding a walking stick at the same time makes it laborious to use two controllers at once. Here, my first access hack came in the form of a strap that I wrap around my shoulders and with which I can let the controllers dangle, while also moving with my mobility aid. aStarting from access meant asking questions to other disabled folks, slowing down and testing alternative setups together. I learned from my conversation partners that tactile knowledge is underappreciated in society as well as in technology design. This is why the project moved towards tactile access.

JF -Touch is usually removed from archival encounters in the name of preservation. What happened when you reintroduced touch as a way of knowing the Salzburg Festival Archive?

IP - I continue to be grateful that the team of the Salzburg Festival Archive facilitated my tactile access to their collections without hesitation. In the process of touching my way through opera and theatre history, I learned that sight is quite limited when it comes to knowing archival materials in detail. Often, touching a dress from the costume storage would reveal a hidden knot of embroidery yarn hidden underneath a corsage, or would make apparent that a diamond was made from plastic. I also realized how limited my own language was when trying to put these tactile experiences into words, an experience that resonates with the writings of blind scholars such as Lilian Korner. This is why one outcome of my project is a Tactile Descriptions Workbook that offers guiding questions and tactile sensing exercises to feel out tactile language. Your question on preservation as a reason that materials are kept out of touch is spot on and also concerns archival digitization practices. Many contemporary 3D scanning techniques used by archives follow visual paradigms by scanning outlines of costumes for visual digital representations. My hope is that future preservation does not rely on visual preservation alone, so that we do not lose the rich haptic histories that artifacts can teach us about.

JF - By foregrounding vibration, temperature, resistance, and movement, the project shifts VR away from visual dominance. What kinds of new attentions or intimacies emerged through this multisensorial approach?

IP - During my residency, I took part in a seminar of DeafBlind poet John Lee Clark, who taught me that the goal is not to replace an existing sensory hierarchy with another, but to undo the idea of a hierarchy. Undoing visual dominance meant inviting sensory plurality. In the XR artwork Archive of Touch, the interplay of movement, vibration, resistance and sound creates an intimate experience of being in touch with archival objects. Touch is always relational: You cannot touch without also being touched. In Archive of Touch, every touch creates: sounds, vibrations, descriptions, visual textures. The archival materials from the Salzburg Festival Archive become alive – through our willingness and openness to be in touch with them.

JF - You describe play as fragile, tense, and prone to breakdown. How did failure, slowness, or malfunction become generative forces in the work?

IP - Imagine me in my studio, with vibration motors taped to my knees, fixing bugs on my computer and wishing for the sensations on my skin to finally feel like the silk of an opera dress! I love this question, as it reminds me of the frustrations of slowly and not always successfully working against the technical status quo of VR, as well as the joy of imagining and building controllers that work for many bodies and minds. In a way, this project started out with a failure: Of how commercial VR tech is failing disabled people. And this failure became generative. As the project continued, my prototypes of what a VR experience could feel like failed my disabled test players and me less, but it certainly failed at being what ‘smooth, well working tech’ is imagined as. I keep being very interested in moments of slowness, failure and play when it comes to access making with technology.

JF - Looking ahead, how might starting from crip knowledge and tactile imaginaries transform not just VR, but how we relate to cultural heritage more broadly?

IP - Starting from disabled tactile and remote access knowledges can transform how we think of and use technologies, and how these technologies can facilitate access to cultural heritage. When thinking of remote access, the brilliant work of disabled people at the height of the COVID pandemic comes to mind in sharing knowledges on how to connect online. This work has become part of cultural heritage itself in the form of the Critical Design Lab’s Remote Access Archive. DeafBlind communities use the term Virtual Touch to refer to the ways in which they stay in touch via email listservs. It is time to bring these knowledges in touch with how cultural heritage is commonly preserved and made (in)accessible. I think crip creativity can be a key to overcoming the oftentimes voiced concern that cultural heritage materials cannot be touched by a lot of people without being damaged. Disabled culture teaches us that there are many ways to touch and be in touch with each other and with cultural heritage, that we can hold vulnerability of people and materials together, and that after all, tactile access is something we can invent together, with and without tech.

Image Descriptions:

IzPaehr_Collage01: This collage shows touches across modalities: On the left, Iz hand is shown touching the opulent bodice of an opera dress. In the middle, Iz right arm reaches into the image and is holding a Quest Virtual Reality Controller. On the right, the dress from the left is shown in Virtual Reality.

IzPaehr_Collage02: This collage shows how the project experiments with Virtual Reality. On the left, a photo shows a custom controller that Iz is building with two of their hands holding vibration motors attached to cardboard pieces in place. On the right, a screenshot shows the costume of a tiger from the opera The Magic Flute in Virtual Reality. Half of the screenshot shows the virtual space, the other half blends into Iz living room and shows their arms holding Quest controllers.

IzPaehr_TactilePatches: A collage shows photos of prototypes of Iz’ alternative controllers. On the left photo, they are holding a controller made from 3D printed fabric into the camera, from which cables and a printed circuit board stick out. On the right, two photos show a soft controller worn on an arm. This controller is a soft 3D printed grid onto which stones are sewn.

ArchiveOfTouch_01: A collage shows the five opera costumes and props that can be felt in the Extended Reality installation Archive of Touch in different colors. In the front, there is an opulent opera dress from the opera Der Rosenkavalier, with two costumes behind it: A tiger, and Papageno from the opera Die Zauberflöte. A bicycle is visible in the back, as well as the costume of one of the ladies from Die Zauberflöte.

ArchiveOfTouch_02: Two costumes, one of the Magic Flute’s lady, and one of the Magic Flute’s tiger, look like ghostly presences on this screenshot from the Extended Reality artwork Archive of Touch. A text reads: In our „Look, Don’t Touch“ culture, Archive of Touch values disabled ways of knowing the world through touch.

ArchiveOfTouch_03: This collage shows three photos of Iz touching the original dress of the field marshall from the Salzburg Festival 1960ies edition of Der Rosenkavalier. On the left photo, Iz’ hand touches the bodice of the costume. The photo in the middle shows Iz lying on the floor and touching the trim of the costume with their face. The right photo shows fingers tracing the lace on the costume’s elbow.

ArchiveOfTouch_04: In this screenshot from the Extended Reality artwork Archive of Touch, two controllers of the Quest3 touch a horn that is part of the costume The Tiger. This costume originates from the opera The Magic Flute that was performed at the stage of Salzburg Festival in 1997. If you held the controllers in your hands, you would feel them vibrate while tracing the virtual costume.

JF - Feeling Virtual begins from lived practices of navigating an inaccessible world rather than retrofitting existing VR systems. How did starting from access reshape what virtual reality could become?

IP - My misfit experiences with VR started with the existing design of the controllers of commercially available VR systems, which are hand-held. Holding a walking stick at the same time makes it laborious to use two controllers at once. Here, my first access hack came in the form of a strap that I wrap around my shoulders and with which I can let the controllers dangle, while also moving with my mobility aid. aStarting from access meant asking questions to other disabled folks, slowing down and testing alternative setups together. I learned from my conversation partners that tactile knowledge is underappreciated in society as well as in technology design. This is why the project moved towards tactile access.

JF -Touch is usually removed from archival encounters in the name of preservation. What happened when you reintroduced touch as a way of knowing the Salzburg Festival Archive?

IP - I continue to be grateful that the team of the Salzburg Festival Archive facilitated my tactile access to their collections without hesitation. In the process of touching my way through opera and theatre history, I learned that sight is quite limited when it comes to knowing archival materials in detail. Often, touching a dress from the costume storage would reveal a hidden knot of embroidery yarn hidden underneath a corsage, or would make apparent that a diamond was made from plastic. I also realized how limited my own language was when trying to put these tactile experiences into words, an experience that resonates with the writings of blind scholars such as Lilian Korner. This is why one outcome of my project is a Tactile Descriptions Workbook that offers guiding questions and tactile sensing exercises to feel out tactile language. Your question on preservation as a reason that materials are kept out of touch is spot on and also concerns archival digitization practices. Many contemporary 3D scanning techniques used by archives follow visual paradigms by scanning outlines of costumes for visual digital representations. My hope is that future preservation does not rely on visual preservation alone, so that we do not lose the rich haptic histories that artifacts can teach us about.

JF - By foregrounding vibration, temperature, resistance, and movement, the project shifts VR away from visual dominance. What kinds of new attentions or intimacies emerged through this multisensorial approach?

IP - During my residency, I took part in a seminar of DeafBlind poet John Lee Clark, who taught me that the goal is not to replace an existing sensory hierarchy with another, but to undo the idea of a hierarchy. Undoing visual dominance meant inviting sensory plurality. In the XR artwork Archive of Touch, the interplay of movement, vibration, resistance and sound creates an intimate experience of being in touch with archival objects. Touch is always relational: You cannot touch without also being touched. In Archive of Touch, every touch creates: sounds, vibrations, descriptions, visual textures. The archival materials from the Salzburg Festival Archive become alive – through our willingness and openness to be in touch with them.

JF - You describe play as fragile, tense, and prone to breakdown. How did failure, slowness, or malfunction become generative forces in the work?

IP - Imagine me in my studio, with vibration motors taped to my knees, fixing bugs on my computer and wishing for the sensations on my skin to finally feel like the silk of an opera dress! I love this question, as it reminds me of the frustrations of slowly and not always successfully working against the technical status quo of VR, as well as the joy of imagining and building controllers that work for many bodies and minds. In a way, this project started out with a failure: Of how commercial VR tech is failing disabled people. And this failure became generative. As the project continued, my prototypes of what a VR experience could feel like failed my disabled test players and me less, but it certainly failed at being what ‘smooth, well working tech’ is imagined as. I keep being very interested in moments of slowness, failure and play when it comes to access making with technology.

JF - Looking ahead, how might starting from crip knowledge and tactile imaginaries transform not just VR, but how we relate to cultural heritage more broadly?

IP - Starting from disabled tactile and remote access knowledges can transform how we think of and use technologies, and how these technologies can facilitate access to cultural heritage. When thinking of remote access, the brilliant work of disabled people at the height of the COVID pandemic comes to mind in sharing knowledges on how to connect online. This work has become part of cultural heritage itself in the form of the Critical Design Lab’s Remote Access Archive. DeafBlind communities use the term Virtual Touch to refer to the ways in which they stay in touch via email listservs. It is time to bring these knowledges in touch with how cultural heritage is commonly preserved and made (in)accessible. I think crip creativity can be a key to overcoming the oftentimes voiced concern that cultural heritage materials cannot be touched by a lot of people without being damaged. Disabled culture teaches us that there are many ways to touch and be in touch with each other and with cultural heritage, that we can hold vulnerability of people and materials together, and that after all, tactile access is something we can invent together, with and without tech.

Image Descriptions:

IzPaehr_Collage01: This collage shows touches across modalities: On the left, Iz hand is shown touching the opulent bodice of an opera dress. In the middle, Iz right arm reaches into the image and is holding a Quest Virtual Reality Controller. On the right, the dress from the left is shown in Virtual Reality.

IzPaehr_Collage02: This collage shows how the project experiments with Virtual Reality. On the left, a photo shows a custom controller that Iz is building with two of their hands holding vibration motors attached to cardboard pieces in place. On the right, a screenshot shows the costume of a tiger from the opera The Magic Flute in Virtual Reality. Half of the screenshot shows the virtual space, the other half blends into Iz living room and shows their arms holding Quest controllers.

IzPaehr_TactilePatches: A collage shows photos of prototypes of Iz’ alternative controllers. On the left photo, they are holding a controller made from 3D printed fabric into the camera, from which cables and a printed circuit board stick out. On the right, two photos show a soft controller worn on an arm. This controller is a soft 3D printed grid onto which stones are sewn.

ArchiveOfTouch_01: A collage shows the five opera costumes and props that can be felt in the Extended Reality installation Archive of Touch in different colors. In the front, there is an opulent opera dress from the opera Der Rosenkavalier, with two costumes behind it: A tiger, and Papageno from the opera Die Zauberflöte. A bicycle is visible in the back, as well as the costume of one of the ladies from Die Zauberflöte.

ArchiveOfTouch_02: Two costumes, one of the Magic Flute’s lady, and one of the Magic Flute’s tiger, look like ghostly presences on this screenshot from the Extended Reality artwork Archive of Touch. A text reads: In our „Look, Don’t Touch“ culture, Archive of Touch values disabled ways of knowing the world through touch.

ArchiveOfTouch_03: This collage shows three photos of Iz touching the original dress of the field marshall from the Salzburg Festival 1960ies edition of Der Rosenkavalier. On the left photo, Iz’ hand touches the bodice of the costume. The photo in the middle shows Iz lying on the floor and touching the trim of the costume with their face. The right photo shows fingers tracing the lace on the costume’s elbow.

ArchiveOfTouch_04: In this screenshot from the Extended Reality artwork Archive of Touch, two controllers of the Quest3 touch a horn that is part of the costume The Tiger. This costume originates from the opera The Magic Flute that was performed at the stage of Salzburg Festival in 1997. If you held the controllers in your hands, you would feel them vibrate while tracing the virtual costume.

Iz Paehr is an iterdisciplinary designer in love with disability access, internet infrastructure, and the subversive potential of play.